Disorder to diminishing returns: Terence Crawford and boxing’s downward spiral

By Bart Barry-

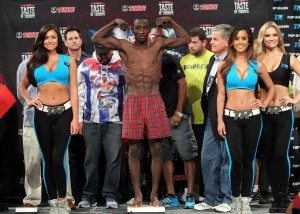

Saturday in Omaha’s CenturyLink Center, in what was probably another attendance record of some prepositional sort – in October, against a French speaker, after a Texas fight, under the rules of the WBO, within the American Midwest, without a doubt, beyond expectations – Nebraska junior welterweight Terence Crawford razed Haitian-Canadian Dierry Jean in 10 rounds. Before Jean was able to retrieve his check from the scorer’s table with a shrug, talk turned to Crawford’s next opponent: Manny Pacquiao, in his first last match, in April, on pay-per-view! And the shrugging commenced.

Anybody see Terence Crawford repeating as Fighter of the Year for 2015?

They can’t all be good twelvemonths, and to be fair, the exceptionality of Crawford’s 2014 was impossible in 2015, known forevermore in boxing annals as the year 0 AH (After Haymon), but Crawford, or at least his handlers at Top Rank, the incredible shrinking promoter, might have put in an effort slightly more inspired than what 2015 shined. There was the compulsory migration to a new weightclass, junior welterweight, that might’ve impressed if Crawford’dn’t already fought a better junior welterweight, Breidis Prescott, on no notice, in 2013 (2 BH). Then there was the inexplicable University of Texas venue in Arlington, on a campus even UT alumni needed to google, and a typically tough, hopeless opponent.

Saturday’s match, an achievement-award homecoming tilt, a way for Omahans to thank a fellow Nebraskan for excelling at some sport other than football, happened against a man not even fightweek festivities bothered embellishing. He was Dierry Jean, the Haitian-born Canadian smuggled out of Montreal to rehab Lamont Peterson in 1 BH, after Lamont got spincycled by Lucas Matthysse, just before Lucas got handled by Danny Garcia. Whatever the ratings boards say of Jean, and no, I don’t care enough to check, intuition says he’s roughly half the opponent someone of Crawford’s talent and pedigree should be confronting in his third match at 140 pounds, on HBO.

So bring on the Pacman!

That’s actually an uncharacteristically interesting fight if it happens in 1 AH, which it likely will not, because honestly, how often does anything genuinely interesting still happen in our oncebeloved sport? Faded as Pacquiao is, a return to 140 pounds – where he fought only once, stiffening Ricky Hatton in 6 BH – might quicken his movements some and make a fight entertaining enough to disarm the righteous rage aficionados feel about the performance, and postfight gracelessness, Manny and Coach Freddie staged against Floyd Mayweather in May. Disarm is perhaps a verb too far: Boxing is just beginning to experience the first sensations of the injury it suffered from The Fight to Save Boxing.

If the pay-per-view numbers are to be believed, and they never ever are, Mayweather took a 90-percent haircut, Pacquiao-to-Berto, and Gennady “Our Next Superstar” Golovkin didn’t do even half Mayweather’s new number, despite allegedly breaking Madison Square Garden attendance records not even the Empire State though to track till GGG’s invasion. The official model is probably broken, and adherence to it – basic cable to premium cable to PPV – almost assuredly will frustrate any who obstinately power towards it.

Bob Arum is not to blame. His legacy as a legendary promoter is assured by the company and fighters he built and the enduring changes he wrought (how do you think boxing got off free TV in the first place?), and he’s been semiretired, anyway, since Juan Manuel Marquez dangled Manny Pacquiao between life and death in 3 BH. What has happened to Top Rank since then is a descent that now accelerates.

There’s a chance all living systems follow the same spiraling pattern, and if they don’t, certainly boxing’s television model has: Disorder –> Negative Feedback (diminishing returns) –> Order –> Positive Feedback (increasing returns) –> Disorder.

The consolidation of broadcasting from many to few imposed an orderly system for exponentially increasing the revenues generated by select men like Mike Tyson and Oscar De La Hoya and Floyd Mayweather and Manny Pacquiao. This increased revenue summoned new agents, like Al Haymon, and disproportionately empowered a few men to move the sport according to their whims. And the more whimsically they behaved, the more revenue they generated till the order disintegrated in the spectacle of a network, HBO, despite having invested extraordinary resources in the promotion of two fighters, Mayweather and Pacquiao, being powerless to make them face one another.

The Fight to Save Boxing was not the beginning of disorder so much as its highest manifestation: A match no expert believed would please its consumers found the largest paying audience assembled in our sport’s history. What 30 years of splintering titles and feuding promoters and deteriorating talent pools could not do to obliterate boxing’s fanbase – decimate, yes, but not obliterate – May 2 did in less than an hour.

Aficionados’ hostility now makes them casual fans whose indifference ensures diminishing returns for every organism in the boxing ecosystem. Opponents of the truly talented are no longer talented enough to improve them, and the truly talented’s skills subsequently erode till they bore their audiences away or lose in matchmaking mishaps. Suddenly boxing is ubiquitous on free television, the last era’s Promised Land, and yet nobody cares at all. The negative feedback has begun in earnest, and while human technology ever has an acceleratory effect on its spirals, the last cycle took decades to complete and this one is barely begun.

Prizefighting, in the sense of men paying to watch other men bludgeon one another to unconsciousness, will endure, but prizefighting, in the sense of a match generating $500 million again, is finished for years, definitely, for decades, probably, and for a lifetime, possibly.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry