By Bart Barry-

LAS VEGAS – Having scored the first match between American Timothy Bradley and Filipino Manny Pacquiao the wrong way from ringside, I found myself situated in a spot from which scoring was impossible at the rematch. With the back wall as my headrest, peering at the ring from a seat meters above the ceiling camera and a full level above a concourse kiosk advertising binocular rentals, I saw Pacquiao and Bradley approximate the choreography of modern dance, which approximates the behavior of molecules in an excited state: colliding, racing apart, reversing course, colliding again, racing apart.

Pacquiao won a fair and unanimous decision at MGM Grand Garden Arena, Saturday, in a match more competitive than great, a balletic sort of confrontation that required a 12th round headbutt to make either guy’s face look as a prizefighter’s should. Neither guy landed cleanly a fraction his power punches, and the match was marked more by hollowed-out suspense than building drama.

Manny Pacquiao and Timothy Bradley fought like grade-A natural athletes, tested and stamped Certified. For the first time in years, a spectator could watch a championship prizefight and assume from the data his eyes sent him, instead of what haranguing an agency or promoter or reporter did him, the two men making combat were not using performance-enhancing drugs. They appeared slow, inaccurate and generally winded much of the night. Gone was the Filipino wildcat who haunted trainer Nacho Beristain’s preparatory ruminations, and likely still haunts Erik Morales’ conscious thoughts. In his stead was a comparatively docile veteran who didn’t miss openings presented him when he went for them, and generally did not go for them.

Round 2 was the best Pacquiao and Bradley had made in their first 42 minutes of trying and better than anything they made in their next half hour. It was final evidence Pacquiao no longer has a three-minute round in him and evidence, too, that for whatever reason – and overtraining cannot be ruled out – Timothy Bradley cannot go a hard 36 minutes either; Bradley’s strategy was about conditioning, all about making Pacquiao fight more frantically than he wanted to, tossing punches at a pace unfamiliar to any version of Pacquiao over 130 pounds. It was the very thing, too, and Bradley sensed it and went for it, bringing what he once called “the dog” out, snarling and nipping, never imperiling exactly, but leveraging punches with his all body to make the other guy wilt.

If Pacquiao did not wilt, in rounds 3 and 4 he did wonder why the hell he had to keep doing this violent thing, and why he’ll have to do it for the foreseeable future, and where his fortune went. That happened after Pacquiao finally found Bradley in round 2 with his signature jab-feint-jab-cross combination, the one with which he felled everyone from Marco Antonio Barrera to Juan Manuel Marquez, and multiple times each, too, and Bradley did what everyone will now do in retaliation: Set his weight on his back foot and wing his right hand in a baseball pitcher’s homage to Marquez. The punch didn’t land, not till the fourth, but it made Pacquiao stop and ponder things in a way he never did in his prime.

The gambit worked too well for Bradley, and for the next seven or so minutes he threw his right hand with an enthusiasm so reckless it surely was a missed right in round 4, or early in round 5, that caused his calf muscle to sever and lump beneath him. Afterwards Bradley insisted his plunged activity level was not a matter of conditioning, and that is at least partially believable – although one must imagine how it saps a man’s stamina and fighting spirit to have to stop punches that hit only air. Stopping one’s own punches, after all, is a contingency for which no man trains; to replicate its effect, a trainer would have to yank a heavy bag entirely out his charge’s way on the final punch of each combination.

It took Pacquiao about six minutes – or 5:30 longer than it once might have – to realize Bradley was diminished. Pacquiao may not have thrown a punch in the opening minute of round 6. Round 11 brought justifiable boos from a slightly exasperated MGM Grand crowd, an acknowledgement Bradley no longer had the wherewithal to make a fight with Pacquiao, and Pacquiao was evidently scoring rounds in his head, locking in early leads and protecting them from a guy uninterested in taking them away.

The 12th was a competitive stanza between two good guys who like one another and like competing and really like the paychecks pay-per-view matches bring them but do not see any particular reason to endanger others unnecessarily. Each threw hard punches and hoped for a knockout, but finally it was a relenting sort of Timothy Bradley that Devon Alexander would have appreciated greatly, and a kindhearted sort of Manny Pacquiao that Erik Morales would have treated terribly. That brought a postfight scene long on words like “competitive” and short on words like “great” because, frankly, nobody believed Saturday’s match determined the world’s best welterweight.

As everyone at MGM Grand got reminded constantly all week, the world’s best welterweight is Floyd Mayweather, and he has a shrine window in the front entrance of MGM Grand to prove it. Mayweather’s countenance was ubiquitous during Pacquiao fight week – as promoter Bob Arum reminded everyone, in a show of indefatigability his main-event fighters could not emulate – and that is more than partially attributable to the casino’s sorrowful financial state; walking round and looking for postfight dining, one suspected that for a nominal fee the casino would have hung “Steve Wynn Wants You” posters with the hometown entrepreneur, and MGM competitor, pointing his finger in top-hat and tails.

Mayweather’s group took advantage of MGM’s finances in a move that was tacky, sure. But then, what in Vegas isn’t?

*

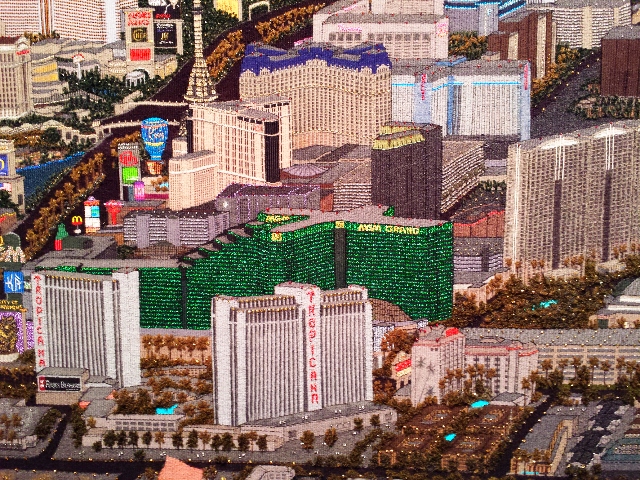

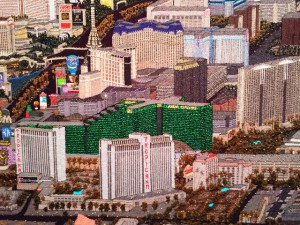

Editor’s note: The photo above is part of an extraordinary tapestry sewn by the Canadian artist Sola Fiedler and exhibited at Trifecta Gallery in the 18b Las Vegas Arts District.

*

Bart Barry can be reached at bart.barrys.email (at) gmail.com