The moment Mexican Juan Manuel Marquez took Filipino Manny Pacquiao’s consciousness with a right cross on Dec. 8 brought a series of instants affecting as can be experienced in professional sport. One of those instants brought a deep, royal blue sense of Marquez’s vindication, reminiscent in its way of Antonio Margarito’s victory over Miguel Cotto at MGM Grand in 2008. Reminiscent, conjecture says, in a few ways.

There was a difference between the two moments, though, a difference uncaptured by television, that boasting, refracting medium that lies to congregants flatteringly enough they later find no irony in remanding events’ eyewitnesses to tapes of what television told them to see. Television, that extraordinary phenomenon, continues to affect boxing more than it covers it.

The difference between Marquez and Margarito lay in their reactions. Margarito, who had longer to process Cotto’s demise, was euphoric, dropping to his knees, blessing himself, spinning joyfully in his cornermen’s arms. Marquez was not surprised as anyone else. He’d the benefit of feeling the punch on his right knuckle, of course, but it was not entirely that. He was not containing a euphoria as he paced with his black gloves on the red waistband of his trunks, inching nearer Pacquiao to admire what he’d done, or when he ran across the ring – to a neutral corner, mind you – and mounted a turnbuckle to savor his vindication; he was acting out a conqueror’s script.

What happened on television was a single camera that showed Pacquiao regaining consciousness sooner than what happened at ringside, where split screens above the ring showed Marquez fixated on a proper celebration, ensuring his white Rexona sponsor’s cap was straightened, while Pacquiao’s wife sobbed, silently screamed and tried to swim to her facedown husband, promoter Bob Arum consoling her while looking inconsolable. It happened much slower at ringside; there was no one shouting about keystones or anticipating fifth fights: there was confusion marinated in fright, tempered by a need to record what transpired.

But memory is a funny thing, and what I remember best from those moments is Marquez’s unflinching seizure of them, while the Filipino journalist on my right worried Pacquiao might never stir. It was a confirmation of this: Were Marquez offered a choice in the last moment of the sixth round, told if he threw that right hand it might kill Pacquiao but if he didn’t he might lose another close decision, Marquez would throw the punch. Whatever other prizefighters tell you about themselves during promotions, know this: A willingness to kill in the ring makes Marquez unique.

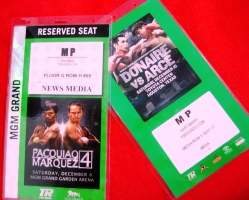

Six days later in Houston, the mood was much lighter. It was the weighin for an inconsequential coronation: a crowning of Filipino Nonito Donaire as 2012’s fighter of the year, and a crowning payday for Mexican Jorge Arce. Donaire was a safer athlete to cover than Marquez.

Arce did some chemical experimentation in camp to make his upper body more muscular, in the laboratory of Marquez’s own scientist, but at worse, one suspected, the enhanced physique might extend Arce’s consciousness a round. The left hook Donaire doused Arce’s spirit with at Toyota Center was comparatively merciful. Arce went down, but there was little fright, as one sensed Donaire would drop on his knees and administer CPR if his friend were in genuine peril.

Somehow, strangely, illogically, knowing a man rendered another unconscious in an act of temporarily suspended affection, as Donaire did Arce, made it feel safer than what congealed indifference Marquez showed Pacquiao’s plight in Las Vegas.

*

The moment Mexican Juan Manuel Marquez took Filipino Manny Pacquiao’s consciousness with a right cross on Dec. 8 made their tetralogy a unique event in boxing history. In its asymmetry – Pacquiao dropped Marquez five times but will be remembered as the rivalry’s collapsed form on the blue mat – and its excellence, it entered our sport’s annals as something that may be approached or someday bettered but never matched: a rivalry whose first three fights were excellent enough to merit a fourth but inferior to the fourth.

What happened in the seven days that began Dec. 8th was unique and excellent, too, in this way: The fight of the year and the fighter of the year happened in a week together but 1,500 miles apart. Marquez-Pacquiao IV will be remembered as 2012’s best fight because of its superior composition of three elements, violence and craft and consequence – the winner was covered in his own blood when he made his opponent sleep with the same counter right hand he landed the round before, spinning Pacquiao sideways in the fifth, and with that right hand in round 6 Marquez brought the conclusion of an era.

Nonito Donaire will be declared 2012’s best prizefighter because of a superior composition of these three elements: Activity, craft and consequence. Donaire fought twice as often as his peers, and he fought actual opponents in actual weight classes, gaming none of them with the scale, and by subjecting himself to VADA testing he put the lie to most athletes’ claims and exerted pressure on everyone including his own team.

*

The moment Mexican Juan Manuel Marquez took Filipino Manny Pacquiao’s consciousness with a right cross on Dec. 8, Marquez had been the slower man in the fourth fight as he’d been in the first and second and third. He was able to offset Pacquiao’s unique attack with “inteligencia” – a word Marquez uttered in every interview he conducted after their second fight before their third after their third and before their fourth.

Marquez and his trainer Nacho Beristain welcomed the more conventional Pacquiao they saw in fight three; so long as Pacquiao’s punches came from familiar angles, no matter their speed or forcefulness, Marquez and Beristain did not fear them for the same reason a major league hitter does not fear a 120-mph fastball twice thrown over the plate at belt level. One doesn’t get in the major leagues without being able to hit a fastball, no matter its velocity, and one doesn’t get out of a Mexico City gym without being able to sustain any punch he sees coming.

The scariest moment of Dec. 8, then, was not the Pacquiao left hand that knocked Marquez onto the knuckles of his left glove but instead the crazily executed, left-foot-off-the-mat, right-hand chop Pacquiao landed a few seconds after he put Marquez on the canvas. That was the punch that stiffened Marquez’s right leg and sent him in frantic retreat till the ropes’ touching his back made him swing at Pacquiao savagely because that is what Marquez does when cornered.

After the fight there was an odd little moment when Marquez and Beristain, no sore winners they, alternately led the MGM Grand media center in a rendition of “Happy Birthday” for Bob Arum and a heartfelt hug for the elderly promoter and rival whom Beristain flatly accused of ruining the sport while they shared a Mandalay Bay dais after Pacquiao-Marquez II in 2008.

Arum’s appearance, six days later, at a Houston mall, where he briefly posed for pictures with Donaire and Arce, was perfunctory – like everyone else’s.

***

Editor’s note: Part 2 will be posted Wednesday.

***

Bart Barry can be reached at bart.barrys.email (at) gmail.com