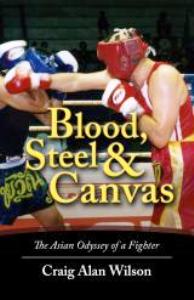

“Blood, Steel and Canvas: The Asian Odyssey of a Fighter” by Craig Alan Wilson (Diversion Books; $4.99) is a spare and enjoyable e-book that uses boxing as a celebration of life instead of using life as an excuse to box. It radiates with a light-hearted warmth that many books about our beloved sport lack.

Here are its major themes: disliking corporate law, relocating to the Philippines, learning to box, enduring a coup d’état, returning to Washington D.C., suffering colitis, surviving colon cancer, running a marathon, moving to Thailand, boxing in famous Thai venues, and becoming a father.

*

Much of this book’s best writing has nothing whatever to do with boxing, though. Its commentaries on Yale undergrad work, Harvard Law School and the clerkships and striving that follow set a refreshing pace.

The boxing writing, too, is often crisp and well-reported, and its treatments of the sport’s rudiments are graceful. You may already know what hand pads are, but Wilson’s presentation of them is still a pleasant surprise. And there’s no doubting his love for the sport.

But what delights most about this book is its author’s self-deprecation. Whether examining the discomforts of wearing an ileostomy pouch – effectively carrying one’s intestine externally – or being staggered by a superior while sparring, “Blood, Steel and Canvas” happily chides itself and its first-person narrator.

*

“Long stints in the library and my Type-A personality had propelled me to the pinnacle,” writes Wilson, “but as I labored into the night and on weekends, canceling dates and eating Chinese take-out dinners at my desk, I came to an eye-opening conclusion: success sucks.”

Deprived of a life around people from whom he could learn things worth knowing and wary of an expanding waistline, Wilson chose to begin his boxing adventure in the Philippines of all places. Boxing, for all its self-induced hardships, was better for him than at least one other discipline.

“The logical move, forswearing chocolate, I would not even contemplate,” Wilson writes, “so I resolved to lose weight by taking up exercise, a novel proposition that ultimately led me to the Elorde Sports Center.”

This boxing journey took Wilson from the Philippines back to Washington D.C. and ultimately to Thailand, where he still lives, and a gym that complemented his self-deprecating style.

“At first the Sot Chitrlada [gym] professionals treated me with kid gloves, but as the months went by and my zest for combat became apparent, they abandoned the Mr. Nice Guy approach and went full steam ahead,” he writes. “(I outweighed most of them by at least twenty pounds; otherwise this book would have been published posthumously.)”

*

Among Wilson’s well-explored subtler themes, its underlayers, is the nature of life as an ex-pat. He has plenty to contribute on this subject, and his observations are insightful ones. Of those American ex-pats who reside in Thailand but make no effort to learn its language, he writes:

“Not only is their refusal hypocritical, but it is counter-productive, as they miss out on one of the real joys of expatriate life, experiencing and being a part of the local culture.”

If “Blood, Steal and Canvas” has a weakness, though, it comes in an unexpected spot. While reporting or expounding, Wilson writes good sentences that, to borrow his term, “effervesce”; but when he switches to motivational-speaker mode, his prose takes on a salesy hue; he reaches in the self-help cereal box and pulls out toys that can feel clichéd:

“A cancer diagnosis does not mean that your life has hit a brick wall. Pardon the expression, but you have to roll with the punches.”

Wilson knows better than to do this and subsequently takes things into his “gloves” – instead of his hands – and occasionally precedes what he knows to be a cliché with a plea for pardon like the one above.

*

All is indeed pardonable because Wilson otherwise makes so many good choices throughout his book’s 121 pages.

“At the end, I held up my gloves and nodded to show that I wanted to continue,” he writes of his first knockout defeat. “The referee looked in my eyes and watched as I rocked on my feet. Putting his arm around me, he escorted me back to my corner. The bout was over. Secretly I did not mind.”

When in another boxing book have you read a last sentence honest as that one?

“Through boxing I gained self-confidence,” writes Wilson. “I discovered that I could take care of myself, not just in the sense of the adolescent’s ‘let’s settle this outside’ mentality, but – much more important – in the belated realization that I need not be scared of what others might think.”

And a fear of humiliation is undoubtedly one that haunts a fighter more than pain or injury.

*

There is another curious decision Wilson must have made, and it merits mention. A boxing book that dedicates most of its opening 1/3 to Manila never once makes itself about Manny Pacquiao. “Blood, Steel and Canvas” is its author’s memoir, and if Wilson didn’t meet Pacquiao while he was in Manila, he also didn’t meet boys who “had Pacquiao’s hunger” or “threw a left cross like Pacquiao” or any of the other Pacquiao-isms a marketing team would have added.

A choice like that deserves a comment like this: You will learn more about what made Pacquiao what he is today in the first 40 pages of Wilson’s book than in anything you read this November.

*

Through its author’s willingness to tread lightly with life’s most serious subjects – cancer, law, combat, failure and fatherhood – “Blood, Steel and Canvas” provides a quick and valuable experience.

“I am not a great lawyer,” concludes Wilson. “I have not enjoyed the professional renown and monetary rewards that have flowed to many of my classmates.”

Perhaps not. But by living an interesting life and writing a book about it, Wilson has done us a service.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry