By Bart Barry-

SAN ANTONIO – This city’s largest art museum, SAMA, is now in the throes of a three-month exhibition, “Matisse: Life in Color,” that is exceptional by any museum’s standard of quality and particularly exceptional by this one’s. Frenchman Henri Matisse, a painter and sculptor and printmaker and papercutter and architect who resides in the top five of any critic’s pound-for-pound list of 20th-century artists, as a metaphor has nary a tangential relationship with anything to happen in boxing since June.

Not that he needs another recommendation.

If a distinction might be drawn between Matisse and those who run our beloved sport, and one will need be drawn if any of what follows is to happen, it is this: The more expert one is at visual arts generally and painting specifically, the more impressive Matisse becomes; while the more one learns about boxing today, the less impressed he is by those who do it, manage it, promote it, broadcast it and write about it.

There is a startling economy to each thing Matisse depicts, a fixation on minimizing the number of times his implement need touch its medium to depaint a full expression of the human form. Between the larger canvas works and bronze statues at SAMA’s exhibition hang sketches Matisse did, often of subjects later depicted in nearby canvases, sketches in which Matisse worked to decipher the boundaries of his expression. Many charcoal drawings, necessarily black and gray on white, say “There! it can be done without color, all those patterns and shapes kept distinct, and so, I may fill it with whatever colors I wish.”

There is a learned fixation, as well, on luminosity, a play upon the realization a human eye has but three cones for discerning color but a hundred thousand neurons for contour, and therefore, whatever decorative value it provides, color is a thing our ancestors did without for quite some time (and no sooner did we sense color but our brains devised a filtration system for removing it from most light sources). So long as the contours of a treatment resemble a human face, Matisse demonstrated, it matters nothing if the beard is turquoise, the chin is tangerine or the hair is flaming purple; we see the world in black and white, and our eyes answer their most essential binary inquiry – human face Y/N? – many milliseconds faster than computers ever may.

Matisse, and here he followed Claude Monet, got at an idea best expressed like vision-as-narrative, a concession, or perhaps proclamation, we very much see what we are looking for and then remember nary a fraction of it – a form of honest rendering, to revise an American courthouse oath, which goes: The truth, never the whole truth, but nothing but the truth. When one remembers any Matisse painting an hour after seeing it, he remembers its colors, radiant and voluminous; first in the mind of both tyrant and tyro comes always the incredible breadth of Matisse’s inspired palette. And yet, and yet.

It is the solid blacks and whites, and grays between, that allow delineation enough in what signals our brains collect from our eyes to allow the colors to remain intact, and not make of them what muddiness should logically come of such swirling, competing hues. No one remembers Matisse’s black outlines, absorbed from Post-Impressionist predecessors and specifically Paul Gauguin’s studies of Cloisonnism, a way of making oil on canvas mimic stained-glass windows’ authority, that wrap most of Matisse’s objects, or the flat white paint that dots so many such objects, or all the matte-gray mirrors one sees, when he returns home and tries to remember his favorite piece, because Matisse mastered the narrative of human sight taught him by Renaissance masters like Rembrandt and Diego Velazquez, and then surpassed their understanding, inverting the harmony of their form, goaded doubtlessly by his cobber and competitor Pablo Picasso, and seeing what the human mind might sense through its retina, communicate to its brain, and retain in its memory.

But Matisse absorbed the masters’ craft before he subverted it, a thing lost on all but the very best athletes, managers, promoters, broadcasters and writers of our beloved sport, today: Every kid with reflexes thinks to carry his hands below his view, every new manager thinks he’s the first to read Dale Carnegie’s 77-year-old bestseller or any of its 77,777 knockoffs, every upstart promoter is certain he knows the city better than what dozen failures preceded him, every broadcaster discounts his viewers’ perceptiveness, and every young writer suspects no one before him dabbled promiscuously in first-person pronouns or exclamation marks.

In the Matisse works that now hang at SAMA, one sees most prominently an homage, irreverent, yes, but an homage nonetheless, to the 17th-century Dutch master Jan Vermeer. Matisse was on to the Dutchman’s every trick – academics today might argue whether Vermeer traced his subjects from the projected image of a camera obscura, but Matisse knew it straight away – and gently ribbed the master with fisheye distensions of planes introduced by a light source from the left, covered either by a curtain or open window. Matisse knew from a blessed combination of maturity (his 35th birthday preceded his originality) and deep observation what his influences were about and where to place the detour of his genius.

From empty local gyms to bankrupted managers, impotent promoters, plunging viewership and impecunious scribes, today the woes of our sport’s woeful state, contrarily, reduce often to a stubborn obliviousness of what preceded us.

*

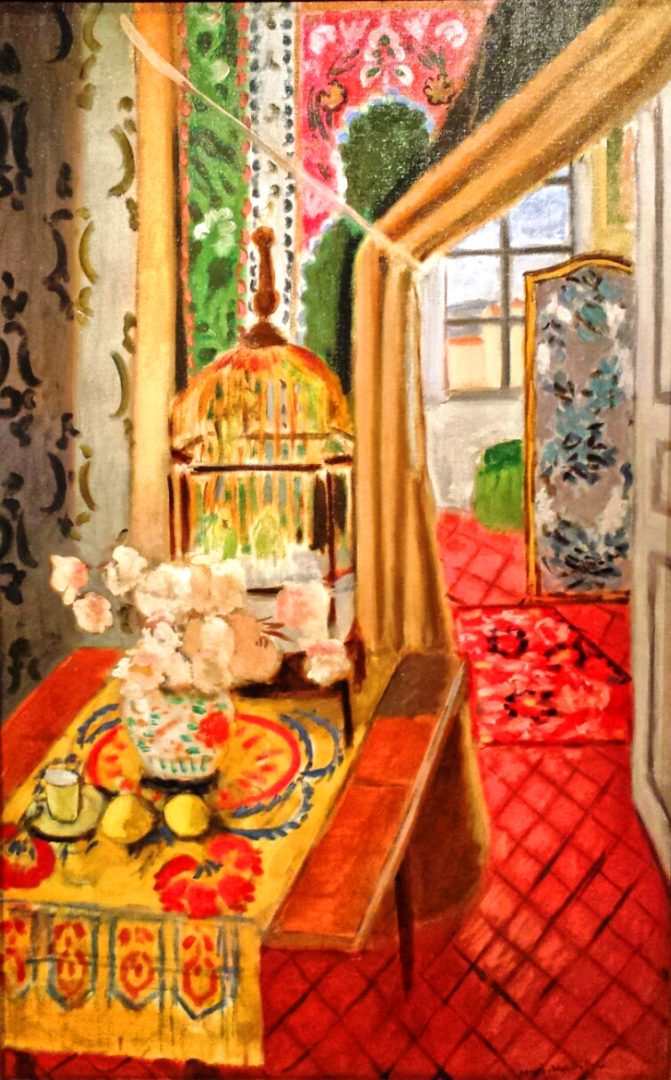

Author’s note: The photo above is of Matisse’s “Interior, Flowers and Parakeets” – a featured work in San Antonio Museum of Art’s current exhibition.

Bart Barry can be reached at bart.barrys.email (at) gmail.com