By Bart Barry-

The doldrums are upon us. Winter is come. While cable news broadcasts the final hours of America’s worst president, Netflix serially releases serial-killer biopics, and prizefighting hibernates, an interesting new movie related to an important 1964 championship match got released last week and might deserve some of your time this Martin Luther King Day.

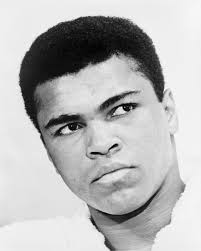

Some years Muhammad Ali’s birthday falls on Martin Luther King Day. This year it fell the day before. They were contemporaries in the sense of sharing the world stage but were not known to be confidantes, and King was 13 years older than Ali.

Nine years ago I wrote a piece for The Ring about Ali turning 70. It gave me an occasion to research King, and that research brought me to recordings of his speeches. I recommend revisiting them. His talent for speechmaking was enormous, many times that of today’s American leaders’, up to and including Barack Obama. There’s a majesty to King’s delivery that has yet to be matched. Even with 57-year-old acoustics, outdoors, King’s voice is unmistakable and gigantic.

I thought about King and the mythology of Ali, too, last weekend while watching One Night in Miami, a Regina King film adapted from Kemp Powers’ 2013 play and recently released on Amazon Prime. It is an excellent movie, finally, that begins badly. Even without seeing the play or reading its script an attentive viewer shouldn’t have trouble spotting what is theatrical and what is cinematic, what got created by a talented young playwright and what puerile exposition got added for marketing reasons.

The clunky introductions to Ali, Sam Cooke, Jim Brown and Malcolm X are very much Hollywood claptrap, turning the caricature knob to 10, and one fears many viewers who watch its preview or opening 15 minutes will never go any further. If you’re reading this, though, consider it a recommendation for getting through the throat-clearing and into the motel room where much of the movie and all its best writing, in the room and especially on its rooftop, happens. The acting, too, is excellent.

Despite the night in the movie’s title belonging to Ali, the movie is not about Ali or Cooke or Brown nearly so much as Malcolm X. When the other characters are not talking to Malcolm X they’re talking about him. This is not hagiography, which is why the movie works so well. Malcolm X gets accused of being a manipulator and a parasite and simply a man without a job. If he isn’t surly he is generally joyless, a scold.

The other three men are nearer their primes; Ali the newly crowned king of prizefighting, Brown the greatest football player of all time, Cooke about to record “A Change is Gonna Come”. Malcolm X is less than a year from his assassination and aware the consequences of his planned departure from Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam, which Malcolm X formally departed 11 days after Muhammad Ali beat Sonny Liston in Miami.

One of the sadder passages in Malcolm X’s autobiography, a book I read during Christmas break my senior year in high school, decades before “woke” was a word, comes when Malcolm X describes a chance encounter in an airport with Ali. Both men know they are to remain separated. Malcolm X portrays their estrangement as a personal tragedy.

Watching One Night in Miami, it is easy to see why. Cassius Marcellus Clay, as played adeptly by Canadian actor Eli Goree, is an enchanting energy to be around. Childlike and often childish Goree’s Clay is a gifted young man gliding through life without an inkling what difficulties lie in wait and without very much patience yet for others’ difficulties. Goree’s Clay is also better than Will Smith’s.

While a large part of the movie’s plot treats Clay’s pending conversion to Islam, or its announcement anyway, the movie’s best parts do not include Clay as more than an observer. Malcolm X’s relationship with Sam Cooke, their mutual antagonism and love, as depicted by Kingsley Ben-Adir and Leslie Odom, brings the story’s most poignant scenes.

Ben-Adir’s portrayal of Malcolm X brought to mind master literary critic James Wood’s observation that in the Gospels Jesus weeps but never laughs – so much to mind that I misplaced an hour trying to find a New Yorker article in which Wood compares the messianic ascents of Jesus and Malcolm X. Turns out, that interesting comparison belongs to a different literary critic, Adam Gopnik.

The movie ends with Cooke, having been sparked by Bob Dylan and antagonized by Malcolm X’s praise of Dylan, making a debut of his new, more-conscious song. Then Clay becomes Muhammad Ali and Jim Brown becomes an actor and Malcolm X’s house gets firebombed. Before the credits roll there’s a footnote about Malcolm X’s assassination though no mention of Cooke’s death two months before.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry