A Terrible difference

A suspicion was confirmed Saturday. No, it wasn’t the suspicion we all harbored about Erik “El Terrible” Morales’ shopworn frailty. Morales’ comportment in the main event of “Action Heroes” was first rate. Rather, the suspicion was that this new generation of fighters, while competitive and proud, is not what the last generation of fighters was.

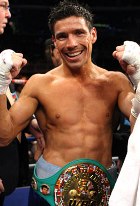

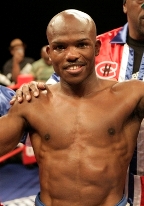

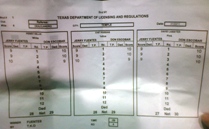

Argentine junior welterweight Marcos Maidana whacked and plowed his way to a majority decision against Morales – Mexico’s former super bantamweight, featherweight and super featherweight world champion – at MGM Grand in a fight broadcast on HBO pay-per-view Saturday. Maidana won by scores of 116-112, 116-112 and 114-114.

My scorecard went 118-113 for Maidana. I had the Argentine winning rounds 1, 3, 4, 6, 9, 11 and 12. I had Morales winning rounds 5 and 8. I had rounds 2, 7 and 10 even. If those even rounds all went Morales’ way, as many an “Action Heroes” viewer saw them, I still had Maidana winning 7-5.

A word or two about “Action Heroes” viewers. They were, almost to a man, advocates. It was not possible to buy the card without a zealous belief in “El Terrible.” Those who’ve shown Morales their zeal through the years were rewarded Saturday, they were vindicated Saturday, and they were thrilled Saturday. But they were not objective Saturday.

All paeans to punch accuracy and effect aside, Morales had rounds in which he landed fewer than 10 meaningful blows. Maidana was not in Morales’ class but was ineffectively aggressive throughout. And if you want boxing to entertain, you present scorecards that value ineffective aggressiveness over any criterion but its effective cousin.

If there was a loser Saturday it was not Morales or Maidana – though Maidana’s terrifying mystique was eroded. Instead, the losers were a new generation of fighters in general and two prizefighters in specific.

Those two prizefighters are Victor Ortiz and Amir Khan. Ortiz wilted and quit under Maidana’s assault 22 months ago then informed Staples Center patrons he should not have to endure an assault like Maidana’s. Khan then spent six minutes shamelessly fleeing Maidana in December while successfully defending his WBA 140-pound title in a performance for which he was lauded.

How does that performance look today?

While you consider that, consider this: Erik Morales, a 34-year-old veteran of 57 prizefights who retired almost four years ago and met Maidana 14 pounds above his prime fighting weight, just acquitted himself more nobly than Khan and Ortiz combined. And he did it with one eye.

The punches with which Maidana struck Morales – the same blows that still wake Ortiz and Khan with nightmares – had nary an effect on Morales who, after having his right eye shuttered by a left uppercut in round 1, did not wobble, run or signal for a doctor in the 33 minutes that followed.

That an overweight, overaged guy unable to see a left hook for 11 rounds just beat back the most-feared puncher in boxing’s most-competitive division does not speak well of our sport’s new generation. Not well at all.

And beat him back, Morales did.

The opening round saw Maidana’s relentless and undisciplined attack land all over Morales’ body, causing HBO commentator Jim Lampley to call Morales, quite rightly, a “shell” of his former self.

Maidana raced out his corner and whacked away at Morales spinning the former champion making him look poorly balanced and fragile bruising him with huge shots and rendering his right eye useless with a ferocious inside uppercut that nearly signaled the end.

But Morales knew the storm would subside. He had been across from men just as determined and feral as Maidana. And those men had twice Maidana’s class and savvy. Morales returned fire with three-punch combinations. He watched Maidana stumble and play motorboat while breathing.

Maidana never got comfortable as he’d planned because he was unable to chase Morales bullying him hitting him making him reel and retreat or skip sideways desperately – Maidana was unable to relax because he was across from a man who was not intimidated by him in the slightest a man whose fear of being struck by Maidana dissipated with each Maidana strike.

Then Morales buckled Maidana with a naked left hook lead. Morales was too old to hit Maidana with combinations half as intricate as he’d thrown a decade ago. But Morales still forced Maidana backwards and made the Argentine’s eyes grow with surprise and worry.

Maidana deserved to win for approaching the championship rounds with more self-belief than he deserved to carry charging after Morales reminding the crafty Mexican of the seven-year difference in their ages.

But Morales’ severe arrogance was not diminished. A half hour of combat with Maidana served only to remind him of his greatness.

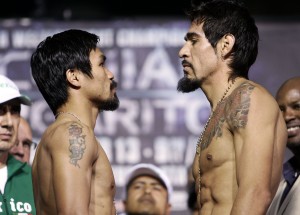

Who were the winners Saturday? Maidana, for having his hand raised. Morales, for burnishing his legacy at age 34 in a way he could not at age 30. Morales’ generation of fighters, generally. And Manny Pacquiao, specifically.

If you did not watch Morales in his middle rounds with Maidana and think of Pacquiao, you were not watching creatively enough. Morales threw half as many punches at Maidana, coming off the ropes, as he’d thrown at Pacquiao. And Maidana retreated, held or pushed his head under Morales’ chin. One-one-two from Morales made Maidana pause. One-one-two, one-one-two from Morales made Pacquiao bang his hands together and hurl himself on Morales like a doberman on a t-bone. Pacquiao twice slashed to the canvas, at 130 pounds, a man Maidana could not affect at 140.

Let us have no more loose talk of greatness, then, about today’s junior welterweight division. They are a good if coddled lot. They are not worthy of comparisons to men like Morales, Pacquiao, Juan Manuel Marquez or Marco Antonio Barrera.

They have dignity and heart, yes. But they do not have “dignidad y corazón” – not the way Morales used those words Saturday.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter: @bartbarry