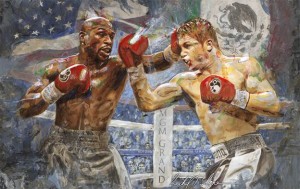

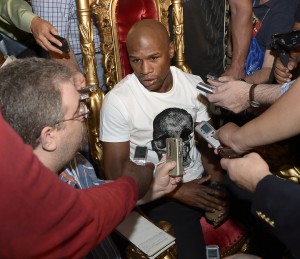

LAS VEGAS – It wasn’t exactly easy money. More like seed money.

Floyd Mayweather Jr. planted what he hopes will blossom into five

more Showtime fights for $250 million with a decision more one-sided

than unanimous Saturday night over Robert Guerrero in a welterweight

bout at the MGM Grand.

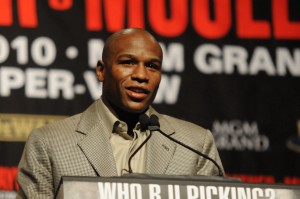

“Five more to go,’’ Mayweather (44-0, 26 KOs) said. “Let’s do it.’’

Can he? That answer was the key to Mayweather’s first fight since

his release from jail late last summer and his first bout since

beating Miguel Cotto a year ago.

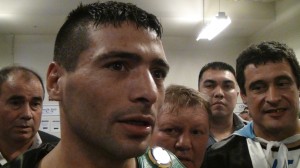

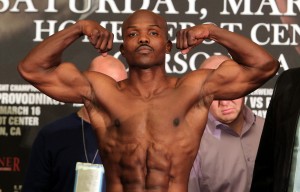

Guerrero (31-2-1, 18 KOs) was there, perhaps, because he is as

tough as he was overmatched. His lack of speed and limited athleticism

made a Mayweather victory likely. It was the same on all three cards.

Judges Julie Lederman, Jerry Roth and Duane Ford scored it 117-111,

each for Mayweather.

On the 15 Rounds card, Mayweather was a 120-109 winner with

Guerrero failing to win a round. 15 Rounds scored the first round

even. Guerrero appeared to be winning the second, but that proved to

be the beginning of the inevitable when Mayweather stole the round by

landing the first right hand in what turned into avalanche of rights.

Guerrero wound up bloodied above one eye. The ringside physician

looked at the eye after the eighth. But the doctor decided that

Guerrero could continue.

“He was hard to hit,’’ Geurrero said. “But I’ll be back. Maybe

back for a rematch.’’

Guerrero was hurt, yet upright. In hindsight, that’s why he was

picked to be Mayweather’s first opponent in the Showtime deal. Every

new vehicle needs a test drive. Mayweather got the full, 12-round

drive, shaking off some initial stiffness and establishing some

familiar fluidity later.

There were also no hitches in the reunion with his dad, Floyd

Mayweather Sr., as his trainer. Roger Mayweather, his uncle and his

lead trainer for years, wasn’t in the corner, although he was in

middleweight J’Leon Love’s corner for a controversial victory on the

undercard.

“My father provided defense,’’ Mayweather Jr. said. “The less you

get hit, the longer you last.’’

Durability is the key if Mayweather hopes to collect the $250

million that is there if he fights five more times over the next 30

months. Even in the Guerrero fight, he might have suffered a

problematic injury. He complained of pain in his right hand, which he

said he hurt midway through the bout.

“I feel bad I didn’t give the fans a knockout,’’ said Mayweather,

who was guaranteed $32 million, more than 10 times Guerrero’s $3

million, according to contracts filed with the Nevada State Athletic

Commission. “I was looking for it. I hurt my right hand.’’

It wasn’t known late Saturday whether the hand was hurt bad enough

to prevent him from fighting in September.

“I plan to fight in September, yes,’’ Mayweather said a couple

hours after defeating Guerrero.

Even if healthy, however, Mayweather’s history indicates that five

more fights over the term of the deal are unlikely. He hasn’t fought

twice within 12 months since 2007.

Canelo Alvarez, the popular Mexican red-head, has called out

Mayweather repeatedly. After beating Austin Trout in San Antonio,

Alvarez again said he wanted to fight Mayweather. For Showtime, a deal

without Canelo-Mayweather would seem to be a bad one. Showtime, Golden

Boy Promotions, Mayweather and Canelo have 30 months to get it done.

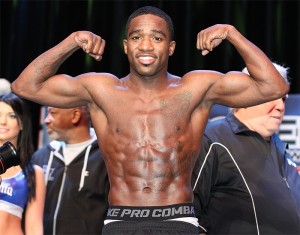

If there is a Mayweather fight in September without Alvarez, there

are other possibilities. Danny Garcia, the current junior-welterweight

champion, was mentioned in Saturday night’s aftermath. Welterweight

Devon Alexander was another possibility.

Golden Boy Promotions CEO Richard Schaefer talked about somebody special.

A “red-headed” somebody, he said.

Schaefer didn’t have to say who.

After what happened Saturday night, talk about Mayweather-Alvarez

took on a momentum all its own.

Best of the Undercard

It was friendly fire, the toughest kind of all.

But a contract between longtime pals and sometime sparring

partners, Abner Mares and Daniel Ponce De Leon, had to be fulfilled.

It was.

In full.

Mares (26-0-1, 14 KOs) made sure of it with a brilliant display of

versatility and surprising power for two knockdowns in a ninth round

TKO of Ponce De Leon (44-5, 35 KOs) for the World Boxing Council’s

featherweight title.

“He’s my friend,’’ said Mares, whose friendship with Ponce De Leon

includes the same manager, Frank Espinoza. “I wanted him to stay down,

especially after I dropped him the second time. You just don’t want to

keep hitting a friend.’’

There was some mild controversy over whether Mares should have

been allowed to. After dropping Ponce De Leon with a right in the

ninth, Mares pursued and caught him along the ropes with succession of

blows. At 2:20 of the ninth, referee had seen enough. Jay Nady ended

it, despite Ponce De Leon’s pleas for more.

“I don’t feel the fight should have been stopped,’’ said Ponce De

Leon, who also said he wants a rematch.

Friendship’s perks might get him one, although that would still

leave him with an impossible task. In Mares’ first fight at 126

pounds, he knocked down Ponce De Leon with a left in the second and a

right in the ninth.

“I think I confused him,’’ said Mares, who dedicated the victory to

his father. His dad suffered a stroke nearly a month ago.

The Rest

· A move up in weight embellished Leo Santa Cruz’ emerging

status as perhaps the best fighter in the 118-to-126-pound range with

an overwhelming stoppage of ex-flyweight champ Alexander Munoz of

Venezuela in a junior-feather bout. Santa Cruz, of Los Angeles,

dedicated his victory to an ailing brother. “He’s fighting for his

life,’’ Santa Cruz (24-0-1, 14 KOs) said. He fought for him, knocking

down Munoz (36-5, 28 KOs) in the third, rocking him with head-snapping

punches in the fourth and finishing him off with a right-left

combination at 1:05 of the fifth. Santa Cruz landed an astonishing

219 punches before five rounds were complete, according to CompuBox.

Santa Cruz might be next for Mares, according to Golden Boy Promotions

CEO Richard Schaefer.

· Las Vegas middleweight J’Leon Love (16-0, 8 KOs) got no love

in getting a split decision, booed loudly and often, over Garbriel

Rosado (21-7, 13 KOs), who lost despite scoring a knockdown in the

sixth round with a right. “It is what it is,’’ Love, a Mayweather

Promotions prospect, said after the 10-round victory over Rosado, a

Philadelphia fighter who sat on top of the ropes in his corner and

shook his head as if to say it was lousy.

· Las Vegas super-middleweight Ronald Gavril (4-0, 1 KO) closed

the non-televised portion of the pay-per-view card with a sweeping

right hook that appeared to leave Roberto Yong (5-7-2, 4 KOs) of

Phoenix defenseless and without a chance. Referee Russell Mora

stopped, making Gavril a TKO winner at 2:12 of the third round.

· Super-middleweight Luis Arias (5-0, 3 KOs), a Cuban

super-middleweight now living in Las Vegas, relied on a solid right

to survive some rocky moments and repeated left hands from DonYil

Livingston (8-3-1, 4 KOs) of Palmdale, Calif., for a six-round victory

by majority decision.

· Las Vegas light heavyweight Badou Jack (14-0, 10 KOs) of

Mayweather Promotions landed a right-handed body punch that put

Michael Gbenga (13-8, 3 KOs) to one knee in the third. Gbenga of

Silver Springs, Md., complained that the punch was a low blow. Video

said otherwise. Jack stayed unbeaten, winning a third-round TKO.

· Las Vegas super-middleweight Lanell Bellows (4-0-1, 4 KOs)

won a fourth-round stoppage over Matthew Garretson (2-1, 1 KO) of

Charleston, WV.