By Bart Barry–

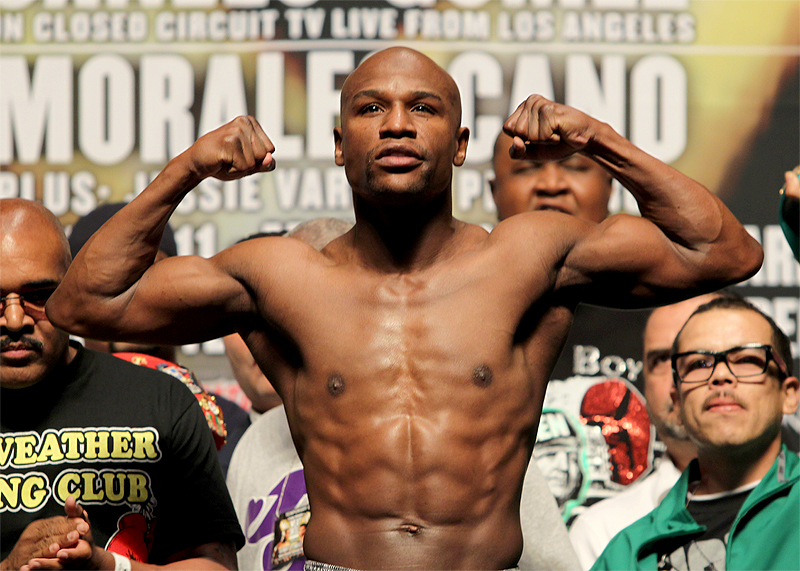

Saturday American Floyd “Money” Mayweather will fight once more at MGM Grand, this time with Argentine Marcos “El Chino” Maidana, in a welterweight title match the prestigious WBA has honored with “Super World” status, defying courageously those haters who argued for its belt to bear an “Average World” or “Lopsided World” appellation. Mayweather, who doesn’t care what anyone thinks, probably wouldn’t have paid their fees for anything less than a shot at “Super World” supremacy. How serendipitous.

If a Buddhist monk who spends his days meditating in a burlap coverall tells you he doesn’t care what others think, you might believe him. But if ever a man who spends tens of millions of dollars on conspicuous displays of his wealth tells you he doesn’t, check your wallet. Recently Robin Leach came out of retirement – surely he doesn’t need the money, because everyone who comes out of retirement never needs the money, just a rekindled love of the game – to walk us through the Big Boy Mansion in the 15th or so vacuous homage to Floyd Mayweather’s residence, showing us the million-dollar automobiles Mayweather drives alternately to a boxing gym and fastfood eatery, and the bedizened jewels Mayweather wears over white t-shirts.

It was another tired move from a tired franchise in a tired sport. Most of the off-television coverage of Saturday’s match has treated the prohibitive ratio oddsmakers assign the fight, declaring in a short declarative sentence not unlike that last one that Marcos Maidana hasn’t a jot of a chance of beating Floyd Mayweather. Those guys know their craft, and they understand probability better than Mayweather’s companions do, and they see no reason Maidana should beat Mayweather, and they are correct, there really isn’t a reason to expect anything that resembles a competitive main event Saturday. If you’re reading this, though, you’re part of the reliable half-million or so Americans our industry needs to buy every fight, and for your loyalty you deserve some reason to watch better than what pap Showtime infomercials offer.

Floyd Mayweather has to be in control of everything to be comfortable. Raised in what might euphemistically be called an unstable household, Mayweather imposes order wherever he can and does not relinquish it. He is perhaps the greatest handicapper of opponents boxing has ever seen, never endangering himself in a real fight against a real opponent when it can possibly be avoided. If Mayweather did not know about Antonio Margarito’s propensity for liberal hand-wrapping techniques in 2006, Mayweather absolutely knew something was off about him and wanted no part of a guy who was that big, somehow made 147 pounds for a few minutes of every year, and was incapable of discouragement.

Mayweather got the hell out of his contract with promoter Top Rank, in retrospect the best business decision made by a boxer in a generation, and fought Margarito’s wornout sparring partner Carlos Baldomir instead, because the Argentine surprised everyone and beat Zab Judah, three months before Mayweather did (don’t ask), and then changed his name to “Money” from “Pretty Boy” – a somewhat lamentable choice, as Mayweather has more beauty in person than cameras credit him, and money is, well, an idea so mundane it’s what every American dad spends 40 weekly hours making.

When he’s on, “Chino” Maidana does an excellent imitation of a fighter who is not in control. His footwork is a jumbled mess, his right hand is more like a club than a piston, his left hand is thrown with many times more commitment than technique, and his defense is poor enough that, after 38 prizefights and many more amateur bouts, his dad felt compelled to interrupt a televised barbecue and tell Chino to employ head movement. Odds are, that’s not the way to beat Mayweather – odds are, once more, pronouncedly that way. But in about the only reasonably unfiltered answer Mayweather gave his conference-call audience last week, “Money” did mention Emanuel Burton-Augustus as his toughest opponent, and Burton/Augustus was an old-time opponent who understood the value of dropping a competitive fight to a hometown favorite, quite often a more lucrative way to make a living than Maidana’s approach of whupping someone like Victor Ortiz in Staples Center, and imagine for a second the skill it takes to travel the country losing competitive fights without imperiling yourself unnecessarily. It also takes a lad who’s a bit off-kilter, and Burton-Augustus was surely that.

Maidana’s style was not built to solve the Mayweather style – Maidana’s style was built only to pulverize whatever object, animate or otherwise, came in its way – but it might have the ancillary effect of discomfiting Mayweather enough to make him entertain us for a brief respite, at least entertain us more than the aggregate of Mayweather’s last two opponents, Ghostly Canelo, managed to do. When I asked Paulie Malignaggi a few months ago how you fight a guy like Maidana, Malignaggi said you do nothing you didn’t learn in your first six months in a boxing gym. You go back to basics till you’re boring yourself.

Mayweather knows to do this; unlike the impostor buffoon Maidana traumatized in December, Mayweather comes right out of his cutiepie defense the second he’s touched for real. In their 2010 match, Shane Mosley dropped a right hand on Mayweather that made Money’s knees clap, and what did Mayweather do next? He set his hands high, went forward behind his jab, and applied pressure, like they teach on your first day in a gym.

Mayweather has much better footwork than the men whom Maidana has beaten up, and he’s physically stronger, too. He knows Maidana can be discouraged, and he will locate, before the bell sounds for round 4, the guy who dropped every minute to a 147-pound Devon Alexander and barely outboxed at 140 an unretired version of Erik Morales knocked-out twice by Manny Pacquiao five years earlier at super featherweight.

As ever, if this fight goes nine minutes without Mayweather being hurt badly, it will not be competitive. I’ll take Mayweather, UD-12, then, and hope for the sake of this increasingly moribund sport and its committed fans to be entirely wrong.

Bart Barry can be reached at bart.barrys.email (at) gmail.com