By Bart Barry-

Editor’s note: For part 17, please click here

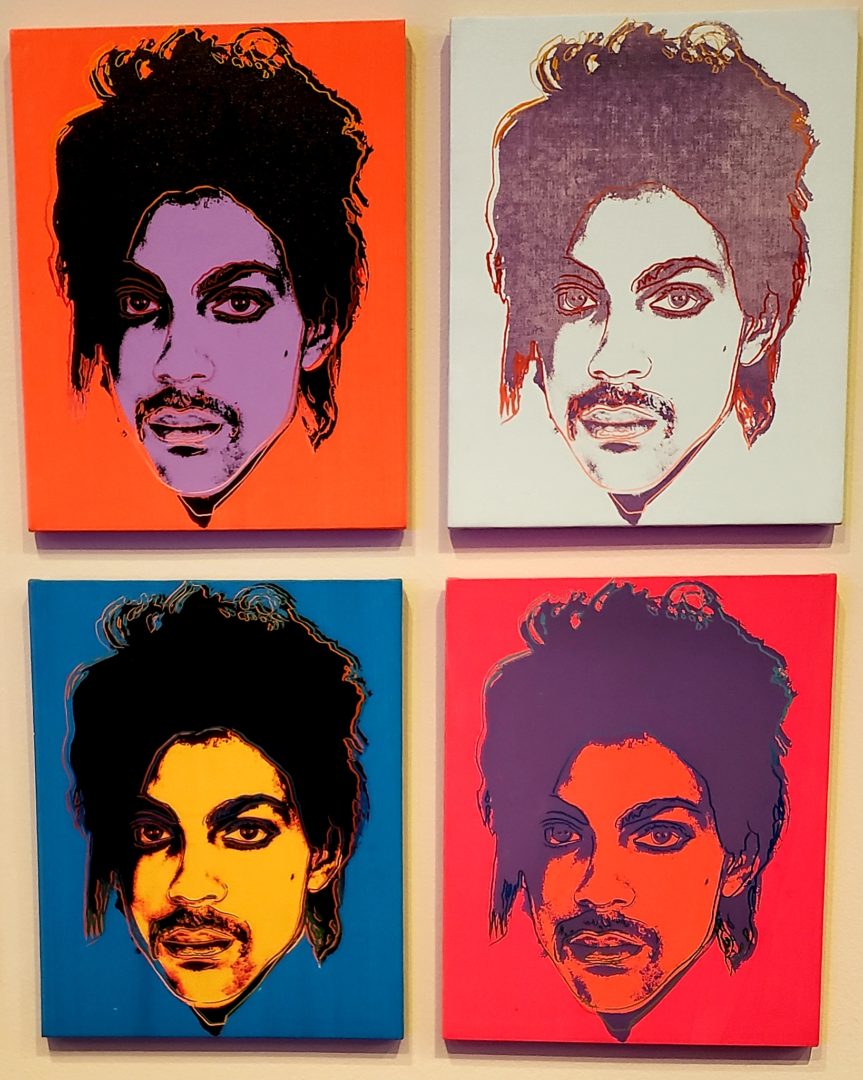

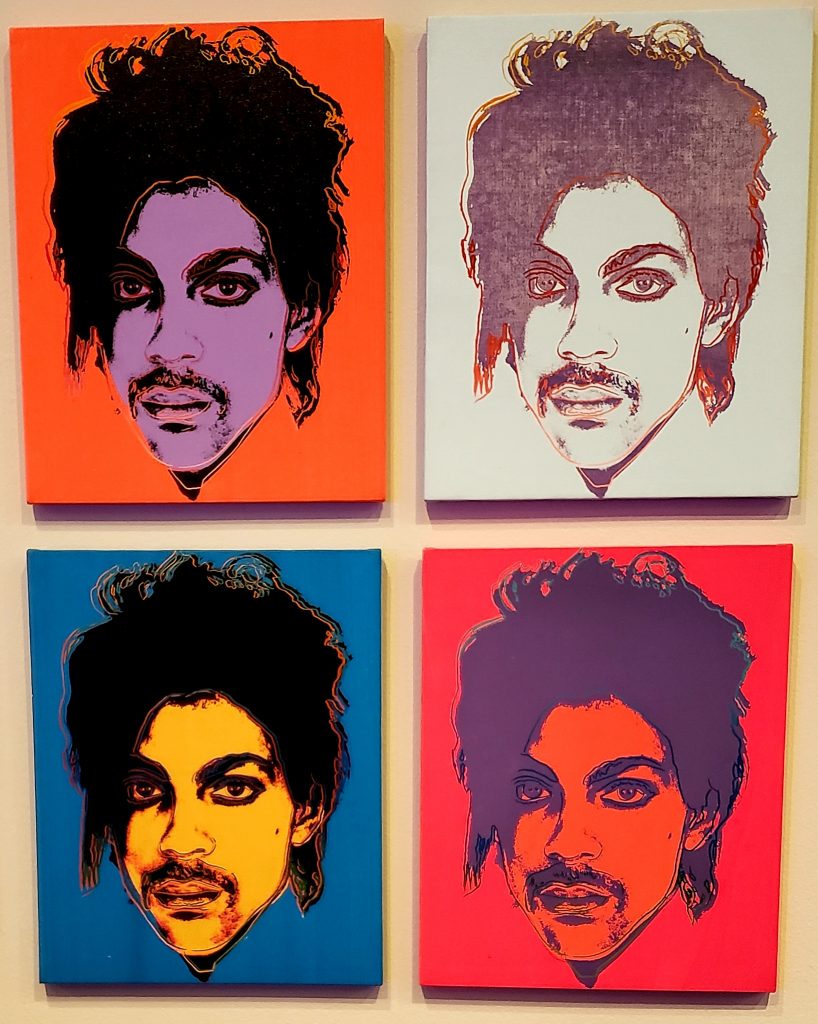

SAN ANTONIO – This city’s McNay Art Museum, which has figured heavily (for an art museum) in this ostensibly-about-boxing column, since 2010, recently opened an exhibition, Andy Warhol: Portraits, that appears to have no tie-in whatever to our beloved sport. I revisited the exhibition a few hours before writing this, unable to imagine a suitable subject, and sat so long at a lobby table afterwards a friendly security guard came over to tell me I looked tired. Let that temper what you expect of this.

Nearly a decade ago The McNay had a different Warhol exhibition that opened round about the time “Son of the Legend” Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. put the wood to “Irish” John Duddy in Alamodome, in what would be Duddy’s final prizefight. The editor of a boxing magazine asked me to pitch him a unique idea for a story – “anything out of the ordinary” – and I complied with an idea about this Warhol exhibition, a visual dissection of Warhol’s fascination with celebrity and its effect, being open in the same city at the same time as boxing’s greatest beneficiary of celebrity. The pitch went nowhere, a destination shared by the story I wrote instead for the magazine, and I made a column of the idea.

(Actually, a quick search through the archives reveals barely half of what’s above is accurate; “Andy Warhol: Fame and Misfortune” opened in February 2012, not June 2010, and since by then Chavez Jr. had beaten Duddy and Sebastian Zbik and Peter Manfredo, perhaps a story attributing the whole of Chavez’s fortune to name recognition wasn’t the crackerjack idea memory recalls.)

Out of the parenthetical but influenced by it: Memory is many parts imagination, something confirmed by most adult accounts of childhood that begin “I see myself . . .” as if that’s what children do when, say, riding a bike – look at themselves, instead of their front tire or whatever terrain it touches.

If Warhol never directly addressed memory’s inaccuracy, and perhaps he did somewhere, prolific as he was, he understood part of the appeal of his portraits to their subjects lay in a capacity for overwriting memories. Warhol was a favorite portraitist of aging celebrities because his minimalist approach to depicting facial skin removed wrinkles and most blemishes (except for his Dolly Parton portraits, which are better than the Marilyn Monroe portraits precisely because Parton’s face had more imperfections). Warhol very much made art for life to imitate and prophesied our contemporary socialmedia obsession in any of his dozens of commentaries about Americans and fame.

Floyd Mayweather would look good in a Warhol portrait, methinks. I happened on a Fox Sports promotional movie about Manny Pacquiao last week by accident and tried to see Mayweather through his fans and commentators’ eyes, being removed as we are now from the relevance of Mayweather’s schtick. What I looked for was elegance; what little I recall of his victory over Pacquiao was Pacquaio’s unwillingness to throw punches and subsequent inability to strike Mayweather, our defensive wizard. But what I saw instead of elegance was skittishness. Not during or after Mayweather got hit but when the prospect of his getting hit happened: Confident-to-flinching-to-confident-to-flinchyflinching. It was not elegant.

Of course this was a movie to sell us Pacquiao’s upcoming tilt with Keith Thurman, and it behooves nobody at Fox to concede Pacquiao is diminished from the man who got whitewashed by Mayweather, a man who was fractionally potent as the one who dashed through Barrera and Morales and Marquez. Still. In hyperdefinition, Mayweather’s squinchyfaced pullback looks nigh bitchy.

Warhol would remove that. If Warhol was not quite enamored of money as Mayweather claims to be, he was doubly enamored of money’s effect, and Mayweather’s selfstyled fixation on money might’ve enchanted Warhol with a question like: If a man who is by no means the world’s best at making money allowed the last 1/3 of his career to be consumed by making money, a man who was the world’s best at his actual craft, does that make money omnipotent or the man cynical?

This is why I looked tired in the lobby. A different range of thoughts happened on the short, slow drive from The McNay to The Pearl, where this column got wrote: Is the racing line elegant? is the racing line what Henri Matisse was after? is Matisse better than Warhol, for eliminating pathways to imitation, or is Warhol better, for spawning generations of imitators? how much should even a column such as this be dedicated to a concept, the racing line, you understand at best partially?

The racing line is a way automobiles may go fastest round curves. It’s not the shortest distance, as that would be the inside line, and it’s not a good way to go at a constant speed. Rather, it’s effectively the straightest way to go round a halfcircle – start wide, cut the apex, end wide – and by being the straightest line it is the route that allows the earliest moment of maximum acceleration. If you regularly take the racing line against fellow motorists on your local freeway you will pass most of them so long as you do not use cruise control (which renders the racing line counterproductive).

The racing line is almost elegant the way Warhol is almost elegant. Neither the racing line nor Warhol is elegant as a Matisse line; the racing line and Warhol do something worth doing more quickly than other approaches. The racing line kept through a full circuit is nearer Matisse than Warhol came; Warhol was the racing line through a single curve, maybe two. The Matisse line, though, is the racing line taken through an unknown circuit drawn but a moment before.

Tire, tiring, tired.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry