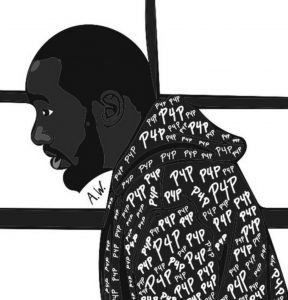

Parse and Punish: On Terence Crawford

By Jimmy Tobin-

It’s the smile, the mischief in it. There’s self-satisfaction there too, irrepressible, mocking. And something more sinister at work. A pleasure in cruelty perhaps? Even in the theatrical? A relish in the power to shape a moment according to one’s will maybe? To create a unity of the rapt thousands looking on? Yes, that’s certainly part of it. It is a conscious display, this smile, one understood by all—the crowd, the judges, the opponent—to signal one thing: that a beating is at hand.

***

Terence Crawford’s smile, like so much of the fighter, is charming in its menace. And like so much of the Omaha, Nebraska fighter, it was on display at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas, Saturday night where Crawford announced his arrival at welterweight by butchering Australian Jeff Horn in nine rounds. Crawford may find his ambition thwarted in his new division but if there was one message to take from watching him parse and punish Horn it was this: Crawford is not the welterweight who should be worried. And he is not.

That smile appeared in the third round when it became clear that all of Horn’s early success had been little more than the modest price of calculation, an allowance in the name of salting the meat. By the third round, Crawford found his range, appraised Horn’s rhythm, his power, his strength, and knew—like seemingly everyone save for Horn’s trainer, Glenn Rushton—that competition henceforth would bleed from the bout. Say what you will of Horn the fighter, of his disputed victory over Manny Pacquiao last year, he goes boisterously to his fate against everyone in the division not named Errol Spence. That may be an indictment of a division that even three years ago was considered as good as any in boxing; it may be a referendum on the merit of the fighters who once justified that esteem. Either way, in butchering Horn Crawford reminded us what divisional rankings cannot: that the distance between fighters on a list is anything but uniform.

Crawford was smiling in the ninth too, as he ripped double-hooks into Horn’s body, savoring the buckle and bend, the pain they produced. He was smiling again seconds later as referee Robert Byrd spared Horn, too tough for his health, the type of lingering abuse that ages fighters overnight.

Because Crawford is as good a finisher as you will find: patient, accurate, creative. Roman Gonzalez, also flawless in the pursuit of destruction, expressed a genuine appreciation for the person absorbing his punches, and that tangible intimacy kept his abuse sporting. But Crawford? Crawford is mean, irresistibly so. When he sets upon an opponent he isn’t exorcising demons, violence does not appear cathartic for him. No, Crawford is taxing opponents for their insolence, showing too those ungloved and uninteresting talking heads what he thinks of their criticisms. (Indeed he said as much when asked about his bullying of Horn, ostensibly saying that the people who questioned his strength needed to be reminded whose opinion the fighter actually credits.)

There is something Mayweather-like about Crawford (now the best American fighter in the world), in the way he first studies then disarms his opponents. But unlike the welterweight version of Mayweather, Crawford goes beyond merely establishing dominance, he imperils himself at his opponent’s expense. You do not hang around with “Bud”: if he thinks he can end you your daylights depend on convincing him otherwise. That may change at welterweight, where opponents are more stubbornly absorbent, but the strength and power Crawford displayed Saturday say otherwise.

There are some who will temper their enthusiasm for Crawford, noting that Horn was but one more hapless opponent heaped on the pile used to elevate Crawford’s accolades beyond his accomplishments. There is some truth to that, particularly given the model for developing fighters that flourished recently on HBO, where greatness was bestowed at the outset and opponents approved to preserve it. And really, did anyone save for Viktor Postol’s staunchest supporters expect Crawford to lose any of his thirty-three fights? There is something to be said for how you win, however, and in fighting the only opponents available to him Crawford has left little doubt of his excellence. Besides, any further fights below welterweight would only delay seeing Crawford challenged, which is precisely what those who have yet to embrace him need to see.

It would be interesting to hear who those same reluctant admirers would prefer Crawford face next. Because if the goal is to have Crawford prove himself there is but one name on that list. And while it might be interesting to watch Crawford chop Shawn Porter up, or hang the first stoppage loss on Danny Garcia, or show Keith Thurman the difference between a person who fights for a living and a fighter, the outcome of all of those fights would only move the bar on Crawford.

No, the fight for Crawford is with Errol Spence, and the time for that fight is now. No other opponent brings the same challenge, and scant others will teach us anything we don’t already know.

You can hear it already: “But the promotional issues, network alliances! Mandatory defenses! The fight could be BIGGER!” Stop. No one drawn to a bloodsport for the blood cares about the obstacles to this fight happening—those obstacles, however cutely worded, are only excuses long employed by promoters to deprive the public of what it wants. So fuck all that.

One imagines Spence when he looks at Crawford, sees a former lightweight coming for his crown. And Crawford, when he thinks of Spence, the strapping southpaw with the bricks in his fists? Don’t kid yourself—he probably smiles.

Sergey “Krusher” Kovalev got the opportunity he wanted Saturday night at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Las Vegas. Seething from what he believed to be a bogus decision loss to Andre “Son of God” Ward in November, enraged by Ward’s conduct in a dead promotion leading up to their rematch, Kovalev swore to deliver a display of ultra-violence that would permanently remove Ward from the sport. In the eighth round, without a whiff of protest, Kovalev let referee Tony Weeks save him from that opportunity.

Sergey “Krusher” Kovalev got the opportunity he wanted Saturday night at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Las Vegas. Seething from what he believed to be a bogus decision loss to Andre “Son of God” Ward in November, enraged by Ward’s conduct in a dead promotion leading up to their rematch, Kovalev swore to deliver a display of ultra-violence that would permanently remove Ward from the sport. In the eighth round, without a whiff of protest, Kovalev let referee Tony Weeks save him from that opportunity.