By Bart Barry-

Editor’s note: For part 1, please click here.

*

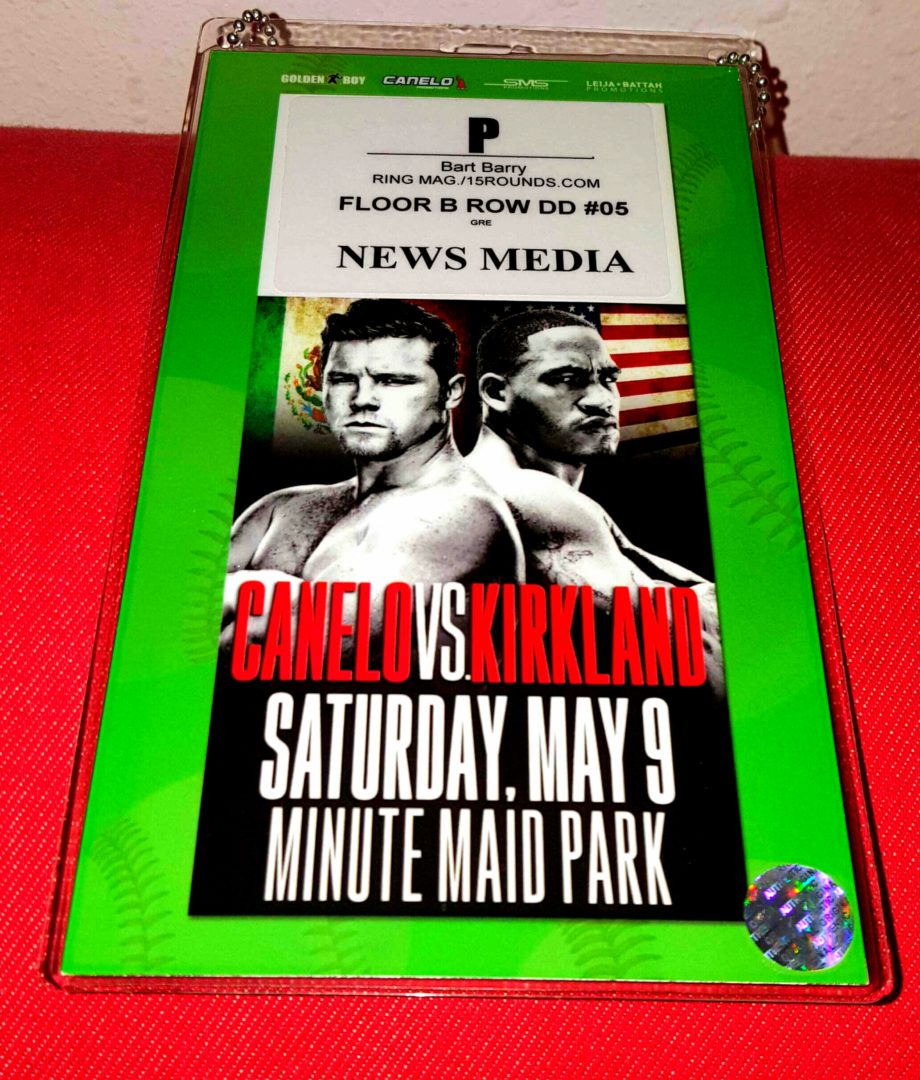

The May morning of 2015’s knockout of the year, the Saturday Mexican Saul “Canelo” Alvarez spearchiseled Texan James “Mandingo Warrior” Kirkland in Houston, no one was certain just yet how debasing for the sport of prizefighting 2015 would be, how mercenary, how joyless, but the previous weekend’s fare served notice to all aficionados, and the worst part, too: Mayweather-Pacquiao was what we asked for, demanded, allowed the sport to suspend itself in pursuit of, for five years that did nothing so much as hollow-out the fanbase by loitering in Las Vegas while more gymnasiums shuttered and fewer American boys explored boxing as more than a cynic’s plan-c moneymaking ruse, a trashtalking musicvideo to film after flunking football and basketball.

In March, Oscar De La Hoya promised Canelo Alvarez as a savior for the sport, and everyone applied the ironist’s filter, instantly and properly, hearing: Canelo Alvarez is the man the Golden Boy hopes will save his struggling brand. It was lost on no one how instrumental De La Hoya and “his” “promotional company” were to Money May’s ascent during the seven years De La Hoya vainly searched for someone, beginning with himself, to humble Floyd Mayweather; instrumental, in fact, is not strong enough – during the partnership years, Golden Boy Promotions was the fulcrum in Al Haymon’s lever, making De La Hoya and his former friend Richard Schaefer mechanically essential to a movement that, in 2015, changed its name from “HBO” or “Showtime” to Premier Boxing Champions, PBC, and began appearing on the same terrestrial television networks promoter Bob Arum convinced aficionados should be boxing’s rightful place (about a decade after Arum first moved boxing from terrestrial television, of course).

Very few pundits realized when Canelo fought Kirkland what an existential crisis the PBC presented, with its hostility to independent media and indifference to competitive matchmaking, and only marginally more recognize it today – choosing, symmetrically, to save such a collective revelation for the very moment their powerlessness to alter it achieves fullness and perfection (with writer David Avila a noble exception).

*

The May morning of 2015’s knockout of the year, the Saturday Mexican Saul “Canelo” Alvarez spearchiseled Texan James “Mandingo Warrior” Kirkland in Houston, brought merely one concern about a tardy arrival at the ballpark: There mightn’t be time for socializing and reminiscing with writers Kelsey McCarson, a fellow Texan, and David Greisman – not a fellow Texan but doing his level best that week to be one.

My fears were misplaced. The endless and uninspired undercard offered plenty of time for chatting and sharing a photo on the grass roamed by Astros outfielders. Seated directly in front of me, too, was Welshman Anson Wainwright, once a contributor to this very site and today a regular contributor to The Ring’s always engrossing “Best I Faced” series.

The ranks have thinned since my first visit to pressrow in 2004, and in the next five years the PBC’s subversion of media access will end either the PBC or pressrow, but wherever more than a halfdozen writers are gathered at a Texas fightcard, good health and good humor shall remain the rule.

*

The May morning of 2015’s knockout of the year, the Saturday Mexican Saul “Canelo” Alvarez spearchiseled Texan James “Mandingo Warrior” Kirkland in Houston, anyone who told you he was sure what to expect from Kirkland was embellishing the case a bit. Kirkland had done his preparations with San Antonio’s Rick Morones, instead of Austin’s Ann Wolfe, and while it likely made no difference to the outcome – Canelo is simply a higher level fighter than Kirkland, whatever Kirkland’s conditioning – it was not the plan in March when the Canelo-Kirkland presstour made its way to Alamo City’s historic Aztec Theatre and a pleasant and plump Kirkland confidently and ominously reported his manager was in negotiations with Ms. Wolfe.

Kirkland is a known entity in San Antonio, not quite a legend but one remembered in local gyms for having manstrength even as a boy. Kirkland was the right person to make Canelo look spectacular, a lie-detector type, rough and unrelenting, one to establish quickly the difference in caliber between a champion like Canelo and a local attraction.

Canelo had not before had a man of Kirkland’s class run across the ring at him on first bell and begin hurling punches without regard for anyone’s safety, but he managed the incident as if he had, and many times. That poise is a large reason Gennady Golovkin apologists, those who’ve amplified the Golovkin-camp line for three years, the risible assertion GGG, despite never fighting anywhere but middleweight, is ready to fight any man between 154 pounds and 168, strongly prefer 2016’s superfight happen at 160.

If that fight happens, this much will be made immediately clear: While Canelo Alvarez has fought at least one man considerably better than Golovkin, and maybe several, GGG’s reign of terror at middleweight has yet to include anyone close to Canelo’s talent.

*

The May morning of 2015’s knockout of the year, the Saturday Mexican Saul “Canelo” Alvarez spearchiseled Texan James “Mandingo Warrior” Kirkland in Houston, the 200-mile eastwards drive got justified by both men’s reputations and the increasingly unfortunate realization Canelo Alvarez will be the Mexican prizefighter most remembered in our current era – despite his technical inferiority to each member of our last era’s Mexican triumvirate: Juan Manuel Marquez, Marco Antonio Barrera and Erik Morales.

Because of Mexican television rights and other complexities, including their standard-issue dark heads of hair, the best fighters of the last era accomplished fractionally much celebrity in their homeland as Canelo did before his 25th birthday. Canelo cannot be blamed for that. He’s squandered no opportunities, whatever his limitations of speed and power, and he remains a prompt and courteous interview even when he does not need to be. He has far surpassed his only realistic competition for Mexico’s heart, “Son of the Legend” Julio Cesar Chavez Jr., and he’s done it with discipline and class.

Any aficionado seated ringside for Canelo-Kirkland and knowledgeable of Mexican prizefighting history – practically a redundancy, that – left the experience balancing a sentiment like this: An era of Mexican prizefighting could do better than having Canelo Alvarez as its standard bearer, yes, but it could also do much worse.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry