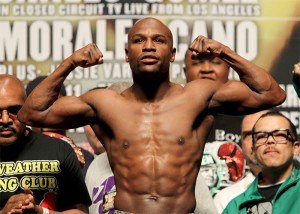

We are where we were 20 months ago. Floyd Mayweather knows he can beat Many Pacquiao, doesn’t understand why the rest of us don’t, and wants every detail just so before he’ll agree to do it. Pacquiao, when he thinks about boxing at all, fears Mayweather less than he feared a half-dozen previous opponents. Promoter Bob Arum wants no part of a Mayweather match. Boxing fans are polarized. Everyone else has moved on.

In frustrating and disillusioning moments such as these, it can be a valuable exercise to imagine the future, 30 years along, and ask yourself if any of this will truly matter.

If Mayweather and Pacquiao never fight, none of this will matter even a little. That’s worth remembering as you look back on two years of Mayweather and Pacquiao fights and imagine two more years of Mayweather and Pacquiao fights.

Probability says neither man will retire. Probability also says they will not fight each other. There will always be something. If the drug-test hurdle is surmounted, it will be a matter of what gloves to use. If there’s a treaty on the gloves, it will be a question of who enters the ring first. And all of this assumes – assumes ridiculously, by the way – that a revenue-sharing agreement could ever be reached between Mayweather Promotions, Top Rank and HBO.

HBO, after all, is more responsible for Mayweather’s ascension in pop culture than even Mayweather is. It has also put its weight behind making a Mayweather-Pacquiao fight before. Forget not: It was an HBO executive who told the MGM Grand media center immediately after 2009’s Pacquiao-Miguel Cotto fight that a Golden Boy Promotions rep had just called and promised negotiations with Top Rank to begin Monday. That was 23 months ago.

While the subject of HBO is up, let’s discuss the rousing finale of the HBO Mayweather-Victor Ortiz movie that premiered Saturday. Along with showing us Ortiz was two parts the guy exposed by Marcos Maidana and one part the monster Andre Berto built, episode 5 of “24/7” provided this: All-access passes make us dumber about boxing, not smarter.

When Mayweather announced he would fight Ortiz, every aficionado said it was easy work for Mayweather. Professional gamblers concurred. Then four, all-access episodes narrowed odds and made aficionados consider a way for Ortiz to win. Most of us didn’t do anything crazy as change our picks, but with the one noble exception of Thomas Hauser, we all wrote previews and watched to see if something unexpected might happen.

Alas, something unexpected and ultimately unsatisfying happens in every Mayweather fight, no? This time it was Mayweather’s exploitation of Ortiz’s fragile brain. Last time it was Mayweather’s exploitation of Shane Mosley’s eroded reflexes. Time before that, it was Mayweather’s exploitation of Juan Manuel Marquez’s slighter frame. There’s always some exploitation.

Mayweather fights are marketed at a very specific type of fan. When a Mayweather fight ends, this sort of guy immediately tells whoever is in earshot that Mayweather reminds him of that time he almost had to throw a beatdown on a guy at the mall. Then this guy goes back into hiding. He threatens to support Graterford Prison’s own Bernard Hopkins, of course, but pay-per-view receipts later prove that threat hollow.

The rest of our sport’s casual fans feel dissatisfied and sort of stupid. They punish what Mayweather did to them with a tool devastating as it is unnoticed: their indifference. That is how it happens, ultimately. It’s a thing Mayweather senses even if he does not know what to call it. But for the 30 minutes he spends in a boxing ring every 18 months, he does not exist in the collective mind of the American mass. It makes him loopy.

Like General George McClellan at the outbreak of Civil War hostilities, Mayweather wants to win his largest battle without having to fight it. He wants us to credit him with beating Pacquiao without he does it. You know what? Most aficionados do assume Mayweather would beat Pacquiao with something between ease and moderate difficulty, but we’ll be damned if we’re going to shout over Mayweather’s inane self-aggrandizement to tell him so.

If this time in boxing is not the Pacquiao Era, in other words, what is it? A mediocre stretch of lumbering European heavyweights and overpriced mismatches that compose either boxing’s final era or an eventually forgotten one. Mayweather is the king, as the saying goes, and boxing is nothing – and that makes Mayweather the king of nothing. If Mayweather never does fight Pacquiao, he won’t be remembered for not-fighting Pacquiao. He won’t be remembered at all.

Some day 30 years from now, some enterprising journalist may do a retrospective on the Greatest Fight that Never Was instead of, say, a feature on women’s figure skating, and what will he treat? Bob Arum will be long gone. Mayweather will be a broke trainer. Pacquiao will be the former president of the Philippines, a man history regards as a better prizefighter than national leader.

Under the poorly lighted staircase of a defunct gym, Mayweather will shout, “You know that I woulda beat that motherf—er!” Those of us still alive will nod and shrug and think about how little it mattered, finally. For a moment, we’ll remember what we were doing back then, remember it the way we remember our aunt’s wedding reception each time we hear Kool and the Gang’s “Celebration” play. And then all of life that has happened to us since will wash back over the moment, and it will be lost.

Mayweather makes veteran journalists wonder why they still bother. He makes young journalists wonder if they should continue bothering. No Mayweather victory is a victory for anyone but Mayweather. Figures like that do not live on as legends; they are either forgotten in time or become cautionary tales.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry