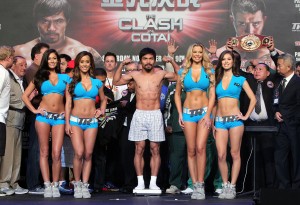

There’s terrible irony in news that the Philippines has frozen Manny Pacquiao’s financial assets and placed a lien on the Filipino Congressman’s home over allegations that he owes $50.2 million in unpaid taxes. Pacquiao fought Brandon Rios in China to avoid U.S. taxes, yet he finds himself in a tax fight at home just a few days after a convincing decision over Rios in Macao.

There’s been a lot of talk about whom Pacquiao will fight next. Juan Manuel Marquez, Timothy Bradley and Ruslan Provodnikov have all been mentioned. No matter where and when the next one happens, however, the taxman could be there in what might be Pacquiao’s toughest and longest fight.

The Filipino Bureau of Internal Revenue’s claim against him is as confusing as the IRS long form. In a prepared statement, Pacquiao promoter Bob Arum said U.S. taxes have been paid for five fights during the two years in question, 2008 and 2009. Under Filipino law, Pacquiao would not be have to pay the Filipino taxes on money already taxed and paid in the U.S., Even there, however, a potential problem has emerged. The U.S. tax rate in 2008 and 2009 was 30 percent. The Filipino rate was 32 percent. In some news reports, Filipino authorities have suggested that Pacquiao might be liable for the two-percent difference.

Arum said that Top Rank will prove that Pacquiao paid his U.S. taxes. Documentation, certified by the IRS, will be made available, Arum said. But you might get on to the Obamacare website before those documents get done. Filipino tax commissioner Kim Henares said she has been waiting for them for two years. Expect this mess to drag on. And on.

Meanwhile, Pacquiao has alleged harassment. Maybe. He’s a politician, after all. Alleging tax evasion has always been one way to attack a political opponent, in the U.S. and everywhere else. If the political version of a low blow is in the mix, however, it only makes things messier than they already appear to be. It also means it will be there, in one form or another, for as long as Pacquiao stays in politics

Politics and money, often inseparable, have become the two-headed distraction that the multi-tasking Pacquaio cannot control. Against Rios, Pacquaio showed he still can fight at a level that can generate more money in a career already estimated to have grossed $300 million. He looks to have a couple of years, three or four more fights, left in the bank. In a somewhat surprising announcement, Arum said Pacquiao will be back in the U.S. for a fight in April.

There had been talk that Pacquiao would never set foot in a U.S. ring again because of President Barack Obama’s 39.6-percent tax rate. Even with that, however, the U.S. still might be the best place to maximize Pacquiao’s income because the pay-per-view infrastructure is in place. In China, it’s not and won’t be for perhaps another year. Pacquiao can’t wait and HBO won’t. In Macao, Pacquiao’s guarantee was $17 million. The guess is that he’ll wind up with about $20 million after he gets his cut of the pay-per-view, still undisclosed. If those projections stand up and the Filipino tax man takes 32 percent, Pacquiao winds up with $13.6 million.

In his loss by a lethal stoppage to Juan Manuel Marquez last December in Las Vegas, Pacquiao grossed about $30 million. At the old IRS rate of 30 percent, he netted $21 million. Under the new rate of 39.6 percent, his net would have been $18.12 million, or $4.52 million more than he was projected to collect in Macao. Follow the money. Arum always does. His Chinese venture looks to be an investment in the future. In time, maybe the money will be there. For now, however, it’s where it’s always been.

At 34, money is probably more important than ever for Pacquiao. He has just a more few opportunities to make the big bucks. Although confusing, the Filipino tax claim only adds a sense of urgency to the final stage in his career. In part, the tax controversy isn’t exactly a surprise. There has been anecdotal evidence for at least year that Pacquiao is under some financial pressure. There have always been stories about Pacquiao’s generosity. Arum openly joked about it. Then, worried about it.

Pacquiao gave it away to poor people on Filipino streets. Then, he spent lavishly on political campaigns for himself and wife Jinkee. In August 2013, he put his Los Angeles home up for sale at $2.7 million. A longtime associate, Wakee Salud, was quoted in Filipino media as saying that Pacquiao was going broke. For now, it’s impossible to know if he is. Or he isn’t. But the tax controversy is a sign that money will motivate him as much as it does Floyd Mayweather Jr., who has the “Money” nickname and more of it than anybody.

Maybe, money will finally make the Mayweather-Pacquiao showdown. Don’t bet on it. But if it ever does, don’t be surprised if the Filipino taxman is there, demanding most, if not all, of Pacquiao’ share in what could be $100-million fight.