By Bart Barry–

SAN ANTONIO – Tuesday at Aztec Theater, the oldest theater in this old city, Saul “Canelo” Alvarez and James Kirkland announced their May 9 fight in Houston. Saturday at MGM Grand in Las Vegas, Keith Thurman decisioned Robert Guerrero. In between those two middling affairs, Showtime announced plans to honor its televised trilogy of Israel Vazquez and Rafael Marquez – a trilogy unlikely to be matched in quality or ferocity even by a 2025 highlight reel called “Premier Boxing Champions: The First 10 Years.”

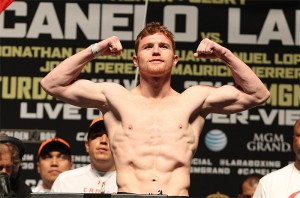

What Alvarez and Thurman have in common is above-average talent and a poor era; they are b-level fighters elevated to millions-dollar purses through some balance of mediocre opposition and needy fans. Alvarez is better tested and more beloved and unlikely to improve, while Thurman is more athletic, even while his power has moved with inverse proportionality to his opposition. What Vazquez and Marquez were, and made together, is another thing entirely.

There’s an inauthenticity to the televised experience, today, that wasn’t nearly so pronounced a part of our sport in previous decades. Boxing writers’ lamentations about television are well-noted and quite old, of course, and this isn’t intended to be so much another tired protest of the inevitable as a commentary on what’s worsened.

Boxing long preserved a griminess, a degree of filth, other sports lost generations before; boxing retained a sense of the unexpected in a way that made other sports appear overwrought and scripted. There was ever a touch of irony to this – with spectators accusing boxing results of being fixed, which they often were, even while phantom rules violations in the NBA and NFL influenced just as dramatically who became those sports’ champions. Television was a guest at boxing events, or at least telecasts felt like they were conducted by guests; proper boxing matches had a sense of inevitability to them, an implication this grievance would be settled, regardless of witness, at this time, on this evening, and television cameras just happened to be there.

Saturday’s NBC debut, instead, had other sports’ feel: We are here because television invited us, and do you know how great is the reach of public airwaves? and have you seen our incredible commentating team? and would you please have a listen to our soundtrack? If it did not feel quite scripted, it neither felt like a collection of brawls that were going to happen even if television cameras went dark. Aficionados are noticeably insecure about public acceptance of our sport, too, and that marked social-media depictions of a few good rounds in an otherwise poor night of NBC boxing with the usual trimming: Don’t you see, everybody, this is why you should love boxing as much as we do!

Tuesday’s press conference, or media event, as they’re now called since “press” – derived from printing press – no longer has any meaningful place at these clubland mashups where seats labeled Deadline Media get occupied early by women with enormous promotional posters and boys with eager black sharpies, and the deejay stands both closer to fighters and with a better chance of interrogating them than anyone carrying something antiquated as a notebook or pen, had promoters beseeching the partisan-Mexican South Texas crowd to show the world Texans were the very best fans by driving 200 miles to Houston in May to purchase the promoters’ product. Oscar De La Hoya was there, looking jittery as he’s appeared since warming up to fire Richard Schaefer (who must’ve watched Saturday’s NBC telecast and realized, much like HBO’s Kery Davis before him, he was disposable to Al Haymon as print media is), and of course Saul Alvarez and James Kirkland were there too.

Evermore, De La Hoya appears a refreshingly outdated model; he likes or appreciates the press and adheres to the olden-day rules of being unbothered by gliding through 20 minutes of frictionless inquiries so long as his inquisitors are equally unbothered by 20 minutes of countlessly refried cliches. There was a time De La Hoya was unique in the sport for his lack of sincerity. De La Hoya is no more sincere today than he was then, but our beloved sport now plumbs such depths of insincerity a De La Hoya sighting has all the charm of a throwback jersey; at least Oscar cares enough to smile and wave and remind us he was a great fighter who did fight other great fighters.

As an antidote to all that, last week Showtime announced it would commemorate the best trilogy to improve is airwaves, when it replayed Israel Vazquez versus Rafael Marquez. There appears nowhere on our horizon the likelihood of another such trilogy. The quality and violence of the combat shared between those two Mexican prizefighters, their willingness to avenge both defeats and victories, at a withering pace – they fought three times in 363 days (just after Vazquez stopped Jhonny Gonzalez in a particularly brutal affair) – is so far from what we have now it is barely believable Vazquez-Marquez 3 happened only seven years ago.

Then, as now, many in our ranks were discontent with boxing’s trajectory. Try not to imagine how bad things will need to go for us someday to look back longingly at Thurman-Guerrero.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry