Marquez masters Pacquiao but not judges in third match

LAS VEGAS – In the years since Manny Pacquiao and Juan Manuel Marquez began their rivalry, fans have debated what might have happened had Pacquiao not felled Marquez four times with left hands in the men’s first two fights. Saturday, they found out. But somebody forgot to tell the judges.

In a fight at MGM Grand likely to be remembered for Marquez’s technical mastery of Pacquiao through its second half, Pacquiao inexplicably prevailed by majority-decision scores of 114-114, 115-113 and 116-112.

The 15rounds.com ringside card did not concur, scoring the fight a clear victory for Marquez, 117-113.

After four uneventful but even rounds, 12 minutes in which each fighter showed the other perhaps too much respect, Pacquiao (54-3-2, 38 KOs) and Marquez (53-5-1, 39 KOs) began to exchange in round 5, with Marquez throwing left-uppercut leads Pacquiao surely had not seen in training-camp sparring sessions. Marquez also kept Pacquiao off-balance and somewhat confounded by his counter movement and patience.

Through the fight’s midway point, only round 5 had been decisive for either fighter. That round went Marquez’s way.

By the end of round 8, it had become apparent that Marquez understood Pacquiao better than Pacquiao understood Marquez, and that if Marquez could stay fresh and away from the left hand, he’d have the fight won. In the ninth, the fight’s best round to that point, Marquez appeared to expose the myth of Pacquiao’s improved footwork, causing the Filipino champion to swim at him, flailing wildly with both hands.

As each round passed, it became more apparent that uneventful rounds should be scored in Marquez’s favor for demonstrating the Mexican’s superior ring generalship.

Heading into the championship rounds, Pacquiao still did not have a solution for Marquez’s left uppercut lead, but Marquez had picked up every Pacquiao left cross and slipped it or ducked it, sending Pacquiao careening over his lead shoulder. As the fight ended, Marquez triumphantly raised his fist while Pacquiao turned and walked slowly away.

After the judges’ scorecards were read, fans’ disapproval grew so loud that Pacquiao’s voice could not be heard over the roar, and Pacquiao’s postfight interview yielded no new insights.

TIMOTHY BRADLEY VS JOEL CASAMAYOR

While most fights open with a contest between combatants to see who can establish his jab, California junior welterweight Timothy “Desert Storm” Bradley’s match with Cuban Joel Casamayor began with a contest to see who could establish the head.

And so it went in Saturday’s co-main event, a fight for Bradley’s titles and a foul-fest that was every bit as ugly as boxing insiders, and even outsiders, expected it to be. Referee Vic Drakulich earned his pay, warning Casamayor (38-6-1, 22 KOs) repetitively for butts and low blows and presiding over an aesthetically displeasing fight in which Bradley (28-0, 12 KOs) eventually prevailed by corner-stoppage TKO at 2:59 of round 8.

From the opening bell, Casamayor pursued a prefight strategy that could best be classified as slip-butt-hold, establishing his bald head as his best weapon. Bradley, who has often and somewhat unfairly been classified as a dirty fighter, held his own head high, keeping Casamayor at a safe distance and whacking him with accurate right hands.

The match’s result was never in doubt – with Bradley too active and Casamayor too old – which left lots of room for doubt as it concerned the making of Bradley-Casamayor in the first place. Matched correctly and given a chance by fans, Bradley could likely be a star in one of boxing’s best divisions. Matched against a cagey Cuban against whom no one has ever looked particularly good, and fighting before a partisan Filipino and Mexican crowd, Palm Springs’ Bradley had little chance to win new fans for himself.

MIKE ALVARADO VS. BREIDIS PRESCOTT

Coloradoan “Mile High” Mike Alvarado, long seeking a career-defining win that would make him popular as his undefeated record says he should be, might have gotten just such a win against Colombian Breidis Prescott.

Appearing to trail by a significant margin in the match, Alvarado (32-0, 23 KOs) rallied in the final round to bludgeon an exhausted Prescott (24-4, 19 KOs) with ferocious uppercuts till referee Jay Nady stopped the match, awarding Alvarado a knockout victory at 1:53 of round 10.

After giving away most of the match’s opening four rounds, Alvarado was bleeding from his nose, right eye and mouth but still marching forward, undissuaded, by the end of the fifth. Rounds 5 and 6 were the best Alvarado put together to that point in the match, and Prescott began to evince fatigue, fighting within Alvarado’s range and backpedaling awkwardly, after the fight’s midpoint.

Rounds 8 and 9 saw Prescott regain his stamina and reestablish distance, outboxing the heavier-punching Alvarado, who appeared at times to be fighting as if protecting a lead. But then the 10th round struck and Alvarado went for broke, leveraging uppercuts that completely changed the fight and kept him unbeaten.

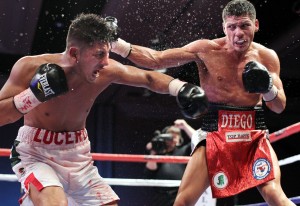

JUAN CARLOS BURGOS VS. LUIS CRUZ

The first televised fight of Saturday’s undercard, Puerto Rican lightweight Luis Cruz (19-1, 15 KOs) against Mexican Juan Carlos Burgos (28-1, 19 KOs), featured two guys who appeared to want to fight each other quite desperately but just never found the rhythm needed to turn the trick.

Although caught by a number of clean punches during the 10-round match, Burgos nevertheless prevailed by majority-decision scores of 91-95, 97-93 and 98-92, in a fight with numerous tough-to-score rounds.

DENNIS LAURENTE VS. AYI BRUCE

After six rounds of even if not particularly enthralling combat, Filipino Dennis Laurente’s (38-3-4, 20 KOs) undercard match with New York’s Ayi Bruce (13-5, 6 KOs) ended abruptly with a perfectly leverage left cross from the Filipino southpaw that ended Bruce’s night. Laurente’s left-handed lightning struck with effect enough to score Saturday’s first knockout at 0:57 round 7.

JOSE BENAVIDEZ VS. SAMMY SANTANA

Phoenix super lightweight Jose Benavidez may well represent promoter Top Rank’s best shot at a superstar for the year 2020, but he is not there just yet.

Against tough but limited Puerto Rican Sammy Santana (4-5-2), Benavidez (14-0, 12 KOs), who hurt both hands during the match, moved well and struck hard but was unable to stop Santana despite dropping him three times in the fight’s opening two rounds and winning a decision all three judges scored 60-50. Benavidez, whose lanky frame and perilous right cross are a little reminiscent of a young Thomas Hearns’, still relies on reflexes too much – often dropping his hands and pulling his head back from punches, in an amateurish maneuver that needs to be remedied.

VICTOR PASILLAS VS. JOSE GARCIA

Saturday’s second bout featured a battle of California featherweights in a four-round match between Victor Pasillos (1-0) of East Los Angeles and Jose Garcia of King City (0-4). Pasillos prevailed in his professional debut by three, one-sided scores of 40-36.

FERNANDO LUMACAD VS. JOSEPH RIOS

Latino versus Filipino, the ethnic theme for Pacquiao-Marquez III, began with an entertaining and competitive eight-round scrap between Philippines super flyweight Fernando Lumacad (25-3-3, 12 KOs) and Texan Joseph Rios (10-6-2, 4 KOs). Lumacad prevailed by unanimous decision scores of 77-73, 77-74 and 78-72.

The match began uneventfully, with neither fighter risking much of himself in the opening five minutes. With little time remaining in round 2, though, Lumacad caught Rios with what appeared to be a balance-shot left hook that sent Rios stumbling straight-legged to a far corner. In round 5, Lumacad dropped Rios a second time. But in the three rounds that followed, Rios fought back admirably, even winning the sixth on two of the official judges’ three cards.

Opening bell rang on Saturday’s card at 3:23 PM local time.

Photos by Chris Farina / Top Rank