By Bart Barry-

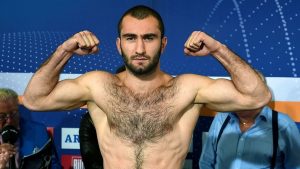

Saturday in Moscow Russian cruiserweight champion Denis Lebedev lost his title by split decision to Russian Murat Gassiev by scores that were at best wide and at worst wrong: 114-113, 112-116, 111-116. Gassiev dropped Lebedev in round 5 and fought ably in most every other but did not appear to punch enough to depart Khodynka Ice Palace with Gassiev’s jewelry.

It was an honest prizefight between two men who knew how to do it and went about the labor of bludgeoning one another quite a bit differently: the southpaw champion, shorter and thicker, moved at times nervously but generally effectively and squaredup to turn his left cross to a hook round Gassiev’s guard, and the orthodox challenger, tall and coiled, landed far fewer clean punches but absorbed his opponent’s blows more indifferently and benefitted from a bodyshot knockdown in the middle rounds that gave two ringside judges liberty to weigh his work generously. It was an honest viewing experience for American audiences, too, because it came effectively bereft of biography – though the cornermen, the once-quotable Coach Freddie and enduringly obnoxious Abel Sanchez, surely biased some American eyes somewhat.

But that doesn’t explain the judging and for once it’s good not to bother autopsying scorecards for improper interest. On the Russian broadcast it did not appear Gassiev did sufficient to unstrap the champion but the acoustics of a YouTube feature from the other side of the world might be suspect so one never errs giving ringside sounds and those who experience them benefits of scorekeeping doubts – for the sake of one’s own peace of mind or at least solace. Lebedev was indeed busier throughout and controlled no fewer than eight of the match’s opening nine minutes then got caught a while after that with a left hook to the liver, a quite odd thing for a southpaw to collect, and dropped without a standard halfsecond’s delay as if he knew how badly things’d go when the liver’s report reached his brain and wanted to get in position for it, and the tenor of the judging if not the action being judged shifted dramatically, or else Gassiev’s punches simply sounded that much more ferocious at ringside than they looked on video. The widest scorecard came from an American judge in Moscow watching two Russians trade hands, and one hopes therefore he didn’t bring a rooting interest to a card that otherwise felt lopsided, though the IBF sure flew him a long way to that ringside seat.

If Gassiev won fairly he did so by punching much harder than the champion because it sure as hell wasn’t Gassiev’s defense, pedestrian, or head movement, scarecrowlike, that brought his W and new title. The idea of that title is worth a revisit because it addresses the way fights are scored and the way aficionados think fights ought be scored, and they’re not the same.

Barring a decisive act the man being watched more by a judge during a round will win that round from that judge. None of us, that is, watches impartially enough to keep his eyes fixed on the floating cube of space between two combatants, following each fist across the cube’s threshold and judging its effect from there; each of us begins each round watching one of the two fighters and why we watch that fighter is a plethora of subjective things like identity and empathy and psychological goingson we couldn’t catalog exhaustively if we had unlimited time and inclination. Yet we dive headlong at the most obvious considerations when judging judges, which is fine actually because in large part it’s what judges sign up for.

Somewhere round here is the genesis of the idea a challenger must beat a champion more decisively than a champion must beat a challenger – not because any judge’s scorecard (that isn’t prefilled anyway) is prefilled with a handicap for the challenger but because, by virtue of the precious metal he wears round his waist when he steps through the ropes, a champion brings a presence scorekeepers’ eyes find irresistibly shiny – the champion is the default object on which a judge’s eyes fix. Nobody said it had to be like that in the beginning; it turned out like that often enough to become probable and then men who trained challengers decided it was an apt tool to tell their charges in camp the champ would be entitled to every close point, and soon enough those challengers became champs themselves and decided such entitlement, while unofficial, was a binding rule. One of them probably said that much in an interview once long ago, and drunken fanatics have been loudly quoting him ever since.

If members of the Sergey Kovalev camp didn’t cite this rule directly or publicly after their charge’s narrow loss to Andre Ward a few Saturdays back they surely alluded to it privately and attributed to bias an outcome decided by American judges’ susceptibility to a jingoism that overwhelmed the subconscious bias Kovalev’s waistwear should’ve brought. Perhaps. But Saturday a Russian champion did about as much to defend his title in Russia as Kovalev did in America and got the same sort of result though he lost by a greater margin in his home country than Kovalev did in Ward’s home country.

And that returns us ever and again to there being but one way to win a prizefight objectively and that is by knockout. The rest is noisy twaddle.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry