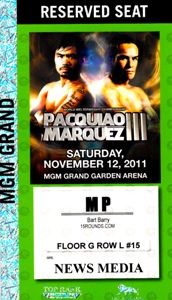

Portrait of a credential to 2011’s biggest fight, Part 1

The day Manny Pacquiao and Juan Manuel Marquez fought their rubber match in November 2011, Las Vegas was in recovery. The city tried to pull itself from the depressed conditions every cabbie was willing to describe during trips to McCarran Airport, in 2009 and 2010. Vegas’ new line was taxi traffic; record-setting or record-tying or something.

Pacquiao-Marquez III was about money and “Money.” The first governs everything in prizefighting, as the second, Floyd “Money” Mayweather, once explained to Shane Mosley. Pacquiao, always quick with his fist when signing contracts as punching, was a market unto himself, hawking defunct tablet computers, imported veggies and iTunes singles. And Pacquiao-Mayweather (whose promotion Pacquiao-Marquez III would help) would be the most important fight in a century or two when it happened.

The media was in a frenzy of Pacquiao celebration, spurred and lashed by promoter Bob Arum, for whom Pacquiao was the final masterpiece of a historic sales career.

The masterpiece underwent a withering inspection, though, and came out lusterless and resented.

Or so I remember it.

*

The day Manny Pacquiao and Juan Manuel Marquez fought their rubber match in November 2011, Las Vegas readied to host an event with the reflexive trickery it has patented: Big events go to Las Vegas because Las Vegas hosts only big events.

With the world economy still receding, prizefighting watched its pay-per-view receipts plummet. There were two or three major events every year that yielded considerably less revenue than the 10 smaller events that happened five years before. It meant even the sport’s two biggest promotional outfits were now humbled in their wares if not their oratory.

Pacquiao would blow through Marquez, the older, smaller, slower opponent whom he’d already officially beaten and drawn with, and after stopping Marquez violently and abruptly – something Money May did not do while dominating Marquez in 2009 – Pacquiao would redeem the sport and his handlers’ coffers, with The Fight to Save Boxing, then approaching its third year of marination.

The print media picked Pacquiao overwhelmingly enough to wonder not if Marquez could win or even remain conscious but if Marquez could escape Pacquiao’s ferocity with any remnants of his health intact. And by night’s end, when the ring announcer read “and still champion!” and Pacquiao raised his hands, we all felt a little sheepish and disgusted.

*

The day Manny Pacquiao and Juan Manuel Marquez fought their rubber match in November 2011, Las Vegas said it was coming back, of course, but was it really? Strolls through the basement mall of MGM Grand substantiated none of the rosy reports one heard in the restaurants above.

There were dark tones beneath the rubber match, and they began to glow. Manny Pacquiao, accused of using performance-enhancing drugs, agreed unconditionally to prefight testing if Money May demanded it for their match, the one to come after Pacquiao blew through Marquez. Or Pacquiao didn’t agree. No one was clear about this. The facts changed hourly. Obfuscating insiders fed reports to websites that copied, pasted and published anything emailed their way. Then Juan Manuel Marquez revealed a theretofore-concealed sense of irony and hired a former PED distributor as his strength coach. And he sure wasn’t smaller when he hit the scale at the weigh-in, that tired prefight event used to promote the next day’s match to those unable to afford a pre-sold/post-scalped ticket for Saturday. There, the only memorable thing was a line from a fellow scribe who treated the week’s PED controversy and concluded: “Hell, they’re all probably on something, so I say, ‘Smoke’em if you got’em!’”

So many questions. How would Pacquiao fare against Mayweather when they fought after Pacquiao ruined Marquez? Would Mayweather, frightened by the way Pacquiao blitzed Marquez, find a new reason not to make the fight? Would Pacquiao retire from boxing before becoming president of the Philippines?

And then in the hour after the fight: Did any knowledgeable spectator still think Pacquiao could win more than a round against Money May, if The Fight that Might Have Saved Boxing ever did happen?

Thanks a bunch, Juan Manuel.

*

The day Manny Pacquiao and Juan Manuel Marquez fought their rubber match in November 2011, Las Vegas felt a little tired. Such straining had been done so hopelessly for so many months, a churning through so many new valets and carving-station chefs. Was it still any use?

Pacquiao approached his third fight with an unusual savageness. He wanted to stop Marquez and all the witless banter about Marquez winning one if not both of their previous matches. Pacquiao went to work on the handpads and heavybags at Freddie Roach’s Wild Card Boxing Club in a way that left Roach and others taken aback. This one was personal for Manny.

Many kilometers south, in Mexico City, Marquez mostly did what he always did. It was a system that worked fine. His trainer, Nacho Beristain, prophesied that this new, refined Pacquiao, this two-handed puncher with improved footwork and a right hook perilous as his left cross, was, if anything, an easier mark for Marquez – for being predictable. If Beristain was fearful, or even aware, of the ferociousness Pacquiao planned for his charge, Beristain did an excellent imitation of a trainer who was not.

In round 6 of their third match, Marquez began to undress Pacquiao before a full MGM Grand Garden Arena. He revealed the masterful job Pacquiao’s promoter had done of building the Pacquiao brand against increasingly bigger and more shop-worn opponents. Pacquiao had seen no one with Marquez’s understanding of another man in combat since the last time he fought Marquez. That was no accident. Making a third fight with Marquez sure as hell was.

We were assembled at our press tables to help lift Pacquiao-Mayweather from longshot to inevitability in the days after Pacquiao leveled Marquez. But after what Marquez did to Pacquiao, we quietly awaited justice, however unpalatable. When the 116-112 scorecard came in, we accepted Marquez’s victory and spent five or so seconds plotting our sport’s next step.

When “and still champion” followed the 116-112 scorecard, most of us shook our heads, and the rest muttered “bullshit.”

***

Editor’s note: Part 2 will be published on Jan. 2.