By Bart Barry-

This is not a trigger warning but a preamble. What follows is a consideration of fantastic writing about men, the sort of writing we aspire to do while treating our beloved sport, that happens to be written by a gay man about gay men. This column will attend neither to prurience nor politics. Rather it’s a coincidental product of a Monday falling within LGBT Pride Month after a weekend I spent reading fiction more than watching boxing.

This space once was about writing much as it was about boxing. Though it had floated away from most concerns about description by the time it began in 2005, its author nevertheless fancied himself quite good at description when called upon, since like most writers, his ability to describe objects better than others do was what first got him recognized by a teacher (in this case, Ms. White, fourth grade).

The move away from descriptive writing was not conscious, quite, but happened via a definitely conscious choice to avoid “writing” in the meretricious sense of the term, to avoid those squeamish points in all forms of literature when an author suspends subject to go on a look-at-me-I’m-writing! riff. If memory, unreliable as ever, manages to serve, the move away from descriptive writing happened in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, 2002, when a visit to a writers club found a bunch of selfcelebrating folks rarely bothering themselves with the unglamorous toil of writing while unrarely sharing brief moments of inspiration that sparked “writing”.

If this reads like an oddly hesitant preamble perhaps it is born of nervousness about treating what follows justly. Well, anyway, off we go:

“. . . as I waited, and looked around at the dozens of bodies, squatting, lying, straining, muscles sliding to the surface in thick-veined upper arms, shoulders bending and pumping, the sturdiness of legs under pressure, the dark stains on singlets that adhered to the sweating channel of the back, the barely perceptible swing of cocks and balls in shorts and track-suits, with, permeating it all, the clank and thud of weights and the rank underarm essence of effort.”

I read that about a month ago and decided I’d not read before the male body or a collection of male bodies so aptly described. That passage happens about 50 pages in to Alan Hollinghurst’s masterfully executed novel “The Swimming-Pool Library”, a firstperson account of a young gay man in London in the early 1980s, remarkable for its profiles and voice and its numerous descriptions like what’s above. What makes these descriptions remarkable is their departure from the way men’s bodies generally get described by straight authors, both male and female.

Straight men describe other men’s bodies like sanitized, actiontaking machines – on the rare occasion a muscle ripples it does so to cause an act: the shoulder vibrated as his left glove struck the opponent’s ribs. Straight women do something similar, though describe qualities of masculinity that are physical mostly by coincidence:

“Mr. Darcy soon drew the attention of the room by his fine, tall person, handsome features, noble mien, and the report which was in general circulation within five minutes after his entrance, of his having ten thousand a year.”

Contrast that with what Hollinghurst does. He sees and smells and hears men in a way crossed between a predator and a food critic.

Would it help our descriptions of prizefighters in the act of prizefighting if we saw them through a lens of sexual attraction? Quite possibly. It would sate, too, any writer’s search for originality. But there is, of course, the rub: Such things are not easily faked since most pathways to forgery betray their takers – you can imagine your favorite fighter is a woman and describe him thusly but imagining him treating you like a woman is another leap entirely, and unless you have both you’re not fooling any careful readers or even careless readers’ intuitions.

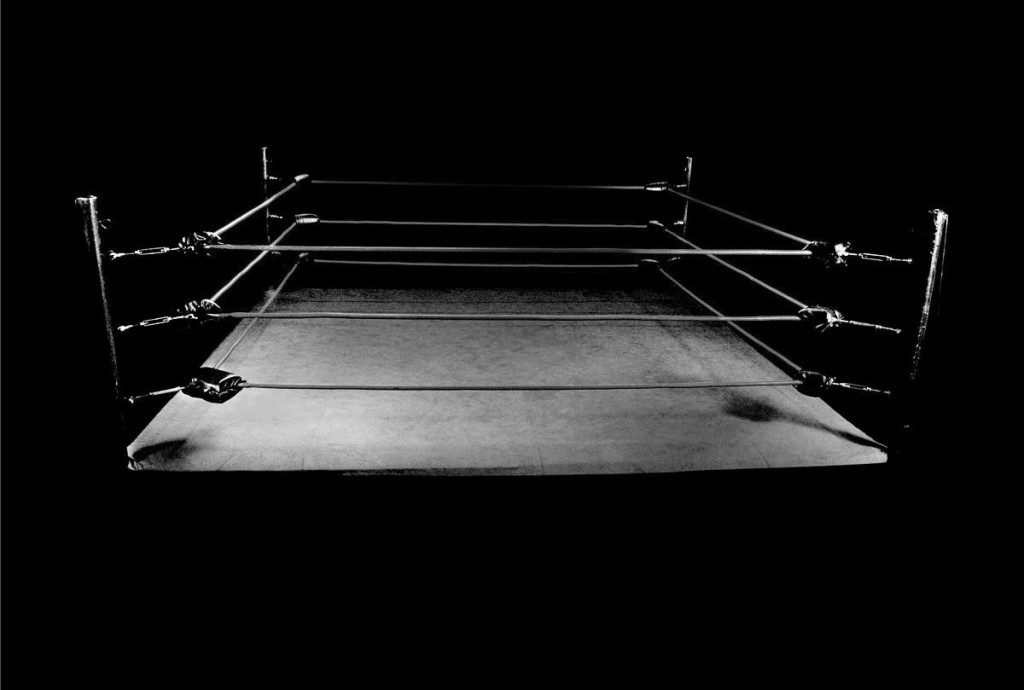

Good news. There is some boxing in “The Swimming-Pool Library” to leaven this Pride-month celebration of fine description. Hollinghurst’s narrator attends a night of youth boxing and offers it his often irreverent voice:

“One trio of teenage stylists bawled their encouragement while grinning and chewing, selfconscious, acting manly, caring and not caring.”

and

“After brief deliberations between the ref and the officious, serious judges (this was their life, after all) the unanimous decision was announced.”

and

“The mood here also was one of pure sportsmanship, of candid bustle, like a chorus dressing room.”

There is one more element to this novel, a historical one, that recommends it. Lost in the recent events of European marriage-equality referendums and an American Supreme Court decision is the matter of 16th-century British sodomy laws (inherited round the world) and their successors and their arbitrary and generally cruel enforcement in our lifetimes. In a few episodes Hollinghurst shows how very easily it was to be entrapped and sentenced to jail time for a man who pursued, if he did not consummate, a sexual relationship with another man. Undoubtedly this charged the exciting act of seduction with danger’s energy right up till the moment it didn’t, when, with a thud, a man’s hormonally induced sense of invincibility disbelievingly crashed into disbelief.

And of course no irony is lost on Hollinghurst: How very much serendipitous companionship awaited a gay man sent to prison for gay acts. Or is this merely an empathy offramp taken by a straightmale reader – some way to dull what a profound sense of injustice sometimes happens in us?

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry