By Bart Barry-

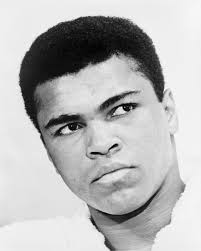

Muhammad Ali died Friday evening at the age of 74. His death was long anticipated by those who follow our sport and know the ruinous effect it visits on each of its professional practitioners. Round the world Saturday persons instantly and for the most part sincerely began to mourn a man most had not thought about in decades, reliably imparting how much larger Ali was than his and our sport.

The happiest benefit of writing for a site like this, a boutique affair designed for aficionados, is the relief that washes over a writer when he remembers on days like these he does not need to put the accomplishments of a prizefighter in the larger context of others’ fantasies. If he doesn’t have a champion’s record memorized, quite, he has access to memories enough to write confidently about the only interest a reader should bring to a site like this. It isn’t liberating in the wildeyed gamboling-through-a-daisy-patch way we lately understand the word but it’s sufficiently liberating to make an exercise futile as this one doable.

This won’t be a piece that cherrypicks anecdotes showing how well the deceased represented my specific and fairly narrow worldviews, a selfhelp epic stiffened by another man’s violence, and it won’t be an exhaustive and autobiographical drumroll either; my earliest recollection of Ali was his being a sad foil to Larry Holmes, and therefore no amount of YouTube immersion makes Ali’s effect on me deep or enduring as those taken by champions of my youth and adolescence like Marvelous Marvin Hagler and Mike Tyson.

If you’re here for a definitive obituary you’re going to be disappointed. What follows is better read as an honest attempt at an obligatory act.

It begins with violence. In the press to canonize Ali his impulse to violence has been scoured till bleached. He danced and floated with a gorgeous face and an enchanting physique and golden glow because he was a pacifistic poet who would shape a generation and show a worldful of people their better selves. No, not really, but the cardboard saint must be propped high – the better to reflect us for us.

Doubt not the importance of Ali’s reflective surface on the legacy so many now celebrate. As Parkinson’s (disease, syndrome, etc.) made a marble facade of his once-expressive and often-offensive countenance Ali’s capacity for challenging others’ ideals to a point of repugnance and rage congealed to a face tailored for beloving. Ali went along with it because he did love others’ adoration and because he also loved money and because, ultimately, how much choice did he have as he watched in amusement an entire country following a pattern of attraction seen in bars round the world every night: Repulsion to curiosity to fixation?

Ali was an original who inadvertently provided future marketing masterminds a template they ably applied to Tiger Woods then Barack Obama, neither of whom was possible before Muhammad Ali.

Back to violence. Look closely at how Ali set his mouth when he threw righthands – hurting punches thrown with every intention of bringing pain or unconsciousness or both to the men across from him. Don’t dismiss this as an anomaly either; Ali had athleticism and charisma enough to make his living quite a few ways other than hurting others but he hurt others for a living because he was great at it in a way we rightly call historic. That is an aesthetic judgment, not a moral one; it is a reminder Ali’s ascent from Olympic gold medalist to heavyweight champion of the world relied necessarily on his conversion from an athlete who boxed for points to a fighter who hurt other men, and he didn’t do it reluctantly.

Look at his mouth when he threw right hands and look at his eyes when he took other men’s consciousness. Ali was all fighter. Since that is not palatable to many target demographics today we are told how much larger than his profession Ali was by people who for the most part do not understand Ali’s profession and wish to assert the greatness of their times by making the greatest of their times relatable to absolutely everyone.

This collision happened a lot in the obituaries that happened in the hours after Ali’s death, obituaries many sportswriters began composing a decade ago. What to say about a great man when one’s peers in radio and television use the word “great” to describe a hundred things weekly? Ultimately, if you have any craft at all you revert to understatement and hope for the best, as many of our craft’s best craftsmen did. Otherwise you convict language itself of inadequacy then use a sprinkler-system approach, dashing from accomplishment to accomplishment in the hopes some rule of sheer yardage will capture the totality of the man.

Inspiration is ephemeral but sexy to claim from another. Of those millions who today claim Ali as the source of their inspiration, it is proper to ask: Inspiration to do what?

Social media answers the question in most cases: Try to become famous.

Those claiming to be inspired by Ali to do other things are persistently unreliable with one exception: Fighters. There’s some mention of Ali in every boxing gym across the land (at our gym, curiously, there’s a black-on-gold mural of Ali with a quote attributed to him that goes: “Champions are not made in the gym”) and Ali surely inspired a large number of fighters in the generation following his to don gloves and dance, hands lowered, looking pretty. And most every one of those guys got his clock cleaned in month one and retired instantly thereafter.

To the cultural critics goes the task of naming, numbering and coloring-in every way the man was larger than his profession. To aficionados it need go no further than this: Muhammad Ali was the very best fighter in his division’s very best era.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry