One aficionado’s return to Showtime Boxing

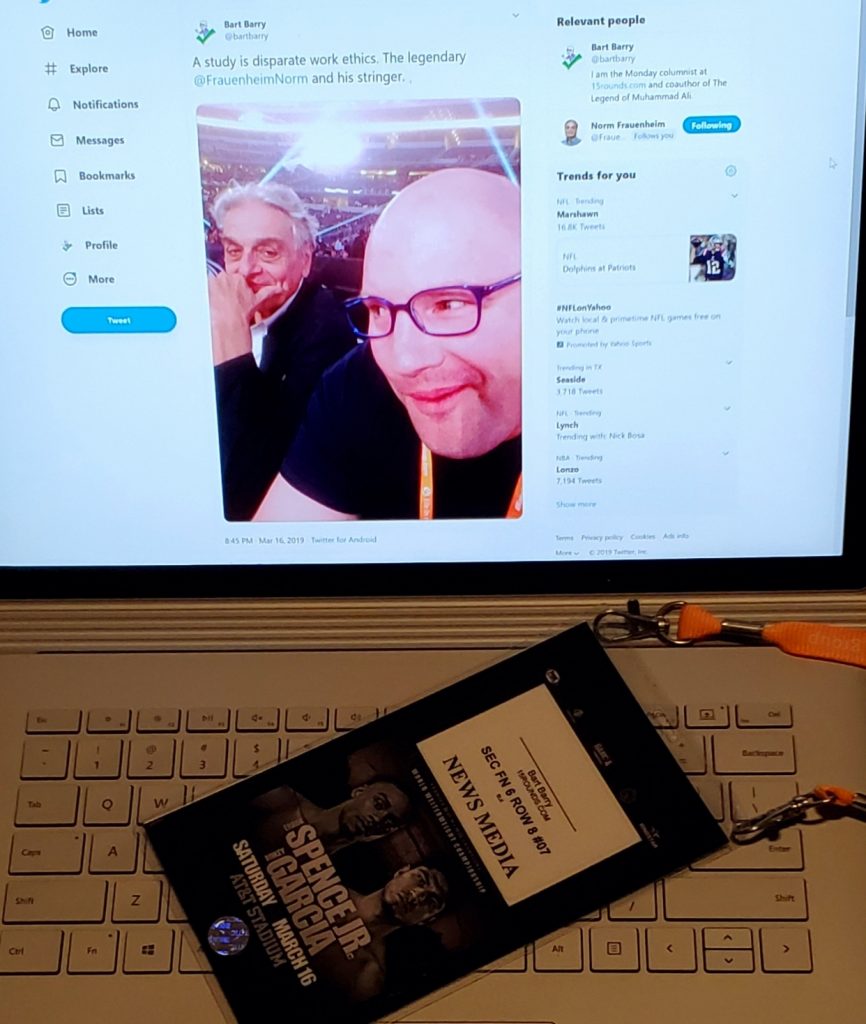

By Bart Barry-

He fumbles on his cell, trying to recall why he deleted the ESPN+ app, or if he did, or at least when he did if he did. No evidence on his cell ESPN ever lived there, but it must’ve back when because Google charged him for an account and so did Roku, and he’d meant to shut both off but was certain he’d left one on because getting the subscription deleted was engineered to be difficult, but why did he sign-up twice?

He returns to the PGA Championship’s official homepage, or an official-looking one anyway, who could tell or had the inclination to try, anymore, with the affiliate bullshit that felt porous and dumb in roaring times and now so much less in despairing ones. There’s a muddled suite of ways and venues for watching professional golf’s first major of 2020. Looks like ESPN+ is in indeed the pathway, especially if the comments below can be trusted, where middleaged men bemoan a pay service for the year’s first major championship.

Resigned to $6 a month less in his life he starts to reenable his ESPN account then recalls the headache that got him two accounts years ago and meanders in the other room where his television sits. Roku wants him to enable ESPN+ through a code it posts on a screen that directs him to use a mobile device to reenable his account. ESPN still has some account active, the emails from Disney come rushing in his inbox before even he gets fully reenabled, but there it is, the PGA Championship from San Francisco on a Friday afternoon looks glorious in high definition. Which must be why the commentators must ever crow about the courses’ beauty in every telecast for hours, another manifestation of that delicious new addition to America’s vernacular: Toxic positivity.

He solely wants to see Brooks Koepka defend his title, but the tariff for access to one excellent player is, as ever, documentaries, both cinematic and realtime, of Tiger Woods’ latest whatever. He checks the teetimes and sees Koepka scheduled to go in a half hour.

He mutes the television and replies to a work email. Morning’s interview for a new coaching position went well. The possibility of a maneuver, even a sideways one, makes the spirits lift and the workaday anxieties feel worth their suffering another week or two. Sees a tweet from City of San Antonio: average COVID new cases is back below 300-per-day for the first time in a month at least, and it makes him wonder if he got ahead of himself canceling a trip to Virginia for his father’s internment at Arlington.

Koepka should be teeing-off soon, and as the defending champ he should get the largest part of the – Tiger’s on the range. That invokes broetry recited by some halfassed method actor conjuring all that’s solemn in our national suffering and Tiger’s extraordinary selflessness and public service in playing golf to remind us what’s sacred in life. And what’s this?

They’re wrapping the ESPN+ broadcast and inviting viewers to ESPN. No. No!

He’s not had cable basic enough to have ESPN for at least six months and longer than that if he’d his druthers. He went years without a television and years after that without cable. Now he’s returned to PGA Championship’s official page to see if he can use his digital antenna to watch the telecast on CBS. Of course not. ESPN has weekday rights or something. He googles “cheapest way to watch ESPN” and sure enough Sling pops-up, Orange package.

He closes the browser on his cell and opens YouTube app and scrolls his history for a super slowmo video of Koepka’s swing:

John Salley on COVID-19, Chinese Meat Markets, Socialism, Dr. Sebi, Kobe, Jordan

Low Housing Inventory Will Change

NHL: Knockouts

Jon Favreau & Vince Vaughn 2001 interview

Spittin’ Chiclets Interviews Keith, Matthew, and Brady Tkachuk

Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain Interview (1997)

The Return Of The Muhle R41 by Kevy Shaves

Gentleman’s Nod Zaharoff – Wolf Whiskers Brush – Rex Ambassador

Hal Gill Told Us How Chugging A Beer Is The Only Way To Cheer Ryan Whitney Up

Brooks Koepka – Slow motion driver swing analysis

At last. Koepka lays the club off a little more at the top when you see his swing slowed down, that’s a bit unexpected, and it’s worth it to reenable Sling because Sling is the only online communications company that gets it. When someone wants a break from your service don’t harass him with surveys and promotions and reminder emails and affiliatemarketing horseshit. Let him be. Make reenabling his service a cinch. Nobody does this better than Sling, he knows, because he’s cancelled and reenabled his service at least four times and felt welcomed each return. His last confirmation email, in fact, told him Sling understood, in March, why he’d be canceling his service, what with all sports cancelled, and hoped only he’d consider a reunion if ever sports returned. Here he is.

Now he’s spending $46 or so in one day to see Koepka defend his title. Still cheaper than boxing, he thinks, long past balancing the money he saves on boxing, whether pay-per-views or subscription apps or travel, with what money he spends on shaving soaps and books about the science of complexity. Just one more click before Sling puts him on ESPN for the live telecast and Koepka’s gorgeous power fade. Premium channels – that’s right Sling offers those, too, else how did he cancel HBO a couple years ago (before AT&T began including free HBO with any purchase of Wally’s Songbird Super Buffet birdseed)? He remembers Showtime announced a new lineup of boxing a couple weeks ago, David Benavidez headlining.

“Fine,” he says to the empty room, “take my $10.”

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry