By Bart Barry-

CHARLOTTE – This city is its state’s largest by quite a bit, and some years ago the Associated Press offended Charlotteans, if not all Carolinians, by not-allowing this city to stand without its state’s abbreviation, “N.C”, so today we’ll remedy that if only because Charlotteans, if not all Carolinians, seem an increasingly prickly lot. This has naught to do with prizefighting but an explanation for why this column isn’t being written with its home byline on the first week in many it might’ve been.

Because Saturday in San Antonio the weekend’s biggest match happened at Alamodome – Tijuana’s Jaime Munguia stopping County Cork’s Gary “Spike” O’Sullivan – and I wasn’t there. But I was here, in North Carolina, and haven’t regrets about it, which is odd not because of Munguia-O’Sullivan but because of missing a chance to converse with Munguia’s chief second, Erik “El Terrible” Morales, who might well hold a fortuneteller’s insights for Munguia. As I once wrote quite a bit but stopped doing years ago, El Terrible is half the reason I began writing about our beloved sport 15 years ago, and his nemesis, Marco Antonio Barrera, is the other.

As El Terrible’s softened, rounded face flashed across DAZN’s broadcast I felt a quick if small pang of regret at being stationed 1,200 miles eastwards, a pang assuaged by a question like: What, actually, would you ask Morales? Not much. The last thing an interview should be is an exercise in thanking its subject for the joy he brought the interviewer, and so there are no regrets at missing a chance to converse with El Terrible.

What, then, might El Terrible fortunetell for Munguia?

“Just because you can no longer make junior-[weightclass] does not mean you are now a proper [weightclass].”

Munguia got the stoppage Saturday when an attritioned O’Sullivan relented too much and fell to the wrong side of the decisive point, yes, in a match well officiated by local referee Mark Calo-oy, but a quick glance at O’Sullivan’s face after being struck regularly by Munguia’s hooks and crosses for a halfhour and change tells you Munguia hasn’t brought the sum of his powers from 154 pounds to 160.

About 15 years ago, after losing a controversial decision to Barrera and winning an extraordinary fight with Manny Pacquiao (it would take seven years and 15 fights for anyone, much less Morales, to turn the feat again), Morales ate his way directly out of the super featherweight division and into a staybusy, vacant WBC International Light Title tilt with a featherfisted Philadelphia cutie named Zahir Raheem, who conclusively denuded El Terriblemente Gordo, stopped all his momentum and got him remanded to fatcamp by promoter Top Rank to prepare for consecutive knockout losses to Pacquiao and a definitive end to the serious part of Morales’ career.

Munguia is obviously in a different place in his career than El Terrible was back then, and very much younger in years and experience, but physical freaks who rely on freakish physicality do not age well, which is why an inability to scale a lower weight is verily the end of comparisons betwixt Munguia and his trainer – who was roughly thrice the boxer Munguia is.

Munguia has improved, though. His head movement is worth noting because head movement of any kind influences opponents disproportionately more than it looks to onlookers. Any head movement at all is multiples more effective than no head movement because it can stay an opponent’s combination fractionally long enough to cancel it altogether. At any level, but especially professional, boxing is a sport of rhythm and timing, and if you can make your attacker pause to reconsider, his reconsideration often as not becomes paralysis.

Coincidentally the way round this paralysis is an offensive quality Munguia also possesses, something like a burn-the-boats commitment to whatever combination one decided to throw before his opponent started moving about. When Munguia decides the time has come for 3-2-3 (hook/cross/hook) he throws it and keeps throwing it till he’s done. Why is this anything but stubborn and stupid? Because if you can start the third (or more-th) punch in a combination, you generally can land it. The reason most guys do not land the hook in the 1-2-3 or the cross in the 1-3-2 or the second hook in the (admittedly odd) 3-2-3 is because they abandon the combination after its first two punches miss. Munguia does not.

That’s a winning quality when you are the much larger man with the greater punch. Trouble is . . . well, you get the picture.

Let’s close with a few observations about what can best be called deep-red states, like this one and Texas, and deep-blue ones, like Massachusetts, these days. The red ones are moving at an accelerating pace towards unfriendliness.

I spent 10 days in North Carolina in 1995, and it was the friendliest place I’d ever been. I grew up in Massachusetts, 1974-1992, and it was the unfriendliest place I’ve ever lived. I moved to San Antonio in 2010, and it was the friendliest place I’ve ever lived. In the last three months I’ve returned to Massachusetts and North Carolina and found they’ve swapped places on the friendliness spectrum. And San Antonio is at best 30-percent friendly in 2020 as it was a decade ago.

Some of that is migration: The Northeast has exported its retirees to the taxfree South, flushing the toilet as it were, landing population density on cities whose infrastructures and mentalities were illprepared for it. But more of it, I suspect, is about what happens when a state goes halfassed libertarian, cutting funding for every social service save “public safety” – the population becomes fearful and tribal, regressing towards a downward spiral of selfjustifying desperation, wherein a fearful and less-productive populace sees its fears confirmed, over and over, and commits more and more of its dwindling budget to public-safety measures that do little but make its populace more fearful and less productive.

Finally, you get what you pay for.

*

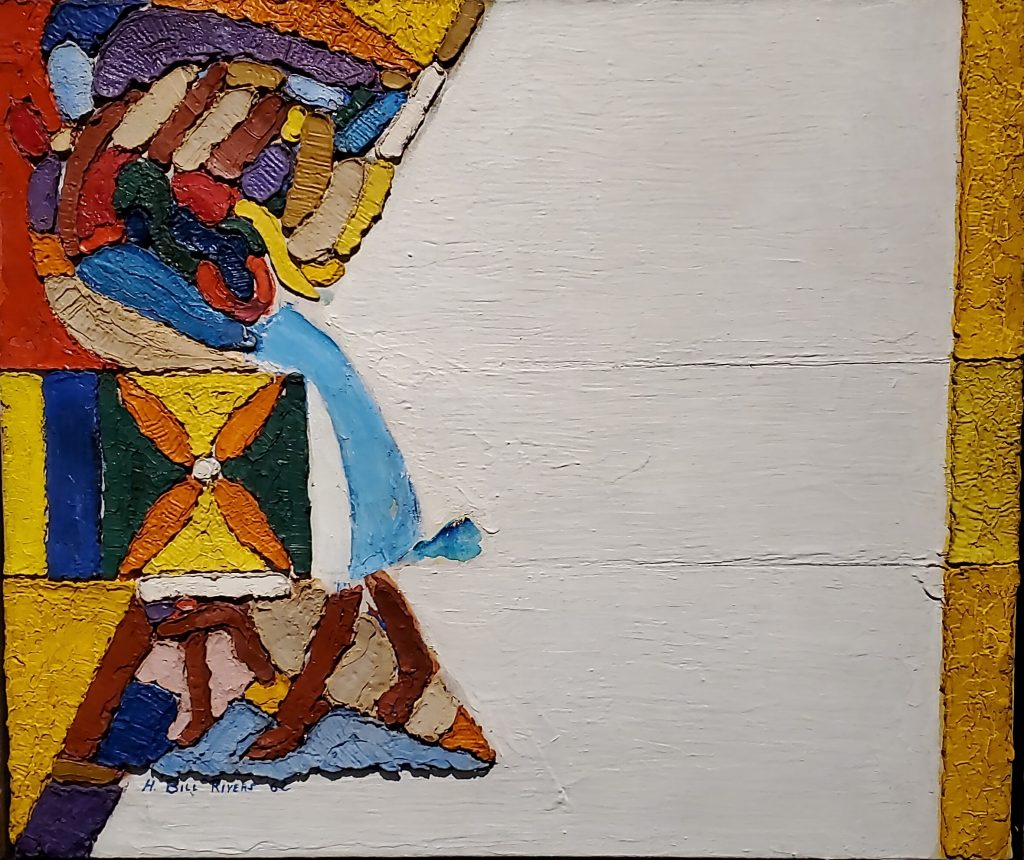

Editor’s note: The accompanying photograph is the painting “Dance Around a Flower” by North Carolina artist Haywood Rivers – part of an intriguing permanent collection at Mint Museum Uptown.

*

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry