Editor’s note: For Part 1, please click here.

***

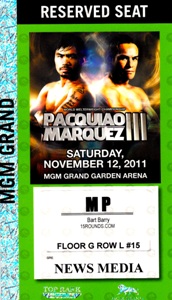

The day Manny Pacquiao and Juan Manuel Marquez fought their rubber match in November 2011, Las Vegas gazed upon its empty MGM Grand Garden Arena for most of the undercard matches because that is what it does. Friday weigh-ins are for serious fans. Saturday nights sadly are not.

Pacquiao fought Marquez a third time for several reasons. Marquez had traversed the Philippines immediately after their second match, one whose official decision went to Pacquiao and unofficial decision went mostly to Marquez, chiding the Filipino hero, and Pacquiao wanted to end that for posterity’s sake. The other idea was that Marquez, an all-time great featherweight-cum-lightweight, would, at welterweight, make an excellent scalp to toss on the table when negotiations for Pacquiao-Mayweather returned: Not only is Manny a bigger pay-per-view draw, but he obliterated Marquez the way Mayweather could not.

Marquez’s class and pride were such that nobody would blow through him. Not at 126 pounds, not at 143. Pacquiao was a whirligig of oddly canted aggressiveness, one that loudly struck opponents from angles that surprised other prizefighters and made commentators ecstatic. Marquez had no such flair but greater audacity. Where Pacquiao threw jab, jab, leaping cross, Marquez threw uppercut leads, moving forward, in world championship prizefights – just about the ballsiest thing a man can do.

Marquez’s greatness as a counterpuncher, the quality that made his violent defeat essential to the Pacquiao résumé, was too large, finally, and cast shadows on the subject it was there to brighten.

*

The day Manny Pacquiao and Juan Manuel Marquez fought their rubber match in November 2011, Las Vegas shined and sparkled with its usual charm and timeless (clock-less) efficiency. Put everyone off schedule, the city plotted, then charge them to catch up.

Pacquiao had not improved a fraction so much as his publicists declared. A coming documentary about his trainer put a burden on Pacquiao’s technical improvement. If, after all, Pacquiao were but a hyperagressive southpaw who won with activity more than class, any monuments erected to his and his trainer’s greatness would come under scrutiny. Deeply interested parties, then, declared Pacquiao’s technical imperfections innovative, rather than call them what they were: a regression to form.

By the ninth round of his rubber match with Marquez, Pacquiao was aware of his technical inadequacy. He fooled Marquez less this time than the previous two because Marquez promised his trainer he would not look for a knockout and wander into what maniacal exchanges Pacquiao always won. If Pacquiao won his third fight with Marquez, he did it the brute’s way and was simply busier.

A compliant and unimaginative print media paused for a moment at what it saw in rounds 7-11, got the judges’ confirmation all was actually well, and went back to his its prefight narrative. Maybe Marquez did better than expected, perhaps the fight could be called a draw, but, ah, for not closing the show, Marquez did not deserve to win.

No one was fooled, but deadlines were not missed either.

*

The day Manny Pacquiao and Juan Manuel Marquez fought their rubber match in November 2011, Las Vegas assured the country it was not in hard a place as Detroit or New Orleans, the country’s other two depressed cities. Vegas was back, baby! Look at the room prices.

The American economy was rebounding, too. Perhaps growth was illusory, maybe underemployment was nearing record levels, but the job creators were getting some of their wealth back, and that would trickle down to the rest of America eventually. Yes, idiot, it would; didn’t you know anything about economics?

The media area at MGM Grand Garden Arena had the usual dynamic. The first five rows of tables were a cutthroat assembly of the names everyone knew, with most working on deadlines, their laptop monitors guarded closely as poker hands. Then came the girlfriends of Spanish- and Tagalog-language network executives. In the back were the online and magazine writers whose names you didn’t know. They were the most convivial bunch – happy to help one another with the result of the fourth undercard bout or a recollection of that time, somewhere in Mexico, the press had to stand and hold their seats overhead because cups of beer and urine rained on them.

Some of the guys in the back had scored the second half of the fight a whitewash for Marquez and were happy for the Mexican great, happy he might finally have his due, whatever the consequences. Those guys wore stunned, betrayed looks as they shuffled off to the postfight press conference where Pacquiao would have time for only two questions because it was getting late.

*

The day Manny Pacquiao and Juan Manuel Marquez fought their rubber match in November 2011, Las Vegas did the existential dance entrepreneurs often do, promising things were good as they’d ever been, might even be better, sales were up – while expecting others to cheer its fortune-seeking with the same enthusiasm it did.

Nacho Beristain told Marquez he had the fight won during the championship rounds for a couple reasons. As a sculptor of 16 world champions Beristain knew what his eyes told him and hadn’t a doubt his man was winning. And Beristain knew with mathematical certainty Marquez would have been 2-0 against Pacquiao were it not for those four knockdowns in their first two tilts, and then there would have been no reason for a rubber match, or the Pacquiao legend.

After the initial disgust of the 116-112 card wore off and we settled into writing our fight reports, the photocopied scorecard tallies got handed out. When it was revealed Judge Glenn Trowbridge saw Marquez win the 12th round but not the eighth, ninth, 10th or 11th, a secondary, harder-to-dismiss disgust set in.

*

The day Manny Pacquiao and Juan Manuel Marquez fought their rubber match in November 2011, Las Vegas marched on. “See you in May!” it said, with a big grin.

The umbrage passed. Pacquiao lost a few fans. His myth lost genuine and serious-minded advocates, the sort of men who write history. Marquez gained a few fans and returned to Mexico, assured in his greatness. The umbrage passed.

I was in Houston the following week to cover Julio Cesar Chavez’s son and had already forgotten a large part of what happened at 2011’s biggest fight.

Bart Barry can be reached at bart.barrys.email (at) gmail.com