By Bart Barry-

SAN ANTONIO – Friday afternoon, 10 miles southeast of here, restrictions got eased by local government and free COVID-19 testing became much more accessible at Freeman Coliseum – which shares a lot with its larger, more celebrated successor, AT&T Center, home of the Spurs.

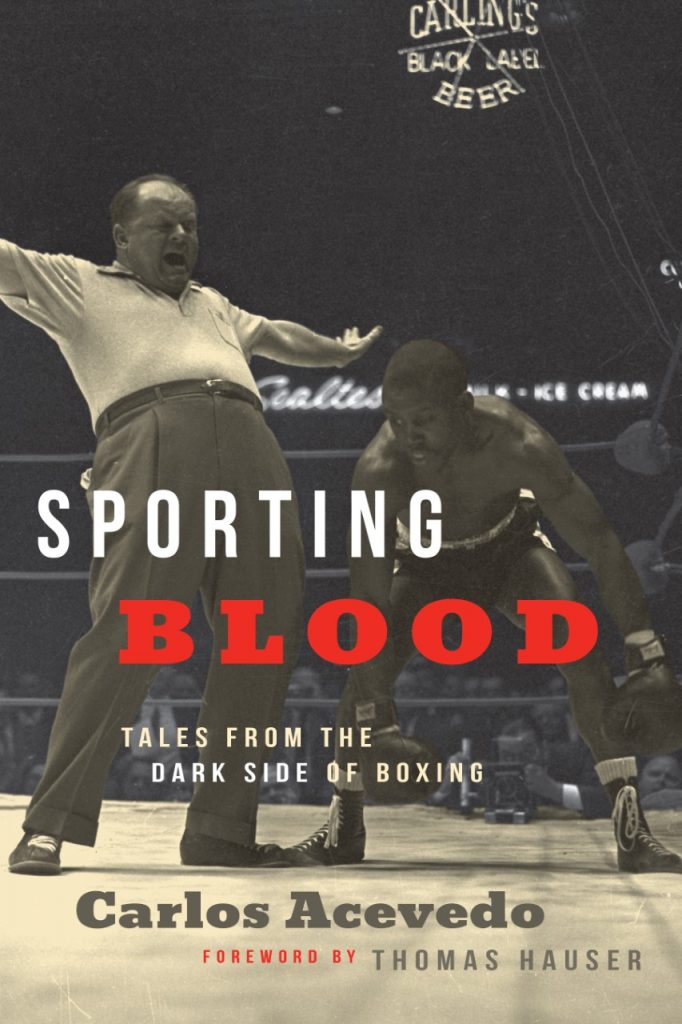

If you’re thinking, Freeman Coliseum, why, where have I read about that recently, here’s to hoping the answer is “Sporting Blood” (Hamilcar Publications, $27.95), Carlos Acevedo’s new book of “Tales from the Dark Side of Boxing” – in which Freeman Coliseum gets recalled more times than I can recall seeing it in any book I’ve read.

That last clause works well about a lot of items in Acevedo’s book, which is a clumsy way of imparting how damn original it is. Not gimmicky original, not look-at-me-I’m-writing original; proper original.

I’m going to let things go where they might from here, adopting a first-person style nearer what Thomas Hauser employs in “Sporting Blood’s” foreword, eschewing what straight, third-person boundaries Carlos sets for his art. Hauser and I came on Acevedo’s magnificent prose right about the same time in 2011. I’m sure I found TheCruelestSport.com via a Steve Kim tweet and knew within a paragraph how large Carlos’ talent was by the only indicator I trust: Envy.

Once you’ve decided you’re a writer you’ve unwittingly entered a competition with everyone you read henceforth, and reading, the deep pleasures of which first made you think about writing, changes and changes. You imitate your favorite writers, reading them more to write them better – like Ellison transcribing Hemingway – and they become your influences, and then you read their influences, and if all goes well you luck into Harold Bloom’s misprision. Along the way you start reading the seams of others’ writing, both in the way a couturier examines a dress and the way a major leaguer knows to lay-off a breaking ball. You see the dozens of decisions every author makes on every page, and how he executes them, and frankly it makes reading average writers a lot less fun.

But reading takes care of its own, and if you enjoy it enough to do it enough, reading leads you to the best writers, and their stitches are so tight, and they hide the ball so well in their windups, you transcend your pettiness and enjoy them much more than you could if you weren’t a writer. I thought about this a goodish bit by the midpoint of “Sporting Blood” – about just how much I was enjoying the experience of being immersed in Carlos’ world, however unpleasant he tries to make it. (There is no flimflamming in the book’s subtitle. More about that in a bit.)

Carlos writes in a masculine prose that is not macho. It knows what it is, has no compulsion to explain itself, feels effortless, knows where it’s going, and doesn’t compromise its style for others’ whims. Carlos himself is nearly unknowable in his writing and uncompromising.

Most of the authors to which Carlos Acevedo now will be compared had either great editing or incredible access and usually both. They worked at newspapers or magazines with full editorial staffs, sat a row or two from the canvas at every fight, and got to follow their subjects from training camps into dressing rooms and back to hotels. Carlos has matched or bettered them with a library card. That takes ambition, discipline and magic.

“In the years since his humiliating surrender to Sugar Ray Leonard in the infamous ‘No Mas’ debacle, Roberto Durán, formerly the most revered fighter in the world, had become little more than a pot-bellied barfly whose roadwork consisted of chasing women.”

That’s from “Yesterday Will Make You Cry” – a chapter about Davey Moore, not Roberto Duran, and it’s a good look at the craft one finds throughout the book. “Pot-bellied barfly” is both rhythmic and evocative, and wonderful for being unnecessary. It’s writing for those who love to read. Here’s some more:

“Although [Mike] Quarry never won a world title, he was surely the undisputed parking lot champion of the San Joaquin Valley. More than one poor schlub found himself, bridgework loosened, nose newly askew, laid out on some patch of concrete in Bakersfield, courtesy of a left hook that had failed to stop some of the best light heavyweights in the world but was more than enough for paunchy nightcrawlers who trained exclusively on Combos, Alabama Slammers, and Marlboros.”

That’s from “Lived Forward, Learned Backward” – a chapter about the Quarry Curse. The second sentence just goes on and on, reveling in its stamina. I was chuckling and shaking my head and thinking what the hell is Carlos doing? even before the “punchy nightcrawlers” showed up with their “Combos, Alabama Slammers, and Marlboros.”

This book is ever judgmental but never unsympathetic. It embraces the absurdity of its subjects’ lives the way many of them lived to do. And it’s joyful in its own immersion. “Total Everything Now” is an exquisite chapter, beginning with its title, about Mike Tyson’s 1988, peppered throughout with mentions of Tyson’s notorious mother-in-law, Ruth Roper. But not until the sixth allusion to Ruth (a feeling of pity, distress, or grief), a gratuitous parenthetical about her ubiquitousness on the chapter’s final page, do you realize Carlos has aptly and humorously used her name for seasoning throughout.

He does something similarly free-indirect with drugs in a chapter about Sonny Liston’s death, “Red Arrow”, named after “a bebop trumpeter nicknamed ‘The Red Arrow.’” Suddenly a hitherto-sober book fills with amphetamines, morphine, mushrooms, pot, LSD, horse, barbiturates, tranquilizers, reefer, coke, sniffing, shooting, skag, joypopping, and chasing the dragon.

Which at last brings us zigging and zagging to a theory about Acevedo’s choice of subject, “The Dark Side of Boxing”. The best writers want to be read creatively, and so here comes some creative reading:

In “Sporting Blood’s” final 10 pages one of Acevedo’s numerous and rich similes includes William S. Burroughs and his cut-up method (wherein Burroughs took linear stories, cut them to pieces, then reassembled them in nonlinear ways). Subsequently I spent Saturday reading “Naked Lunch” – Burroughs’ 1959 tale of debauchery – thinking about how Carlos tells his stories of Muhammad Ali (“A Ghost Orbiting Forever”), Aaron Pryor (“Right on for the Darkness”), Johnny Tapia (“Under Saturn”) and Tony Ayala Jr. (“The Lightning Within”). If one set out to use a cut-up style to describe actual prizefights, it mightn’t work; there are but eight punches in the boxing cannon, after all, and championship matches generally progress in an orderly if not predictable way. But if one wished to tell to-the-edge-of-panic tales of these men’s lives both before and after prizefighting . . .

*

CARSON, Calif. – Before Chocolatito got stretched by The Rat King, I flattened my left hand and set it at eye level then said to Sean Nam, a talented young boxing writer from New York, “Here’s Carlos.”

Then I set my right hand at chest level and said, “And here’s everyone else.”

*

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry