Reign of indiscriminate blows

By Bart Barry-

SAN ANTONIO – Outside the coffeeshop where this effort happens Nature is entirely mixed-up, leafless branches beside trees suddenly in bloom beside trees still shedding dead leaves. One week ago winter was a sleeting vengeance, a few days ago it was 90-degrees, today is more autumn than spring but neither Thursday’s summer nor Monday’s winter. It makes one wonder what dramatic changes home-construction philosophies will undergo necessarily in the next few decades, how inadequately traditional remedies and materials may serve.

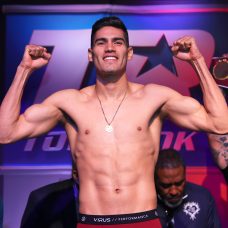

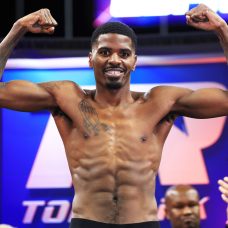

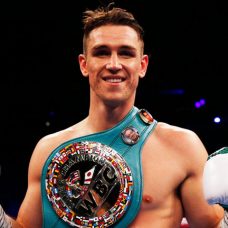

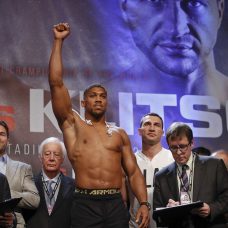

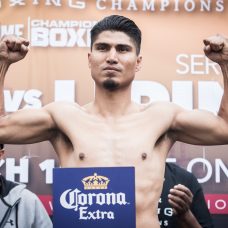

This was to be an essay about the difference between what Andrew Cancio did a couple Saturdays ago as the underdog in a world title fight and what Leo Santa Cruz did a late-replacement Saturday as a prohibitive favorite, and maybe it will be at some point accidentally, but there’s reporting and writing and homages of sorts, and this rarely be a space to come for reporting, so let this instead be a written homage in its way to what Santa Cruz did and the way he did it, busyness for its own sake, a ferocious pelting of partially aimed exertions that feel portentous in their moment but ultimately leaven’t a mark on their objects or audience.

Biomimicry, according to neuroscience (that wonderfully flexible science of whatever you wish it be – with every one of a trillion neurons representing the potential for a specialized field), increases human creativity, and so an observation about a dog on a hiking trail: He absolutely has a sense of himself, he is selfconscious enough to know “mine” – whatever else might territoriality be? – even as he hasn’t a grasp, really, of “yours” and at best a fleeting grasp of “not mine” much the way a human child grasps “my toy” years before “not my toy” years before “your toy”. And a dog is better for it since whichever comes first, selfconsciousness or memory, being unable to grasp not-mine or very much of the past-tense allows a creature to go through life with very few lamentations and nearly nothing akin to nostalgia. Most resentment probably reduces to “not mine anymore” and so even if biomimicry hasn’t made this effort any more creative it has limited finely its author’s chances at resentment – like: A talent for writing columns is not mine anymore – and if that doesn’t eliminate anxiety it certainly closes one door to it.

A brief reminder: Howsoever much we fetishize work ethic, when the real thing arrives, true and natural and genuine talent, it is a lightning bolt. That obvious, that different, that awestriking. It is a phenomenon so complete it causes us immediately to ask questions about luck, to pose riddles about what happened to a talent’s possessors born too soon or too late – what happened to the child born with Johann Sebastian Bach’s gift 5,000 years before the violin and harpsichord? what happens to the child born with Bobby Orr’s gift in Lima instead of Ontario? Maybe it’s all luck and has been and always will be, whether genes luckily arranged or luckily arranged genes lucky to come along when and where they did.

Unbeknownst to its readers, y’all, this column gets written after 3 1/2 hours of volunteering at a bus station on Sunday mornings with a nun-organized interfaith coalition whose ministry is easing the passage of just-released Central American asylum-seekers, predominantly women and very young children, as they make their ways to sponsors’ homes all round the country. Backpacks with blankets and coloringbooks and other sundries and bags of nonperishable foods get distributed, one to a family, sometimes 500 in a week, and itineraries get reviewed and maps gets drawn and on the occasion of stranded passengers shelter gets found, and it all adheres with remarkable consistency to a Karma Yoga principle something like: Work without expectation of reward. None of us is the caricature U.S. politics and its media coverage make us; the detention-facility contractors who escort the asylum-seekers to the bus station aren’t heartless or morally compromised, the Central Americans aren’t predatory or transactional but frightened and grateful, the busline is nothing like a psychopathic profitseeking entity, and the volunteers aren’t wholly without competing selfinterests. Every thing buzzes and improvises.

Sunday, though, a young mother with an infant child asked about her younger brother and where he might be, she had his bus ticket, and would they be bringing him to her, he was only five years-old – should she take her afternoon bus to Houston or wait for him at the station, and surely someone must know where he is, a five-year-old? Because the person who accompanied him from Guatemala was not his biological mother but his biological sister he had been sent to a different detention facility, and now his older sister stood in an unknown city, with a Spanish name at least, asking what she should do next.

You pass her on to a volunteer from a different, legal-counsel group, since she might have contacts at the detention facility, and you pass the griefcounseling role to a Mexican nun from a local monastery, and you walk it off by volunteering to get medicinal supplies from the basement of a local church. If fatigue makes cowards of every man so does powerlessness for the same reason, and there be naught so pathetic as impotent rage. With that as a disclaimer, then, take this in the spirit of its intention: The executive who enabled these policies may well be old enough to escape their consequences, but his abettors will not be – there will be trials for this someday, too much evidence has accrued since June and it evinces too much inhumanity, and so lets this act as but a tiny marker. When the apologists emerge, babbling about sovereignty this or patriotism that, calling every prosecution politically motivated and every sentence deeply unfair, know this: Justice is being served, finally if tardily.

Nothing unjust seems to happen in a boxing ring while the fighting happens. Fouls occur, yes, but no one gets to a level of televised combat without he knows how to suffer and avenge such things. There are refs who shade one way or the other, generally a-side, but they don’t get to where they are, either, without a thousand hours of practice. Our beloved sport’s injustices happen offcanvas. Judges, promoters, managers, so forth. The more decisive a man is in the act of fighting another the better his chances of going unrobbed by refs and judges, though, which is another reason to celebrate what Andrew Cancio did some Saturdays ago in California, when he beat his opponent to quitting and took the matter directly out of any hands but his own.

As one ages the more easily he finds it to celebrate individuals who manifest justice with their own fists than to catalog injustices. Or perhaps that is what laziness and cowardice catalogers would say it is.

Outside on the communal green of this revived and repurposed historic brewery a collective of acrobats or yogis perform balancing acts we once called cheerleading but now bedizen with spiritual elements, perhaps deservingly, and it’s the performative act of the whole thing that rankles. But no sooner does one reach for a metaphor about social media’s ills than he realizes human spirituality has often as not been a performative act, has it not, and, anyway, he’s too young, still, to be so curmudgeonly.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry