Writing for those who love to read

By Bart Barry-

SAN ANTONIO – Friday afternoon, 10 miles southeast

of here, restrictions got eased by local government and free COVID-19 testing

became much more accessible at Freeman Coliseum – which shares a lot with its larger,

more celebrated successor, AT&T Center, home of the Spurs.

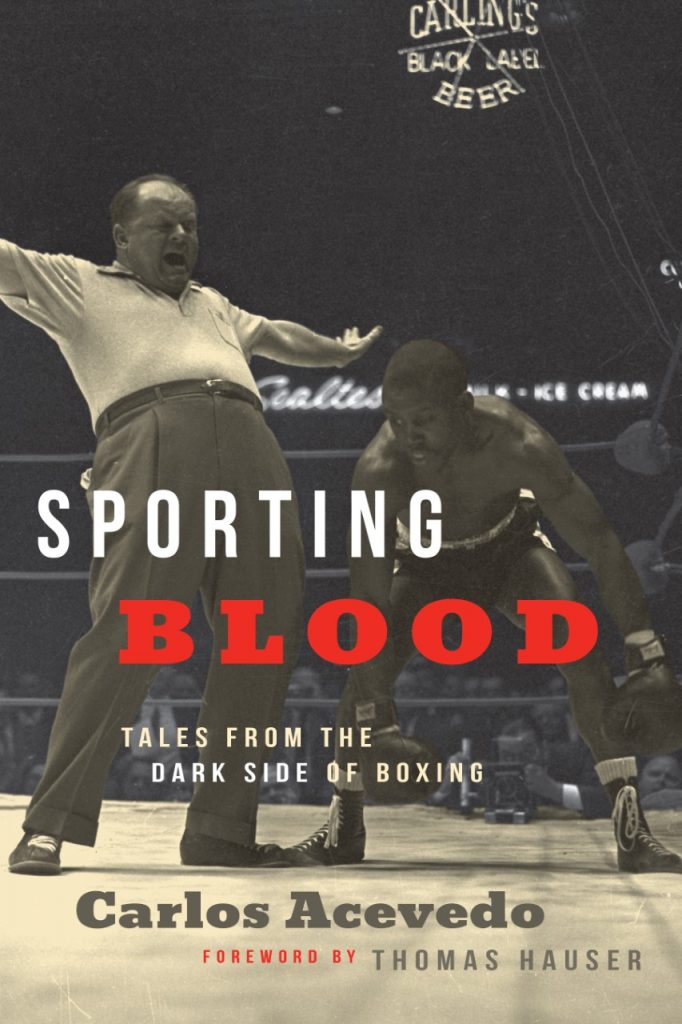

If you’re thinking, Freeman Coliseum, why, where

have I read about that recently, here’s to hoping the answer is “Sporting Blood”

(Hamilcar Publications, $27.95), Carlos Acevedo’s new book of “Tales from the

Dark Side of Boxing” – in which Freeman Coliseum gets recalled more times than

I can recall seeing it in any book I’ve read.

That last clause works well about a lot of items

in Acevedo’s book, which is a clumsy way of imparting how damn original it

is. Not gimmicky original, not look-at-me-I’m-writing

original; proper original.

I’m going to let things go where they might from

here, adopting a first-person style nearer what Thomas Hauser employs in

“Sporting Blood’s” foreword, eschewing what straight, third-person boundaries

Carlos sets for his art. Hauser and I

came on Acevedo’s magnificent prose right about the same time in 2011. I’m sure I found TheCruelestSport.com via a

Steve Kim tweet and knew within a paragraph how large Carlos’ talent was by the

only indicator I trust: Envy.

Once you’ve decided you’re a writer you’ve

unwittingly entered a competition with everyone you read henceforth, and

reading, the deep pleasures of which first made you think about writing,

changes and changes. You imitate your favorite

writers, reading them more to write them better – like Ellison transcribing

Hemingway – and they become your influences, and then you read their influences,

and if all goes well you luck into Harold Bloom’s misprision. Along the way you start reading the seams of

others’ writing, both in the way a couturier examines a dress and the way a

major leaguer knows to lay-off a breaking ball.

You see the dozens of decisions every author makes on every page, and

how he executes them, and frankly it makes reading average writers a lot less

fun.

But reading takes care of its own, and if you

enjoy it enough to do it enough, reading leads you to the best writers, and their

stitches are so tight, and they hide the ball so well in their windups, you

transcend your pettiness and enjoy them much more than you could if you weren’t

a writer. I thought about this a goodish

bit by the midpoint of “Sporting Blood” – about just how much I was enjoying

the experience of being immersed in Carlos’ world, however unpleasant he tries

to make it. (There is no flimflamming in

the book’s subtitle. More about that in

a bit.)

Carlos writes in a masculine prose that is not

macho. It knows what it is, has no

compulsion to explain itself, feels effortless, knows where it’s going, and doesn’t

compromise its style for others’ whims.

Carlos himself is nearly unknowable in his writing and uncompromising.

Most of the authors to which Carlos Acevedo now will

be compared had either great editing or incredible access and usually

both. They worked at newspapers or magazines

with full editorial staffs, sat a row or two from the canvas at every fight,

and got to follow their subjects from training camps into dressing rooms and

back to hotels. Carlos has matched or

bettered them with a library card. That

takes ambition, discipline and magic.

“In the years since his humiliating surrender to

Sugar Ray Leonard in the infamous ‘No Mas’ debacle, Roberto Durán, formerly the

most revered fighter in the world, had become little more than a pot-bellied

barfly whose roadwork consisted of chasing women.”

That’s from “Yesterday Will Make You Cry” – a

chapter about Davey Moore, not Roberto Duran, and it’s a good look at the craft

one finds throughout the book.

“Pot-bellied barfly” is both rhythmic and evocative, and wonderful for

being unnecessary. It’s writing for

those who love to read. Here’s some

more:

“Although [Mike] Quarry never won a world title,

he was surely the undisputed parking lot champion of the San Joaquin

Valley. More than one poor schlub found

himself, bridgework loosened, nose newly askew, laid out on some patch of

concrete in Bakersfield, courtesy of a left hook that had failed to stop some

of the best light heavyweights in the world but was more than enough for

paunchy nightcrawlers who trained exclusively on Combos, Alabama Slammers, and

Marlboros.”

That’s from “Lived Forward, Learned Backward” – a

chapter about the Quarry Curse. The

second sentence just goes on and on, reveling in its stamina. I was chuckling and shaking my head and

thinking what the hell is Carlos doing? even before the “punchy

nightcrawlers” showed up with their “Combos, Alabama Slammers, and Marlboros.”

This book is ever judgmental but never

unsympathetic. It embraces the absurdity

of its subjects’ lives the way many of them lived to do. And it’s joyful in its own immersion. “Total Everything Now” is an exquisite

chapter, beginning with its title, about Mike Tyson’s 1988, peppered throughout

with mentions of Tyson’s notorious mother-in-law, Ruth Roper. But not until the sixth allusion to Ruth (a

feeling of pity, distress, or grief), a gratuitous parenthetical about her

ubiquitousness on the chapter’s final page, do you realize Carlos has aptly and

humorously used her name for seasoning throughout.

He does something similarly free-indirect with

drugs in a chapter about Sonny Liston’s death, “Red Arrow”, named after “a

bebop trumpeter nicknamed ‘The Red Arrow.’”

Suddenly a hitherto-sober book fills with amphetamines, morphine,

mushrooms, pot, LSD, horse, barbiturates, tranquilizers, reefer, coke, sniffing,

shooting, skag, joypopping, and chasing the dragon.

Which at last brings us zigging and zagging to a

theory about Acevedo’s choice of subject, “The Dark Side of Boxing”. The best writers want to be read creatively,

and so here comes some creative reading:

In “Sporting Blood’s” final 10 pages one of

Acevedo’s numerous and rich similes includes William S. Burroughs and his cut-up

method (wherein Burroughs took linear stories, cut them to pieces, then

reassembled them in nonlinear ways). Subsequently

I spent Saturday reading “Naked Lunch” – Burroughs’ 1959 tale of debauchery –

thinking about how Carlos tells his stories of Muhammad Ali (“A Ghost Orbiting

Forever”), Aaron Pryor (“Right on for the Darkness”), Johnny Tapia (“Under

Saturn”) and Tony Ayala Jr. (“The Lightning Within”). If one set out to use a cut-up style to

describe actual prizefights, it mightn’t work; there are but eight punches in

the boxing cannon, after all, and championship matches generally progress in an

orderly if not predictable way. But if

one wished to tell to-the-edge-of-panic tales of these men’s lives both before

and after prizefighting . . .

*

CARSON, Calif. – Before Chocolatito got stretched

by The Rat King, I flattened my left hand and set it at eye level then said to Sean

Nam, a talented young boxing writer from New York, “Here’s Carlos.”

Then I set my right hand at chest level and said,

“And here’s everyone else.”

*

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry