What the hell just happened in Oklahoma?

By Bart Barry-

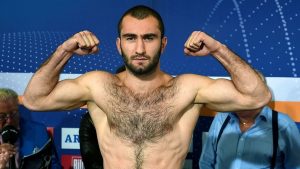

Friday at Buffalo Run Casino in Miami, Okla., in a match televised by ShoBox between Russian-Oklahoman super lightweight Ivan “The Beast” Baranchyk and Arizona’s Abel Ramos an unlikely thing happened: An inspired fight before an inspired crowd – folks donning Jason Voorhees hockeymasks to see The Beast ply his wares – with excellent refereeing and commentary.

An honest prizefight is what it was, was what it is; two guys whose records corresponded and whose styles meshed and whose officiating was proper and whose willingness to exchange was admirable. But thrice as admirable when pitted against their competitor spectacles on other locations round the cable spiral both Friday evening and most evenings these last two years. ShoBox used to do lots of this sort of thing and perhaps hasn’t stopped doing so but its parent network’s sequestration by an overleveraged manager returned home to a network that pays him after plethoras of failed gambits on networks he paid to broadcast his miserable mismatches made most aficionados move their Showtime subscription dollars to more essential products like sugary breakfast cereals, organic avocados or almond milk: Nobody took a stand and cancelled his Showtime subscription so much as he elected to deselect it when he remembered he still got billed for it, and his Showtime-dedicated funds went aimlessly back in the household budget.

Friday was a wondrous break from what PBC fare ruined Showtime, in other words, and a chance, too, to see a Russian fighter developed somewhere other than HBO, and development is exactly what one hopes will come for Baranchyk now that he knows his admirably mindless commitment to punches becomes a handicap when no one is there to stop his punches for him. Round 1 saw something an aficionado doesn’t see every day: a double lefthook lead throw in doublestep. Baranchyk leaped with a lefthook lead missed widely enough to land squarely enough to stutterstep then launched himself again. Where does one practice such a maneuver often enough to unveil it in a televised prizefight – on a line of heavybags?

The problem for Ramos, well, for both men but especially Ramos, was how unpunished went Baranchyk’s bad behavior; if you let an opponent hurl himself unabashedly in your direction and do not welt him for the offense, he’s going to keep on keeping on till he clips you. And clip you Baranchyk did in round 3, throwing fearlessly an overhand tornadomill right that clubbed Ramos into the deep ropes, from which Ramos energetically rose to drop Baranchyk with an even better lefthook counter, a favor returned by Baranchyk a few minutes later. By then the fight was even-to-favoring-Ramos but about to move quickly in its opposite direction as Ramos’ one glaring flaw became exploited tirelessly by Baranchyk.

Ramos floats his chin slightly at ringcenter and muchly in retreat. In the match’s opening moments Ramos looked a touch too elegant in his long and relaxed frame though one couldn’t quite name it till Baranchyk made him step backwards, and up came the chin. It’s a slight but real flaw that, worse still, is really deep, and here’s why: The plane on which Ramos now rests his eyes in a fight is different for his having learned to look out the center of his eyes than if he’d learned to look out their tops, and very much of his natural tempo and balance would now be disrupted by the claustrophobia of lowering his chin another inch to the top of his chest, where Baranchyk’s chin gets plugged soon as his hands come up.

Fathers, teach your sons to tuck their chins the same day, first day, you set their stances.

It’s very possible Ramos’ floating chin was no more apparent to Baranchyk than it has been to Ramos’ handlers but the comparative ease with which Baranchyk made Ramos take backwards steps was not lost for an instant on the Russian. Once Ramos was getting moved back the forced retreat generally continued till the ropes, and once the men were pitched on the ropes Baranchyk was an inevitable favorite because, while Ramos might’ve been able to infight slightly better than other tall folk, he was doing the one thing Baranchyk wanted to do, which bears reiteration: Had Ramos stood at ringcenter and strafejabbed Baranchyk the Russian’s naked leads would’ve grown more desperately emphatic, but by fighting chest-to-chest as Ramos did he gave Baranchyk the one chance Baranchyk’s tempo and technique and conditioning are shaped to exploit.

Ramos might have prevailed fighting Baranchyk’s fight – à la Alexis Arguello – and he would have certainly prevailed fighting from outside while Baranchyk could not have prevailed from the outside, so it made no sense for Ramos not to fight there. Some of Ramos’ infighting was pride but much of that pride was a reaction to feeling the scratch of shiny wrappingtape on his shoulderbacks and knowing if he didn’t fire back the Russian’d deposit him on the scorer’s table.

Which moves to a final point of applause for Friday’s prizefight, and it goes to the referee: Oklahoman Gary Ritter did a fine job of remaining practically invisible in a scrappy contest whose delicate balance would have been ruined by an official more officious. Did Ritter’s relaxed policing favor the adopted Oklahoma volumepuncher from Russia? Surely it did a little but it also gave Abel Ramos valuable experience and entertained a partisan Miam-uh crowd and a nonpartisan Showtime viewership. More of that, please!

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry