Column without end, part 18

By Bart Barry-

Editor’s note: For part 17, please click here

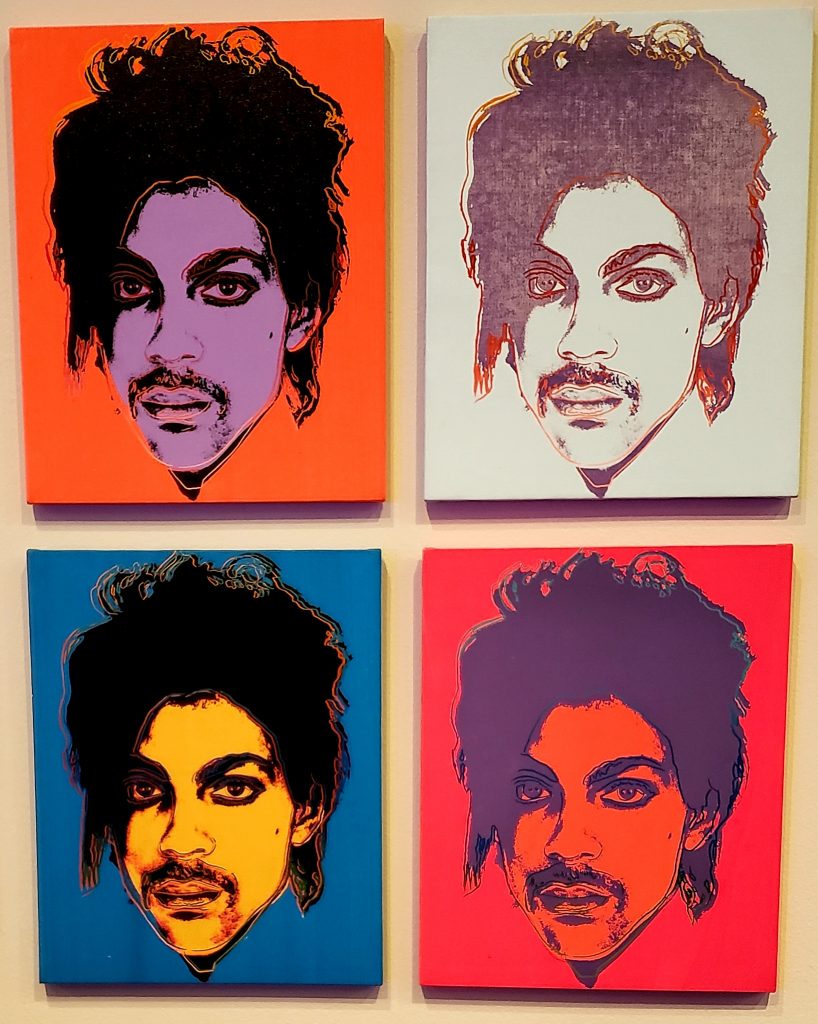

SAN ANTONIO – This city’s McNay Art Museum, which

has figured heavily (for an art museum) in this ostensibly-about-boxing column,

since 2010, recently opened an exhibition, Andy Warhol: Portraits, that appears

to have no tie-in whatever to our beloved sport. I revisited the exhibition a few hours before

writing this, unable to imagine a suitable subject, and sat so long at a lobby

table afterwards a friendly security guard came over to tell me I looked tired. Let that temper what you expect of this.

Nearly a decade ago The McNay had a different

Warhol exhibition that opened round about the time “Son of the Legend” Julio

Cesar Chavez Jr. put the wood to “Irish” John Duddy in Alamodome, in what would

be Duddy’s final prizefight. The editor

of a boxing magazine asked me to pitch him a unique idea for a story –

“anything out of the ordinary” – and I complied with an idea about this Warhol

exhibition, a visual dissection of Warhol’s fascination with celebrity and its

effect, being open in the same city at the same time as boxing’s greatest beneficiary

of celebrity. The pitch went nowhere, a

destination shared by the story I wrote instead for the magazine, and I made a

column of the idea.

(Actually, a quick search through the archives

reveals barely half of what’s above is accurate; “Andy Warhol: Fame and

Misfortune” opened in February 2012, not June 2010, and since by then Chavez

Jr. had beaten Duddy and Sebastian Zbik and Peter Manfredo, perhaps a story

attributing the whole of Chavez’s fortune to name recognition wasn’t the crackerjack

idea memory recalls.)

Out of the parenthetical but influenced by it: Memory

is many parts imagination, something confirmed by most adult accounts of childhood

that begin “I see myself . . .” as if that’s what children do when, say, riding

a bike – look at themselves, instead of their front tire or whatever terrain it

touches.

If Warhol never directly addressed memory’s inaccuracy,

and perhaps he did somewhere, prolific as he was, he understood part of the

appeal of his portraits to their subjects lay in a capacity for overwriting

memories. Warhol was a favorite

portraitist of aging celebrities because his minimalist approach to depicting

facial skin removed wrinkles and most blemishes (except for his Dolly Parton

portraits, which are better than the Marilyn Monroe portraits precisely because

Parton’s face had more imperfections).

Warhol very much made art for life to imitate and prophesied our

contemporary socialmedia obsession in any of his dozens of commentaries about

Americans and fame.

Floyd Mayweather would look good in a Warhol

portrait, methinks. I happened on a Fox

Sports promotional movie about Manny Pacquiao last week by accident and tried

to see Mayweather through his fans and commentators’ eyes, being removed as we

are now from the relevance of Mayweather’s schtick. What I looked for was elegance; what little I

recall of his victory over Pacquiao was Pacquaio’s unwillingness to throw

punches and subsequent inability to strike Mayweather, our defensive wizard. But what I saw instead of elegance was skittishness. Not during or after Mayweather got hit but

when the prospect of his getting hit happened: Confident-to-flinching-to-confident-to-flinchyflinching. It was not elegant.

Of course this was a movie to sell us Pacquiao’s

upcoming tilt with Keith Thurman, and it behooves nobody at Fox to concede

Pacquiao is diminished from the man who got whitewashed by Mayweather, a man

who was fractionally potent as the one who dashed through Barrera and Morales

and Marquez. Still. In hyperdefinition, Mayweather’s

squinchyfaced pullback looks nigh bitchy.

Warhol would remove that. If Warhol was not quite enamored of money as

Mayweather claims to be, he was doubly enamored of money’s effect, and Mayweather’s

selfstyled fixation on money might’ve enchanted Warhol with a question like: If

a man who is by no means the world’s best at making money allowed the last 1/3

of his career to be consumed by making money, a man who was the world’s best at

his actual craft, does that make money omnipotent or the man cynical?

This is why I looked tired in the lobby. A different range of thoughts happened on the

short, slow drive from The McNay to The Pearl, where this column got wrote: Is

the racing line elegant? is the racing line what Henri Matisse was after? is

Matisse better than Warhol, for eliminating pathways to imitation, or is Warhol

better, for spawning generations of imitators? how much should even a column

such as this be dedicated to a concept, the racing line, you understand at best

partially?

The racing line is a way automobiles may go

fastest round curves. It’s not the

shortest distance, as that would be the inside line, and it’s not a good way to

go at a constant speed. Rather, it’s

effectively the straightest way to go round a halfcircle – start wide, cut the

apex, end wide – and by being the straightest line it is the route that allows

the earliest moment of maximum acceleration.

If you regularly take the racing line against fellow motorists on your

local freeway you will pass most of them so long as you do not use cruise

control (which renders the racing line counterproductive).

The racing line is almost elegant the way Warhol

is almost elegant. Neither the racing

line nor Warhol is elegant as a Matisse line; the racing line and Warhol do

something worth doing more quickly than other approaches. The racing line kept through a full circuit

is nearer Matisse than Warhol came; Warhol was the racing line through a single

curve, maybe two. The Matisse line,

though, is the racing line taken through an unknown circuit drawn but a moment

before.

Tire, tiring, tired.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry