By Bart Barry-

Recently my Saturday hike saw a canine companion turn instantly from goldenfleeced cutie to predatory lightning bolt. Still more recently Netflix recommended a very good documentary – “Ice Guardians” – about professional hockey’s enforcers, the players whose tenures in the NHL begin and end with their readiness, willingness and ability to fight. As this remains a column nominally about fighting consider what follows a form of crosstraining, a means of sharpening one’s afición by mulling some ungloved acts of violence.

Kiwi is a three-year-old cocker-spaniel mix who weighs little over 20 pounds and swings widely and acutely between affection and surliness. He is a carnivore, of course, with a taste for Texas barbecue that approaches lunacy: He prefers his ribs dirty, covered in meat, and doesn’t clean them so much as masticate the entire organ – muscle, tendon, cartilage, bone, marrow. When he’s had roast beef he tends to take a small and fluffy blue whale toy and put in much work, throttling it with a series of rapid neck twists, smashing it to the carpet then throttling it some more. It’s not cute or menacing, quite.

The role of enforcer in the NHL is, according to enforcers, entirely distinct from the role of goon – a disparagement used in the game at most all levels for a player whose lack of skill forces him to choose brutality over aesthetic options like passing or shooting or defending cleanly. An enforcer creates a preventative tension on the opposing team’s bench, acting like an insurance policy for his team’s talentful players who subsequently maneuver with the freedom of knowing nothing untoward or particularly physical will befall them. To hear enforcers explain it, their menacing presences govern other teams’ wouldbe scofflaws more certainly than lesser deterrents like suspensions or fines or even lifetime bans do – those deterrents are abstractions, where the threat of a large man’s bare fist racing from your nose to hypothalamus is a deterrent that is objective.

Guadalupe River State Park sits 30 miles due north of San Antonio and has a main entrance used by hikers and campers and bikers and tubers, and a back entrance with a gate that allows hikers alone. The backentrance trail winds through woods and meadows before descending to a river overlook, and it’s nearly always empty enough for Kiwi to gambol without a leash.

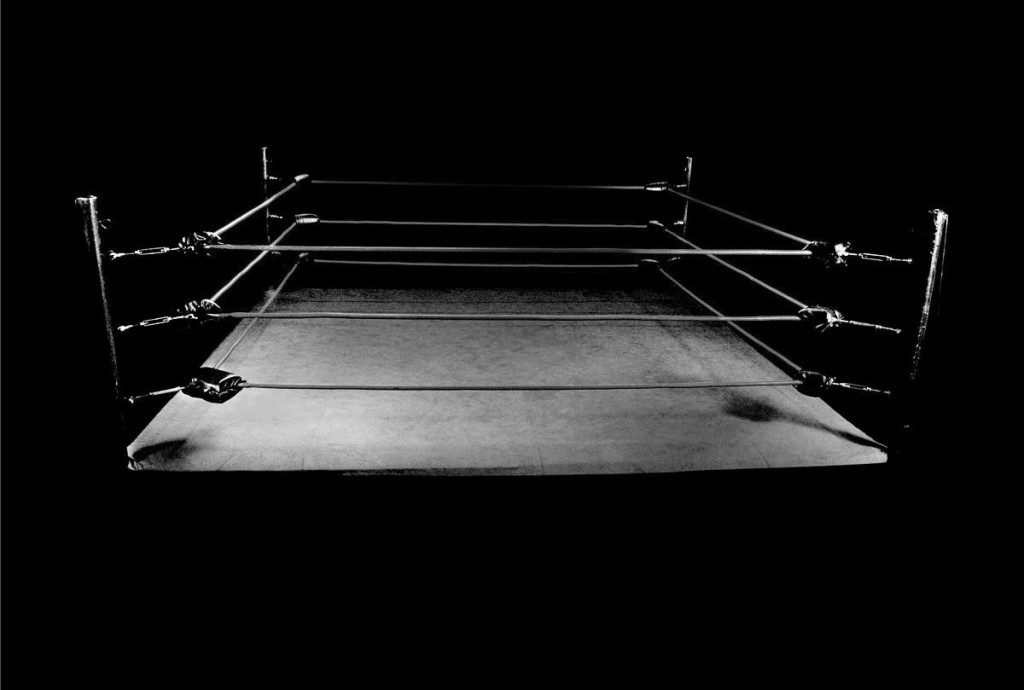

There is no type of combat like hockey fighting. Begin with the idea of trying to gain purchase on a frictionless surface. If you punch your target without having a hold of him, physics’ equal and opposite force sends you impotently backwards at the decisive moment. What you have to do, then, is grab hold of his jersey with your lead fist and pull his chin into your jab while cocking your back fist for a blow most concussive you verily do not wish land on his helmet or faceshield. Of course, he’s trying to do the very same, and the trick is tricky enough to turn th’t the NHL sees very few knockouts, even while most every fight ends with a knockdown of some grappling sort. In the good old days, as it were, before fightstraps and other such accoutrements, the goal was to get your opponent’s jersey over his head, extending his arms involuntarily, the better to lash him savagely with right uppercuts. Prizefighting is sportsmanlike and orderly by comparison.

The small armadillo may have been lame or lost or merely careless when it caught Kiwi’s attention. Kiwi, who’d dashed and trotted through a couple miles of rugged Hill Country terrain by then, breathed heavily with his tongue out, the better to scoop air in his throat. Less than a second after the armadillo made some fateful sound I did not hear, Kiwi’s mouth was shut, his ears up, and he bounded off the trail. In a single, silent motion, he rammed the armadillo with the bridge of his snout and knob of his thickboned forehead, putting it on its side, diggerclaws frantically scrambling. Once Kiwi’s lower jaw got in the armadillo’s fleshy underside, the throttling commenced. The sight became natural and horrifying, naturally horrifying, horrifyingly natural.

The biggest surprise “Ice Guardians” holds for anyone who’s played the game at any level above peewee is the surprise its laity commentators describe at their discovery NHL enforcers are actually decent men who are preternaturally loyal to their teammates. Raised in a bubble of superhero flicks and prowrestling villains, one assumes, these professors and doctors imagined psychopathy alone might lead a man to make his living punching other men. It’s an irony initially lost on them a dispassionate psychopath might make the very worst sort of enforcer, detached as he’d be from his teammates’ suffering, hypothetical or actual; whatever their size or temperament, NHL enforcers are generally men empathetic to a fault.

Kiwi’s teeth acted like saws while his neck torqued infinities, one two, then smashed the flailing armadillo on the earth – the way he’d practiced his toy whale for three uneventfully domestic years. Then another ramming to put the armadillo bellyup and another throttle throttle smash. Three altogether till the armadillo’s vital red organs bubbled orange out its chest while its legs went from twitching to ticking, animation dwindled. The job finished in 15 seconds, Kiwi wandered off and left me to end the little creature’s suffering. When Kiwi returned to the armadillo’s warm carcass, having hungrily licked the blood from his teeth and gums, he gazed curiously from the armadillo to me like “What have you done, pal?”

There’s lots of beerdrinking in the NHL, even more in NHL lore, and one imagines nobody better to have a beer with than an NHL enforcer. A paragon of masculinity in a profession that cottons to nothing effeminate, the enforcer speaks softly if directly, laughs loudly and ensures everyone gets home safe. By the time he ascends to the NHL, the enforcer is capable of precise, professional violence – which lets some forget how he was selected years before to become an enforcer. In a sport of Irish tempers and irrational pride, the candidate enforcer showed a lower threshold to offense than his peers and a unique propensity for violence. And a strict adherence to the game’s code: A professional hockey player settles differences with the knuckles of his bare fist, not the lumber in his gloves or the razors on his feet.

By the time we got back to the car, a couple miles and 45 minutes later, Kiwi was bouncing and yipping like usual, tail wagging, licking my chin and panting, returned to his euphoric, playful self.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry