By Bart Barry–

What if Michael Jordan came back tomorrow, at age 51, and won an NBA championship with, say, the Washington Wizards for whom he last played in 2003? It would be a massive event, an orgy of media celebration as one of the world’s most famous athletes, nay, men, returned to a field of glory and dominated at an age that was absurd. But once the orgy got tired and broke up and media folk went their separate ways, showing the promiscuity of spirit for which they are notorious, what would it say about professional basketball that a man in his sixth decade was able to dominate the best professionals in their 20s?

Now imagine for a second that Jordan never did retire in 2003 but rather finagled from that lousy Wizards team a four-corners offense, and as part of an ownership group selected referees prone to ignoring the shot clock, and won his 2014 championship in five games by an average score of 38-36. Would kids still wish to “Be like Mike” or would they perhaps decide football players were cooler, and spend a generation in cleats instead of Jordans?

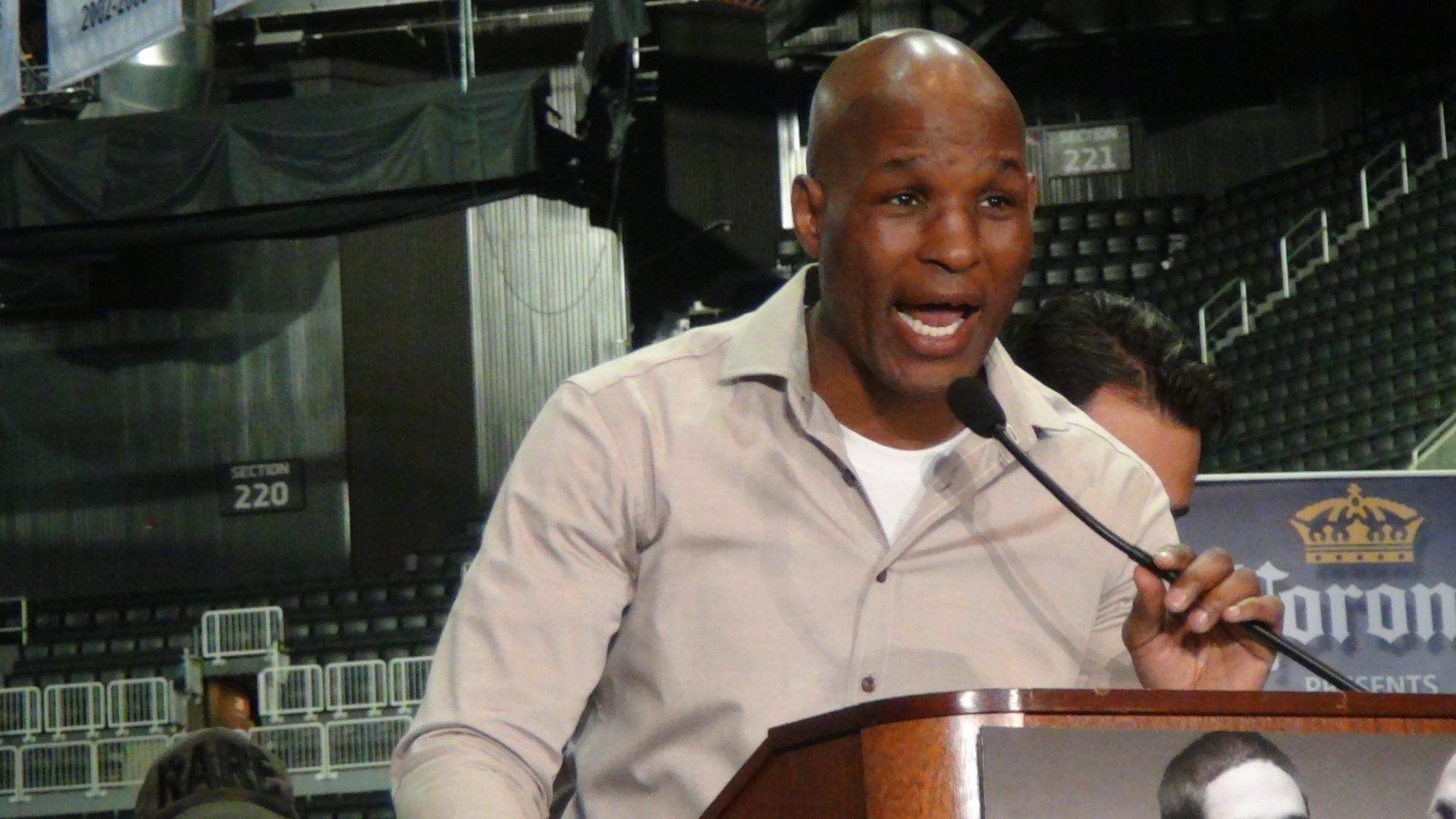

Saturday in Washington D.C., 49-year-old American Bernard “The Alien” Hopkins decisioned 30-year-old Kazakhstani light heavyweight titlist Beibut Shumenov in a match uncompetitive enough to bring heaps of dudgeon upon the lone judge who narrowly scored the match for Shumenov – in a nod to this fact much as another: Boxing aficionados are a cantankerous lot, and they like writers who tickle their lesser impulses, and also because tributes to agelessness are, almost invariably, insipid.

Through three rounds Saturday’s match was unwatchable as any Hopkins fight. Whatever else Shumenov was in his title-winning San Antonio match in December, and he was not particularly active, he was fearless. He had a willingness to stand wherever his opponent’s punches were bound to land, arms spread, chest bared in willing reception, and blast his way through them. Shumenov was not a picture of athleticism or class, perhaps, but he was verily a picture of self-belief. Hopkins removed that from him almost instantly and instead of seeing the dangerous puncher Texans watched flatten Tamas Kovacs, a man whose 23-0 dossier was, in retrospect, filled with hot air enough to fuel at least two questions of a Hopkins interview, fans in Washington D.C. got treated to an entirely untested man who did not belong near even a WBA light heavyweight title of the Eastern Bloc, much less the world.

Hopkins’ style remains defensively flawless – he has righted what balance issues sprung up years back against men of faster reflex and activity, and his skills as a handicapper, too, have kept pace, ensuring nobody busy or quick need apply for the privilege of standing across from him. Hopkins still flashes a silent dissent that takes men’s fingers off their triggers, and make no mistake about this either: Hopkins still punches hard and accurately enough to dissuade even men previously mistaken for portraits of fearlessness.

Boxing is not a dying sport in the sense of an entity that has a terminal condition – as anyone who reads about our sport knows already. Most arguments for boxing’s health treat either this certainty, that the spectacle of men swapping blows in a primal reenactment of what was done for finite resources millennia ago will not cease in our lifetimes and draw always paying spectators, or else fetishize the iota of one percent of licensed prizefighters still making massive fortunes from duping the public semiannually with large promotional budgets, special effects, roadtours, conference calls and a medium, television, ever compelled by itself to sell its customers reheated products they’ve already purchased.

It’s all missing widely a point quieter debate fails rarely to unearth: Ours is a sport fantastically diminished. Every number, from subscribers to media-day galas to earnings to punch stats, is open to wildeyed interpretation or misunderstanding in the name of profit, in the short-term or long-. What cannot be faked but easily confirmed in the urban area of any city in the United States, though, is this: There is a fraction the interest in boxing among kids today as there was even a generation ago. The gyms are not filling the way they always did before, and if your city is blessed with a full gym here or there, you can be assured your city once hosted five more than it does right now. Every local initiative to get kids in boxing begins with a wealthy donor and an employed politician and so much hope, and every local initiative quietly loses its impetus for one reason or another and is forgotten.

There is a desire among many to conflate probability and possibility, and so now is the time we excavate a gym here or there in an urban area that hasn’t hosted a fight and hasn’t a commission to confirm it, hold that concept aloft and give fullthroat to it as if its unverified existence disproves the very thing we all know already. And those that stick around to hear this conflation get convinced anew, inevitably, but their number dwindles each time.

Bernard Hopkins’ longevity and wondrous agelessness is good a monument as any to this. Were Michael Jordan still able to ply his Washington Wizards craftsmanship and win titles, outclassing LeBron James and friends in championship games, the NBA would know there was something dreadfully wrong with its product, would know how embarrassingly it appeared to those just discovering the physics of its nature, cylinders and shots and nets and reflexes and vertical leaps and the like, and would know better than to project images of half-filled arenas on the public’s consciousness as if all were just wonderful.

No, there will never be another Bernard Hopkins.

Bart Barry can be reached via bart.barrys.email (at) gmail.com