Decades Under the Influence: Joe Smith Jr. Retires Bernard Hopkins

By Jimmy Tobin-

Saturday night, at The Forum in Inglewood, California, Bernard Hopkins tempted boxing’s unwritten rules for the last time. Inviolable as they are, those rules made an example of him. Hopkins’ farewell fight ended with the 51-year-old where he planned to be: beyond the ropes, surrounded by his supporters, the object of every fixed gaze in the arena. Except he reached that position courtesy of union construction worker, Joe Smith Jr., who hammered Hopkins through the ropes and onto the floor below, handing “The Executioner” his first stoppage loss in his very last fight.

Retrospectives aplenty are promised in the coming weeks, and Hopkins’ career is rich enough that sifting through his past for celebratory moments presents a unique challenge. Every fighter has such moments—Smith himself, despite being a relative unknown last year, now has two—but unlike so many of his contemporaries, with Hopkins it is selecting from abundance, not scarcity, that provides the challenge.

Reference to his protracted dismantling of Felix Trinidad—a flawless performance with few rivals since—will figure prominently, as will his humbling of self-proclaimed “Legend Killer” Antonio Tarver, so completely embarrassed by Hopkins that night he was reduced to asking trainer Buddy McGirt for ways to simply survive. Perhaps Hopkins’ one-armed destruction of Antwun Echols will also be romanticized and retold. More recently there is this: in 2014, Hopkins, at age 49, lost a unanimous decision to Sergey Kovalev in the fight that ratified the Russian. It speaks poorly of the division that a win over a man near fifty could serve such a purpose, though it is testament to Hopkins’ mystique that in his career’s third decade he remained a standard for more than longevity.

Even the version of him that fought Kovalev did not step through the ropes in Inglewood, however. And if Hopkins should choose to fight on he will do so knowing that the ring no longer welcomes him. Smith put Hopkins on borrowed time with a short right hand early, and what followed was all-too-inevitable. Hopkins lost the fight, his aura of indestructibility, and some of his dignity to a fighter who would not have ferreted a round from him in his prime.

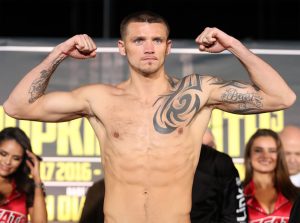

The headbutt that opened a cut over Smith’s left eye seemed barely to register with the Long Island fighter, nor did the lead right hands that Hopkins bounced off his head once or twice a round. Kovalev suffered perplexing moments against Hopkins, Jean Pascal seemed to mentally unravel when Hopkins employed his intimidation tactics. Smith, however, perhaps because he knew there was but one path to victory for him, knew that, having interpreted the effect of his blows, that path was the only one he would need, betrayed not a tremor in his resolve. He simply followed the aged fighter around the ring, kept Hopkins at the end of his punches, and swung with the express purpose of bagging a trophy kill.

That says something about Smith, about how he will comport himself—if not fare—against the better opponents he has now earned the right to face. But it also speaks to how little Hopkins, his body softer, beard grayer, had left. Smith crossed his feet in pursuit, yet Hopkins had not the legs to escape him; Smith telegraphed his punches, yet all Hopkins could do was steel himself against their effect. Take nothing away from Smith, who did what a professional fighter should to an opponent who had little business sharing the ring with him. If Hopkins does not belong in the ring with Smith, however, he certainly does not belong in a ring in a prime television slot on a premium network. That has been the truth for years, given Hopkins’ spoiling tactics, his preservatory style, and there is no longer sufficient argument to suggest otherwise.

The image of Hopkins careening through the ropes, sent there by the fists of a man with “The Future” emblazoned on the front of his trunks is lasting. So too was Hopkins’ response. A survivor par excellence, Hopkins’ interpretation of his final departure from the ring is both untenable and predictable. Asked about the action that precipitated his trip through the ropes, Hopkins suggested Smith shoved him out of the ring, so frustrated was he by Hopkins’ right hand, elusiveness, and body work. No manipulation of the facts can support such an interpretation: Smith knocked Hopkins senseless with a right and did not stop punching until Hopkins had fallen out of reach. When Hopkins came to he was in no shape to continue, and he knew it; knew too that the insult visited upon him exceeded his injuries. So he fabricated a story absurd even by the standards of a man concussed. To witness how deeply wounded Hopkins was by the outcome of the fight is to understand that he will cling forever to this revisionist history—and do so knowing full well the truth.

The truth is Bernard Hopkins took a professional prizefight in his fifties, miscalculated, and was treated as any fighter in his fifties should be, less boxing become so talentless that even a man half a century old can mock its ranks with his presence. It was a humiliating defeat, one that will haunt Hopkins not only for its result but for what that result confirms: the even he must bend to the rules.