What I did with $8 on Saturday instead of paying $44.95 for “200”

SAN ANTONIO – There was an excellent festival here called “Jazz’Salive,” downtown, Saturday. Some rain and lots of clouds, too. The rain was unwelcome but the clouds weren’t. No charge, though. Anyone who followed his ears to Travis Park got free jazz. And while that happened, a half mile down West Travis Street a whole lot of boxing happened for only $8 more.

That’s why it was so easy to forgo “200” later that night.

For a little less than 1/6 the price of “200: Celebrate and Dominate,” a four-fight Golden Boy Promotions pay-per-view card that certainly should not have been, a boxing fan round here could see 30 amateur bouts in a club show presented at San Fernando Gym by the South Texas Amateur Boxing Association.

The name of Saturday’s other card referred to the 200-year anniversary of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla’s famous “Grito” of death to the Gachupines and long life for the Virgin of Guadalupe. The shout launched Nueva España’s battle to become México and sufficed for 100 years till something like a Mexican civil war, oddly called “La Revolución,” led to another anniversary and sundry schoolhouse-renaming efforts.

San Antonio Parks and Recreation’s card featured more than a few kids whose lineage traces back to Spanish rule, too. Most names on the bout sheet that didn’t end in ‘s’ or ‘z’ went Guajardo or Garcia.

San Fernando Gym, itself, had a celebratory feel. Or maybe that was just the air conditioning. Some members didn’t know the basement could boast temperatures below 100 degrees; a heater blows year-round at the gym, even when it’s 95 outside. There was yellow tape across the heavy bags, and the speed bags, slip bags and double-end bags were in storage. In their stead were hundreds of aluminum folding chairs, convenient if not comfortable for five hours of boxing.

And it’s boxing, not fighting, by the way. The distinction is often a pedantic one, but there is a difference. Amateurs are boxers that outpoint one another in bouts. Professionals are prizefighters that hurt one another in fights.

There are some other differences. Amateurs wear headgear and heavy gloves and punch for shorter durations. Fatigue takes its same effect, though. That’s where it gets interesting. If you have less time and fewer means of inducing fatigue in your opponent, what do you do? Try harder. That means more punches and less defense. And that means quicker pace.

Quicker pace than, say, Saul “Cinnamon” Alvarez and Carlos Baldomir? Indeed. That fight on the “200” card featured an under-proven Mexican hopeful and a worn-out Argentine, and opening reviews were not positive. Then Alvarez stretched the hard-headed former welterweight champ, and hope was restored.

Alvarez is not the next great Mexican prizefighter. But he’ll suffice until Bob Arum finds him.

Hundreds of punches fly every couple of minutes in an amateur bout. Knockouts are few. Not many kids have the skill or strength to render another boxer unconscious. Too, there is a focus on process – one kid was penalized twice Saturday because his mouthpiece protruded – as much as on winning. And that’s a good way to build upstanding citizens if not future prizefighters.

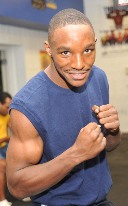

Even with all the extra cushioning, though, future stars separate themselves. Saturday, that was Jairo Castaneda – a San Fernando product who knocked his opponent out hard. You can tell right away; some kids have a certain poise, regardless of fighting style. It’s impossible to fake. Castaneda measured his opponent for a round then exploited his every weakness.

Sounds like Victor Ortiz did the same thing to “Vicious” Vivian Harris in Staples Center later on. Good. Harris should not have been allowed back in a prizefighting ring after the stunt he pulled in Tucson 13 months ago. Realizing Mexican Noe Bolanos was going to beat him, Harris used an accidental collision of heads to fake a brain injury. His gurney ride from the ring actually drew taunts from the crowd at Desert Diamond Casino. When have you ever heard a gurney booed?

Worse yet, out of concern for Harris’ health we spiked a great lead that night:

“Vivian Harris entered the ring wearing ‘Vicious’ as his nickname and ‘Sugar Factory’ on the back of his trunks. The trunks won.”

That brings us to the Saturday bout that, for personal reasons, comprised the most interest: San Fernando’s Jimmy Martinez Jr. against Cutting Edge’s Henry Arredondo in a 119-pound bout of three, 90-second rounds. See, Jimmy Jr. and his father Jimmy Sr. train every weeknight at San Fernando. And they are a picture of class.

“I’m teaching him boxing because that’s what I know,” says Jimmy Sr., once a local amateur standout. “If I knew tennis, I’d teach him tennis.”

He’s also going to have to teach him not to cock his jab before throwing it. Arredondo read this hitch in Jimmy Jr.’s swing early and managed to slip every jab thrown his way. Still, the bout was excellent and worth the wait. And that’s saying something about less than five minutes of boxing that came in a card’s 325th minute.

Anyone think the main event of “200” was worth the wait? Then forgive but don’t forget. That goes for Golden Boy Promotions, of course, but more for HBO – who lent its dwindled credibility to the card.

Oh, let me guess. If it weren’t for pay-per-view, Shane Mosley and Sergio Mora would have had to split the gate – a fraction of their Saturday purses – and those of us not in Los Angeles would have missed the chance to see them. Such a bad deal?

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter.com/bartbarry