By Bart Barry-

PPV Weigh-in 11-20-2015

WBC Middleweight Title

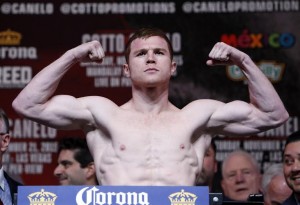

Miguel Cotto 153.5 vs. Canelo Alvarez 155

photo Credit: WILL HART

Let us have no more talk of Khan’s exceptional bravery in waging a fight everyone knew he would not win, already, because if we do that we must also credit Canelo’s equal bravery, and how badly does anyone wish to do that? The 19th century military theorist Carl von Clausewitz teaches us courage requires a sort of symmetry that relies necessarily on a doubtful outcome. Rarely is there cowardice in boxing; an absence of bravery in the ring manifests itself as resignation caused by a doubtless outcome, not openwinged flight.

To be courageous in victory a winner must entertain doubt of a contest’s outcome; to be courageous in defeat a loser must also retain doubt about that outcome – when a 300-pound bouncer snatches the consciousness from a drunk 150-pound fratbro no one credits the bouncer’s courage and, quite properly, no thinking person credits the fratbro’s bravery either. Von Clausewitz’s insistence on a doubtful outcome makes courage an intensely personal quality, a thing only its bearer can certainly audit. As it should be.

There are no fans of reductionism here, so let us traffic in probabilities and possibilities. Is it possible Amir Khan, a fighter 29 of 30 experts expected to lose, did not expect at any time during the proposal and promotion and performance of his fight with Alvarez that he might possibly win and went through with the discombobulating ruse only to amass a fortune? Yes, definitely possible; no, definitely not probable. Is it possible when Alvarez felt that first underpronated right cross from Khan in round 1 Canelo thought, “This is madness, I’m in with a beast, my victory is nigh impossible, and my survival unsure!”? Again possible, not probable.

Somewhere between these poles is where most of life and all but an instant of Saturday’s match happens/ed. Whatever postsalesmanship went off during the telecast with the team’s squinting to assure buyers they’d gotten at least nine minutes of competitiveness more than feared and Harold Lederman ably ratifying their pitch, writing as one person who picked Canelo to win by knockout I can offer without equivocation there were not three seconds of the 900 that comprised the opening five rounds during which even a pinhole of doubt flashed my mind. Khan was going to sleep unless Andre Ward’s trainer mounted the apron midround.

Frankly one didn’t even need to watch Khan’s customarily jittery approach to know it; Canelo’s mien told the entire tale. Certain as I am I did not doubt Canelo would take Khan’s consciousness is how uncertain I am I watched Khan as more than a prop in the opening five rounds – like a fidgety double-end bag. It was not until the fifth round brought palpable contempt in Canelo’s bearing, though, the outcome became doubtless. Canelo got Khan with the same move with which Canelo cut James Kirkland’s lights a year ago in Houston. He even got Khan’s hopeless, unwinding left to play corkscrew and win Canelo his second consecutive knockout of the year, and congrats on that.

Canelo dishragged Khan and it was magical.

The entertainment runnerup Saturday was the contortionist’s trick of HBO broadcasters mentioning repeatedly Mexico City’s WBC and its suddenly binding resolution to make the HBO middleweight champion of the world the WBC middleweight champion, without mentioning the WBC by name. It felt born of what fantastic consequence the nearly inconsequential media assigns itself; with a new man at the helm of the WBC here’s a chance for him to get his agency’s acronym back in our throats (even if half our infomercial series and all of our introductions and postfight festivities are a voluminous WBC endorsement in highdef) but if the new guy chooses not to strip with urgency his country’s most popular fighter, why, he can say adios to a future “Real Sports” feature and an edgy “On Mauricio Sulaiman” film and even a perky journalist saying amazing things about him on “The Fight Game.”

Canelo is selfaware and arrogant enough to know HBO and the WBC need him much more than he needs them, and good luck dictating terms to him about ratifying Gennady Golovkin as the greatest middleweight champion in recent memory (an authoritative prepositional phrase we use when we’re too young to know very much or too lazy to do research more than google). Golovkin will fight Canelo on Canelo’s calendar and by Canelo’s rules or Golovkin will cost HBO increasingly more money in promotional subsidies subsidized by revenues from Canelo’s pay-per-view matches. That seemed to be the message in Canelo’s postfight use of the Spanish term “mamadas” (better even than the colorful translation it got): Your network can take the funds I raise and use them to erect and decorate another fighter at my expense but before you say any of this to my face, Max, remember who works for whom, who pays your salary and Gennady’s promotional fees.

If David Lemieux starts dieting right now there’s a good chance he can make 155 for Sept. 16.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry